- Advertising

- Find the Magazine

- Good Jibes Podcast

- Boat In Dining

- Sailboat Charters

- Business News

- Working Waterfront

- Youth Sailing

- General Sailing

- Repair & Maintenance

Raising the Mast of a Small Sailboat with The Resourceful Sailor — The Solo Version

It’s been a while since we’ve heard from The Resourceful Sailor. Since he lowered the mast on his boat Sampaguita last June, he’s been busy taking care of several boat projects. Now he’s back on deck and has sent us this detailed report on raising the mast.

What goes down must go up? After a rig refit, the mast of Sampaguita , a Pacific Seacraft Flicka 20, was ready to be raised. Still in her Port Townsend slip, the process was, generally, the opposite of lowering, presented in ‘Lectronic Latitude on June 16, 2021 — Lowering the Mast on a Small Sailboat with The Resourceful Sailor .

It required the same bridle setup. The boom, again, would act as a gin pole to gain the proper angle for leverage. The mainsheet block and tackle would do the heavy lifting. Rather than write the same thing again, I will focus on the differences between the two procedures and provide some previously left-out insights. In doing this, I will presume that you have read or will review the installment mentioned above.

For raising, only the cap shrouds and the headstay needed to be attached to their respective chainplates. Out of respect for Murphy’s Law, the other wires were secured tightly to the mast to mitigate their inclination to get snagged. Snagged wires like to kink, and whether new or old, it is unsatisfying, not to mention detrimental to their longevity and strength. The turnbuckles were wrapped in rags and secured to the mast, preventing them from scratching and banging into anything (everything.)

The bridle setup was more challenging to organize with the rig down than up. Since I had new wires, I needed to re-seize the stainless steel rings to the cap shrouds. It required holding up the wire to determine the proper pivot points with the mast. Then the opposing force lines to the lower stay chainplates were added, conceptualizing the rigid triangle necessary to maintain the pivot points. With the rig up, it is easier to build and see this. But down, it is a floppy mess. Then, a line was attached to each ring, ready to lead to a bail on the boom. A block and tackle served nicely for this on one side for ease of adjustment. These guylines will provide the opposing forces to keep the boom centered.

After that, I moved the mast to the tabernacle and pinned its base in the ready position. A final review of the halyard and wire leads and spreader orientations was done. A reminder: Always be on the lookout for snagging wires and lines whenever you move the mast.

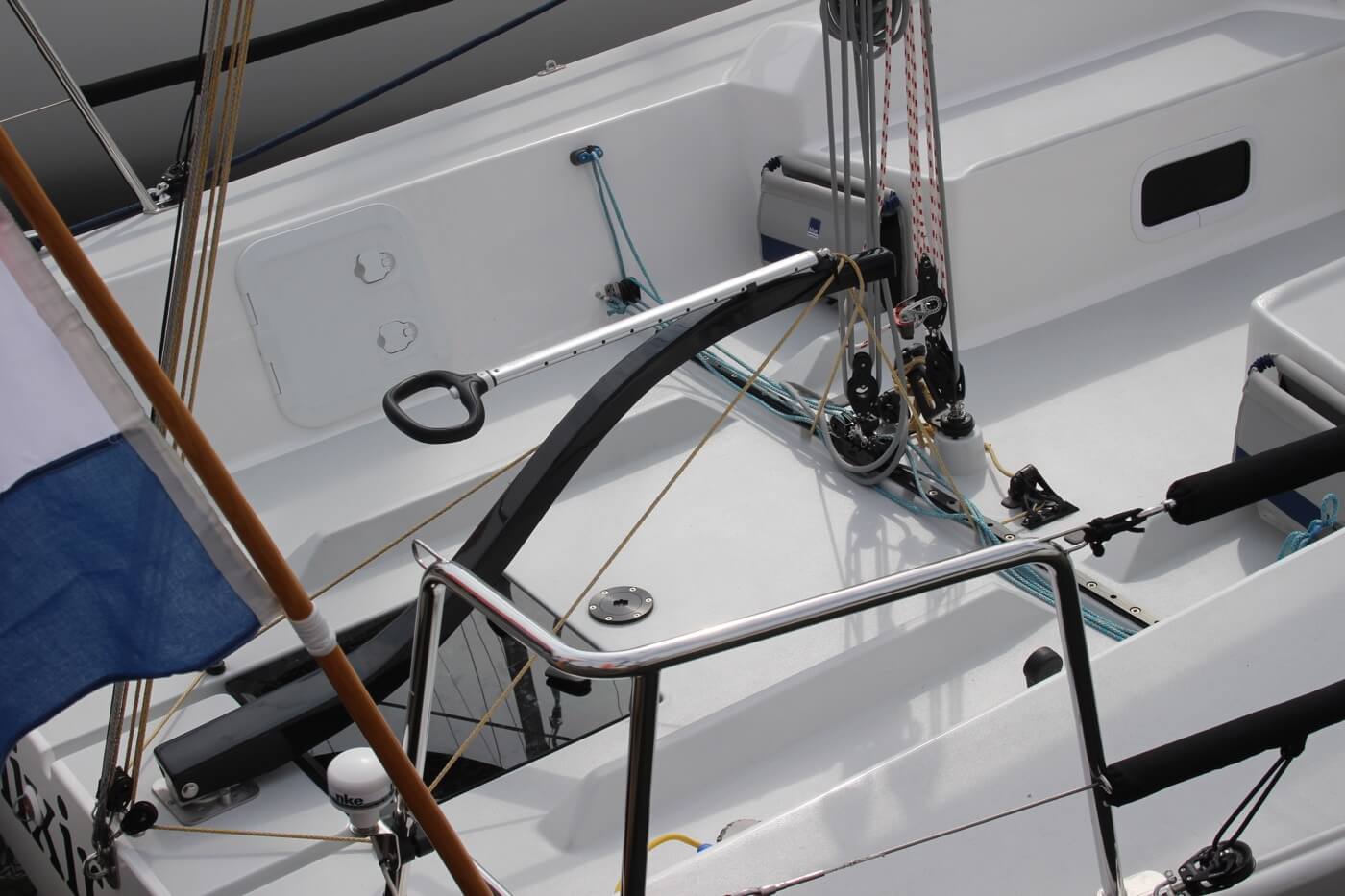

The boom, as a gin pole, could then be added. When lowering, it was already in position and there was only the matter of attaching the bridle lines. However, with the mast down, the boom would be attached starting in a vertical position, which involved some boat yoga. I shackled the mainsheet and topping lift to its outer end. Lots of slack was fed into those lines, allowing for lifting it straight up. While holding it so, I pinned the mast end to the gooseneck. I picked up the previously-led guylines (the line and the block and tackle) and attached them to the boom bail. I tightened and adjusted the mainsheet, the topping lift, and the guylines until the boom was centered and vertical. The opposing forces held the gin pole in place.

With the correct bridle setup, the mast base in the tabernacle, and the gin pole in place, it was simply a matter of hoisting the mast. On a Flicka 20, the round bar traveler and the four-part mainsheet block and tackle are very accommodating to providing the mechanical advantage necessary for raising and lowering the mast. To a soloist, this advantage was indispensable. It took two hands and a bit of leaning to get it moving, but it became easier as it went higher. An eye was kept on the centerline alignment of the mast and boom, making sure the bridle prep was accurate, and watching that the wires did not snag.

The accompanying video shows the raising from a first-person view and solo. In contrast to lowering the mast, gravity is less of a friend, so the ascent is slower, with a bit more heave-ho. There is no shame in re-lowering the mast to adjust the bridle lines or sort out the wires. It is better to correct them early than to think something will be all right when it is not. Raising and lowering the mast is not rocket science, but 99% of the gig is proper preparation. If something goes wrong, it could be catastrophic, so double- and triple-check. It can be intimidating at first, but it is simple physics and simple tools at work. Remember, keep it safe and prudent, and have a blast.

This is so stressful to watch! I would have never had the courage to do it myself. As always, you have my respect and admiration. Well done!

Rusty, thanks for the kind words, and thanks for reading.

Joshua, Thank you for taking the time for so nicely relaying your experiences on single-hand stepping the mast on your Flicka. I am currently refining this design process for my own boat, and am thus interested in the finer details. My initial questions are two: First, concerning the method and material for seizing the bridle to the cap shrouds: As you state, a properly rigged bridle is key to making the process work. How did you analyze the adequacy of your seizing method and the loads that would be experienced?

Temporary seizing is a good place to start for me, but since I do this spring and fall every year, I have considered incorporating a more permanent nicropress and cable pigtail for the ring attachment (the loads there are not very high). A triangular plate in the top shroud with attachment points for the bridle connection points would be nicer, but more expensive to implement. Either way, it is probably prudent to use a temporary seizing first, to demonstrate dimensional functionality prior to a permanent solution. Second, I am sure you release the cap shrouds to allow the bridle arrangement some up/down movement as a result of the mast butt movement in the tabernacle during stepping. Somehow I must have missed that. Once upon a time I tried raising the mast with very slack uppers (guessing at what was needed instead of graphical analysis or calculations) instead of the bridle approach (all else was like your scenario). Because the slack was inadequate and no bridle, I managed to bend my boom out of alignment. :o(. A good machine shop worked that out. As long as the mast remains vertical through the lift, there isn’t much load on that ring connection, but its job is keeping the mast in a vertical/perpendicular orientation through the lift. But if some kind of unforeseen incident would create shock loading on the seized ring, (say even 2 pounds of lateral movement (force at the truck) that would correlate to about 56 foot-pounds of moment (engineering statics) applied at the ring due to the long lever arm of the mast. If it were 5 pounds force perpendicular at the top of the mast, it would correlate to up to 140 foot pounds. In my view, a shock load of 5 pounds or maybe more, isn’t an unlikely scenario, considering Murphy. I can’t think of a way to analyze the strength of the seizing, and prayer does not work for me. So, how did you analyze the adequacy of your seizing method and what did you use? Wire? In my case, I have been stepping my mast at least annually, on my Lancer 25 for more than 35 years. I usually do it on the hard, or in the water if launching was via travel lift or something else that dictated the mast needed to be down when launched. But in at least one case, years ago, while sailing near Cowichan Bay at Vancouver Island, the jib wire jumped the sheave (a result of rough water and a slack line while dousing the jib) at the truck, and jammed along-side of the sheave when I tried to pull the sail down. I wasn’t sure of the problem at the time, but the sail definitely was not coming down, so I wrapped the jib halyard around the forestay to try to contain the partially-filled sail and considered my options. Luckily, upon checking my depth sounder, and found some shallow 30’ water (unheard of up there) and dropped the hook (probably on a rock bottom) and it held well enough for the task at hand. My mate always helped tail the line connected to the backstay at the winch and through a clam cleat to hold things if I needed a rest. I just loosened and released the rigging as necessary, muscle-dropped the mast and used the dinghy to go forward and sort things out. It was a very high reach, but I was successful. After I got the mast back up it started to rain….. I later drilled a hole in the truck to insert a stainless wire restraint, so the halyard cable could not be thrown off the sheave again. I have toyed with analyzing more mechanical methods for raising the mast now that I am older, less strong, and my first mate has passed on. That is what piqued my interest on your article. The Flicka is ready-made (Bingham designed it in; I am sure) for this raising procedure. The Flicka doesn’t have many complications, since there are double lowers in perfect position for the bridle attachment, and the cap shrouds are neatly centered to the mast. The Lancer is not so nice. It has a single set of lowers, and the chain plate has about 1” between the 2 connections for uppers and lowers. These are also set about 3” aft of mast centerline. The original Lancer design was a tabernacle (not exactly the proper technical term, but we will go with it) with the slot in the tabernacle tabs, and a through bolt for securing the mast. I would say this is the usual case for production trailer sailor boats. I have never been wild about the uneven up-and-down friction-prone mast butt action and the associated movement reflected in the rigging connections during stepping. I do have a strong toe rail to connect the bridle, but the chain-plate bridle connection will not work geometrically. I have purchased a hinged tabernacle plate from Ballinger Spars, which will smooth out the rotational process down there. However, the negative thing it does, is place the pivot point about 3” in front of the mast centerline. The hinge movement is forward of the mast (eccentric) and translates to about 3” up-and-down movement (tensioning or slacking) of the cap shroud/ bridle assembly while stepping the Lancer mast. With the eccentric hinged plate pivot, (while rotating up), the mast butt raises momentarily for about 1/4” (slackening the rigging) and then drops down 3” (requiring an equal amount of rigging slack or things will go into tension, which is no good). The shrouds or bridle assembly must allow a lengthening of 3” during rotation of the mast butt into final position (as determined by graphical analysis). On lowering, the movement is opposite, so the shrouds will slacken throughout rotation without causing any tension problems, and there is plenty of play being created to keep any stresses from developing. I suppose the key in my case is to set the bridle configuration when the mast I up, thus ‘dimensionally building in’ the 3” movement required into the bridle/shroud system. Thoughts? The following is an analysis of the forces on the Lancer rigging dimensions and mast weight: The mast (Kenyon 3550) is 28’ long and weighs in at 62 pounds. I arbitrarily rounded to 70 pounds for these calculations. The moment to initiate lifting the mast is 980 foot pounds. (28’x half the mast length x70 pounds – assume equal weight distribution per foot.). That is to say, if the mast is on the ground and you lift one end, it will take 35 pounds force through a distance of 28 feet (=980 foot pounds of moment acting on the mast to lift one end off of the ground). But in raising the mast, the force is pulling more aft than up (requiring vector analysis which I will get to). I am currently considering a 10’ jibboom mounted at the hinge point and not higher on the mast where the boom lives, which changes the numbers- (no bending forces on the mast – which are not really great enough to mean much to the 3550). Also in the Flicka case, boom length (as with lancer) is probably about 8’. A 10’ jibboom lowers the forces more than an 8’, but using the existing spar is practical. It is probably prudent for me to reconsider and re-calculate using the boom in its usual position. A few years ago, I designed and had a fitting made to connect a jibboom to the mast foot, so I was considering using it. So, running the numbers based on the Lacer backstay distance to the mast and initial lay of the mast, it would take (rounded) 103 pounds of tension in the backstay from the mast truck to the jibboom, and 125 pounds of tension from the jibboom to the backstay connection point. Compression loading in the 10’ boom is 114 pounds. Yes, one can use Eulers equation to analyze buckling forces, but I didn’t do it. Following good engineering practice with a factor of safety of at least 2, these numbers would be double the values shown for design checking of adequacy of rigging and spars. Confirming your experience, as the mast goes up, the center of gravity moves aft, requiring less and less force to raise the mast (and the geometry is changing) to increase efficiency of the forces as the mast goes up. 30degrees=858 ft lbs, 45 degrees=700 ft lbs, 70 degrees=350 ft lbs. 70 degrees into the lift, it would equate to 10 pounds of perpendicular force applied at the top (the center of mast mass has shifted to only 5’ in front of the final mast position). With a 4:1 ratio applied on the backstay, the pull on the line is about 31 pounds force for the Lancer System. The Flicka system is somewhat more (I don’t have the dimensions to analyze it), but from your description it was probably 40 pounds or less to start the raise, and then the tension required reduces as the mast goes up. Since the pull for the lancer scenario calculates in at around 31 pounds, I am planning to run the bitter end of the 4:1 through a block at the stern, to the bow, through a blocks on the bow, and use the anchor windlass to pull the mast up (the windlass maximum has 400 pounds of tension available). So even with friction losses, there should be no issue. I have a windlass switch in the cockpit, and a second hand-held remote at the forward hatch. It is a very convenient setup for going forward and guiding the mast or sorting out issues. Also, after my spouse passed, I put a winch at about 5’ high on the mast, and I ran the raising line there, instead of needing someone tailing at the cockpit. It is easier (almost necessary) to have a helper with me at the mast. I have lowered the mast alone with this manual system by taking wraps on the winch and playing out slack while catching the mast. However, without a jibboom, the forces are tougher to man-handle alone at the end of the lowering process. Comments are appreciated, as there is always something else to be considered or learned. Thanks

Jim, Thanks for reading and taking the time to engage. You have certainly been thinking about this! You get far deeper into the physics than I ever have and I suspect, many readers and sailors. Regarding seizing the rings on, I don’t overthink it. I have some net twine and I wrap and figure-eight it until I am sure it is strong enough. They are not permanent installations but are easy for me to put on as needed. Thoughtful marlinspike would make a nice permanent install. I have seen a different Flicka install that had the cap shroud turnbuckle placed at the pivot point. This removed the need for a seized-on ring and also gave a nice pivot point that does not bend the wire. Kinking the wire is my big concern, but the forces and the pivot point have not been high enough to do this, so without doing the physics calculation, the stress is low. Regarding the extra slack in the cap shrouds to accommodate that extra lift that occurs as the mast tips forward, no, I did not mention it, but it is a thing. I learned of that when I did not have them slack enough on a lowering. I recognized what was happening, so rather than forcing it, I backed off, adjusted, and restarted. Article scope naturally means some things are left out. That is good intel on bending your boom though. I have found on a sailboat, that if something feels like it is not running free, something is wrong. I don’t force it.

Thanks for the reply, Joshua.

I am leaning toward installing a permanent 4-hole triangular plate in the cap shroud at the bridle connection. This would create clear movement for hinge point attachments, and address stresses that can occur there. The rest is just a matter of rigging things up.

Best wishes in the new year.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Notify me via e-mail if anyone answers my comment.

Racing Continues Today Dramatic Collision at SailGP Sydney A collision between Great Britain and Japan took both teams out the race — and out of the remainder of the Sydney SailGP regatta.

TEMPORARILY BOATLESS What Should Chuck Hawley’s Next Boat Be? Chuck Hawley has sold his most recent boat and is hot on the trail for a new one.

Sponsored Post Skippers Wanted: US Coast Guard-Licensed Captains for Charters and Private Lessons For power & sail. Hourly rate from $50 up. Weekend and weekday work available.

Let Your Lights Shine Lighted Boats Continue to Dazzle the Bay The Lighted Boat Parades continue! Tonight, the St. Francis YC’s Decorated Boat Parade in San Francisco will travel between Crissy Field and the Marina Green.

Sponsored Post Stuff Your Stockings with Latitudes The perfect stocking fillers. And they're free!

Tropical Boating

Stories about Boats and Boating

- The Perfect Solo Mast-Raising System for Small Sailboats

April 19, 2010 By Tom 18 Comments

I have seen lots of different techniques and contraptions used to raise and lower the masts on small sailboats. All suffer from the same problems for solo sailors, and I recently came across a system that solves all of them neatly and for a fairly low price.

While not tremendously heavy, small sailboat masts are long and awkward to handle, tending to sway to one side while being lowered or raised. It is possible with most boats to stand at the stern and pick up the mast and just start walking forward and pushing it up. The problem comes when you have to step up onto the cabin top while holding a heavy mast high above your head. It's usually a long step, and most people can't do it.

Instead of lifting the mast by hand, many opt for a gin pole or A-frame and use the boom vang to get the mechanical advantage needed to pull the mast up.

Some trailers are fitted with a tall pole, allowing the trailer winch strap to be led to a halyard and used to crank the mast up and down. The A-frame support tends to hold the mast over the center of the boat, but gin poles on the boat or on the trailer will allow it to sway back and forth unless stabilizing baby stays are used.

Using the trailer winch to crank the mast up and down means that singlehanded sailors can't see what is going on up on the boat, and it obviously precludes raising and lowering the mast while on the water.

These difficulties are further compounded by the fact that small sailboats are covered with winches, cleats, boarding ladders, small outboard engines, etc., all of which tend to snag the shrouds or backstay as the mast goes up. If something snags, a sailor who is rigging the boat alone must find a way to hold the mast in a partially raised position while clearing the snag.

It is important that the solo sailor be able to keep a sharp eye on all the rigging and stop immediately if any resistance is felt. A snag can mean moving from your position on top of the boat or at the trailer winch all the way to the stern of the boat, where the backstay has managed to catch the rudder or boarding ladder. It is often impossible to leave the mast precariously hanging in the air, so it must be lowered to fix the problem.

The terminal fittings on the ends of the shrouds are strong when in position and tensioned, but they can lodge themselves sideways as the mast is coming up and bend when placed under load. The fittings that hold the upper ends of the shrouds in the mast must rotate as much as 90 degrees as the mast goes up, and if they lock up instead of turning freely, it is easy to bend the swage fitting when they come under tension as the mast is nearly stepped. Down at the deck, the fittings must also rotate as the shrouds go from lying aft on the deck to standing up straight. Singlehand sailors must watch the ends of the rigging carefully to ensure that all of them are operating as intended while the mast is going up. If a fitting binds up, once again it becomes necessary to either leave the mast hanging or put it back down to correct the problem and try again.

Boats with roller furling jibs present an additional problem, as the jib furler drum tends to bounce down the deck and the sail itself acts like a giant snake having a seizure. The furler drum and forestay end fittings can scratch the deck of the boat and can get snagged on bow cleats, opening hatches, and other hardware around the foredeck as the mast is being lowered. When raising the mast, the roller furling jib generally does not want to slide forward on the boat by itself, and must be pulled along and kept near the center of the boat to avoid kinking the forestay wire or binding up the fitting that holds the forestay to the mast.

Last but not least, the mast needs an appropriate place to land when it comes down , and a good place to start on its way up. Sailors must use a mast crutch of some kind, and for trailering a sailboat it helps if the crutch has two positions: a low position for holding the mast during transport, and a higher position to give a little head start when raising the mast. Having a roller on the top of the crutch is also handy for solo sailors because it makes it easier to move the mast back and forth from trailering position to the mast step.

The Mast Raising Solution for Single-Handed Sailors

I recently saw a solution that addresses all these problems and makes single handed mast raising on the water or on the trailer a fairly simple procedure . This system was in use on a Precision 23 sailboat, but can be used on any small sailboat. The boat has a mast raising pole for a MacGregor 26M with an ingenious addition to help manage the furling drum, a set of baby stays to hold the mast on centerline, and a small dinghy motor davit mounted on the stern and outfitted with a U shaped mast crutch. The owner of the boat put a lot of thought into this system because he wanted to sail his boat from his dock behind a low bridge from the harbor. Even though it uses a MacGregor mast-raising pole, this system can be installed on nearly any small sailboat.

Click on any photos for a larger view:

| Above: A side view of the sailboat with the mast raising system ready for use. This system can be installed and used on nearly any small sailboat to make solo mast-raising easier. | A closer look at the MacGregor mast raising pole and how it is attached to the mast. The MacGregor pole is a tiny trailer winch mounted on an aluminum tube with a block and eye strap on opposite sides of one end and a fitting on the other end to secure it to the mast base. The winch has a clutch instead of gears and a pawl lever, and can be cranked in either direction without flipping a lever. It can also be let go at any time without freewheeling, an important safety feature in this application. A bail is installed in the mast about 5' off the deck. There is a line tied to the middle of the mast-raising pole that has to do with furler management, as the next pictures illustrate. |

| How the mast raising system is attached at the bow of the boat. A line from the eye strap on the tip of the MacGregor pole leads to a large snap shackle that snaps around the bow rail. The line from the middle of the mast raising pole, with a little slack left in it, is also tied to that large snap shackle after being led through a snatch block which is clipped to the furler drum. | As the mast is lowered, the furler drum rides up that piece of line and ends up suspended above the forward hatch when the mast is down. On the way back up, the furler rides back down the line, remaining over the center of the boat and safely clear of the deck. In addition to keeping the furler from scratching the deck or getting hung up on something, this little bit of rigging also tends to force the furled jib to hang above the center of the mast. |

| This picture shows how the MacGregor mast raising device is attached to the tabernacle mast base of the Precision 23. The plates used are actually a small boat hinged mast step available from Dwyer, and they happen to fit perfectly on the Precision 23 mast step, also from Dwyer Masts. One hole through the mast step on the 23 was all that was required to attach the unit. | This picture shows the upper end of the MacGregor mast raising pole and the attachment to the mast of the P-23. The line from the winch on the MacGregor pole is led through the block at the tip of the pole and attaches to a ring. Also attached to the same ring are the two stabilizing stays which prevent the mast from swaying. The ring is shackled to a bail through the mast, so the one shackle connects the two baby stays and the mast raising line to the mast bail all at once. |

| The mast raising "baby stays" on a sailboat must be positioned in line with the pin holding the base of the mast in the tabernacle. As the mast rotates up or down around that pin, the raising stays remain taut, preventing any side to side motion by the mast. The problem on a Precision 23 is that there is no point on the boat which is in line with that pin. This problem was solved with a pair of stainless steel chains attached to stanchion bases in front of and aft of the mast on each side of the boat. When stretched tight, there is one link of chain on each side which is aligned with the mast tabernacle pin, and the stabilizing stays are shackled to those two links of chain. A Com-Pac 23 owner suggested locating that point in space by putting a long dowel the same size as the mast tabernacle pin through the tabernacle and using it to locate the correct link of baby stay chain. This setup was made so that the mast raising system could be quickly disconnected but not completely detached. The mast raising pole could just be left to rest on the deck with all the lines and hardware secured to it while going for a short sail. In that position, the chains would clatter around on deck, so the owner installed canvas sleeves over the chains to protect the gelcoat on the deck and reduce the noise. | This picture shows a small dinghy engine hoisting davit installed in the stern of the Precision 23, serving double duty as a mast crutch. To serve as a mast crutch, it has a metal V covered by a piece of hose on a custom support which is lashed to the tip of the davit by a few hose clamps. It is also in a good position to use for lifting the outboard engine off the transom bracket, and could be used for its intended purpose as a dinghy engine davit as well. This arrangement serves well for lowering the mast to go under a bridge, but for single hand trailering a much better solution would be to mount a roller on a mast crutch. The dinghy engine davit is an innovative solution, but an easier method would be a simple pole which can be set into a spare set of rudder pintles and gudgeons mounted alongside the ones in use on the rudder. The small offset from the centerline of the boat can be corrected by mounting the roller off center on the pole. |

| A mast support crutch with roller on a different Precision 23. The support can be extended for easier mast raising and lowering, then retracted for a lower profile when trailering the boat. On this prototype we discovered that it is important to install blocks on the pintel/gudgeon arrangement to prevent the whole pole from rotating. The roller works well when walking the mast forward and back from the step to its trailering position, but it only works well when it is aligned with the mast. Pintles and gudgeons are designed to make rudders easy to turn, and they make the pole much too easy to misalign. | This one was intended for use when the boat is on the trailer, so it just uses the same attachments as the rudder, but modifying the system for use on the water would just mean installing a duplicate set and offsetting the roller to remain on centerline. With an offset roller, it would become even more important to have some way to lock the pole and prevent it from rotating. Another lesson from this prototype was to avoid making tall guides/retainers on either side of the roller. We made them tall to prevent the mast from escaping, but it does not want to jump off the roller, and the tall guides hang up on the upper shrouds as the mast is moved fore and aft. The shrouds would ride right over shorter guides. |

This system can be adapted to fit any small sailboat, and it makes stepping the mast by yourself a much easier task. If a snag occurs during mast raising, it is possible to leave the mast partially raised to go and clear the snag. The winch used on the MacGregor pole is self-braking and almost silent, and the operator can see everything while cranking it. The extra length of line to force the jib and furler to ride up and down the centerline of the boat is a stroke of genius. The addition of a properly designed roller mast crutch makes moving the mast back to the step by yourself easy for one person.

Update: May, 2012 - Since I wrote this article, many people have contacted me asking whether I sell this mast raising system or know where to buy it. The answer to both questions is no, at least not as a package. You will have to buy the various parts and put them together yourself.

You will need the following items to assemble the mast raising system:

- A sturdy pole about 6 feet long

- A small self-braking trailer winch and hardware to attach to sturdy pole

- A way to attach the pole to the mast base

- Some sailing blocks and snaps

- Some low stretch rope

- Some chain for the centering stays , if your boat requires these

- A stainless steel bail to attach to the mast

- Probably a few things I forgot, but that will become apparent along the way

The first three items on the list are to make your own mast raising pole of the type sold with MacGregor 26M model boats. I would simply buy one from a MacGregor dealer instead of making one, but you can probably make it a bit cheaper. I would not mention to a MacGregor dealer that you intend to use it on a sailboat other than a MacGregor, as they might have liability concerns.

December 27, 2008 at 12:27 pm

Thanks for a great article. I’ve been reading other articles about mast raising systems, but they never had enough pictures to help me visualize exactly how things worked. The extra line for the furler is also great as it solves a problem I’ve seen several people discuss.

June 18, 2015 at 9:33 am

I have built one for my 1980 Macgregor 22. I would be willing to build one for the cost of materials plus $ 100 labor. It would be custom made for your boat. All you need to do is provide pictures of the mast base and tabernacle. You may contact me at: [email protected] Leave a contact email or phone number.

January 29, 2009 at 12:25 pm

This is the design I will follow for my boat. Thanks for the great documentation

April 23, 2010 at 11:49 am

I’ve got a Luger Tradewinds 26. I recently looked at the MacGregor system at a local dealer. It sells for about $150.00. I was going to buy one but then decided to make my own. I bought a piece of 2″ electrical conduit, a 600 # winch and a small pulley for about half the price of the manufactured unit. My only issue is that I don’t have a hinged mast step so I’ll be fabricating a bracket that suits my setup. I’d have to do that with the manufactured system, too. When all is said and done, I’ll probably be about $50 to $75 cheaper.

March 1, 2011 at 11:19 am

Great article, Ray! For those of you wishing to purchase the mast-raising pole, contact MacGregor Sailboats.

May 16, 2011 at 11:11 am

In the past 25 years, I’ve fabricated both gin poles and “A” frames to raise and lower the masts on boats from 21-28 feet. The 21 footer had a steel mast that was very heavy. My “A” from was made from 1″ square aluminum “pipe” with 1/8″ thickness. A bolt with eyes on each end passes through both legs with a bronze spacer between them. This functions as a hinge between the legs. One eye attaches to the forestay or topping lift and the bottom eye attaches to the tackle. The bitter end runs back to the cockpit/mast area where the skipper can control both the mast and the tackle. The bottom of each leg must hinge close to a line passing through the mast bolt and far enough apart to impart stability. Often, the cabin top is the only alternative. I placed eyebolts through the bottom of the legs with closely matching eye bolts on the cabin top. I used two eyes on the cabintop about 3/4″ apart. A simple pin with a keeper or a bolt passes through the 2 eyes of the cabin and the one eye of the “A” frame.

June 2, 2011 at 11:09 am

This is an interesting sytem. I’ve built and used one at the URL below. They obviously differ in a few ways but rely on similar principles. They also suffer from the same weak links, the attachment point for the pole to the mast or step in your case. And the auxiliary stay set-up.

To be honest, I don’t like the idea of putting through holes in my mast for the bail or using my pintles for the crutch. The crutch is the easiest to work around. For that, I’ll take a piece of galvanized pole from the depot; try to find a cap for the bottom; drill two through holes in that to attach a pair of eyebolts which I can use to secure the pole laterally to the rails. If I can’t make a height-adjustable crutch so be it. I’ll fix it right above the cabin roof.

For the attachment point. Since I’m using a system that attaches differently to begin with, I’ll leave that, but I have issues there.

For the auxilliary stays. I’m really worried here. In a single handed operation this may be the weakest link. Perhaps this how the phrase “things starting going sideways” was coined.

I like the chains. I’ll use them. I have chains for my stands, but it’s not easy to find guide wires like the one used here for the connection point. They look like old stays cut down. The process I used ties a tight line around the mast connected vertically to one of the halyards (instead of the bail on a through bolt), and attaches the baby stays there. I think I’ll try to find some low stretch line to make the connection from the loop on the mast to the chains. I think it’s really important that this be tight so clearly my idea of using the halyard suffers a bit (too much give).

Here’s that URL for the gin pole: I put this together in 2 hours of twilight with a circular saw and my drill. I take no credit for the invention.

http://www.google.com/imgres?imgurl=http://slowflight.net/upgrades/images/GinPole.jpg&imgrefurl=http://slowflight.net/upgrades/tips-GinPole.html&h=460&w=300&sz=32&tbnid=iyzi45IS37IlbM:&tbnh=128&tbnw=83&prev=/search%3Fq%3Dgin%2Bpole%26tbm%3Disch%26tbo%3Du&zoom=1&q=gin+pole&usg=__MAJzPBn9ofV8lK2r0D_01WD7ZQM=&sa=X&ei=p4bnTZCoCqnj0QGirvGCCw&ved=0CCgQ9QEwAw&biw=1131&bih=687

November 10, 2011 at 10:56 am

great idea ,used to lift a 20′ pole in the ground. To put a light. Thank you sir.

February 20, 2012 at 10:55 am

I agree, this is by far the best/safest/easiest “Mast Rising System” I have seen! I’ve been wanting to build this system for two years now. I finally was able to either collected/make all the necessary parts to put it together. Thanks for the head start! By the way, if anyone is interested, I can make them one and ship it to their house. I don’t have a price in mind right now, but interested parties can call me.

Thanks Pat 513 891 5112

October 11, 2012 at 2:07 pm

Hello, That system looks great! I am interested in putting something together for our Ericson 25′. There is no mast hinge currently so I need to piece together the stainless steel components. I’ve called Dwyer and they were unable to help determine the parts after looking at the photos on this article.If you could help I’d greatly appreciate it. Maybe Pat Maundrell could help? My cell # is (828)337-5899 and email is [email protected]

July 20, 2014 at 11:02 am

Catalina, Factory Yacht, nor MacGregor will sell to the product. I have searched for at least 2 wks. I discovered the solo-mast raising system for small boats on Tropical Boating.

Can you built one for me or any references.

cell 434-242-1859

Thanks, Randy Boone

March 29, 2015 at 7:54 pm

Do you still make tis mast raising system

June 21, 2015 at 12:28 pm

I have a Catalina 22′ Sailboat & need a Mast Raiser. Are you interested in making one? If so how much would it cost?

July 14, 2015 at 10:23 pm

I’m not interested in making one. I’d recommend going to a MacGregor dealer and buying one of theirs and then adapting it to your boat.

April 22, 2012 at 10:52 am

This link was sent to me today by the seller of the (Australian design) Castle 650 (21’4″) that I bought yesterday afternoon. He has always sailed with a family crew of 4 or more, whereas I almost exclusively sail solo, and mast raising was looming as the biggest problem for solo sailing the Castle that I hadn’t solved yet! With some minor adjustments to the baby stays I now have my answer.

I’m not sure what to make of the “where do I buy one” type replies – it’s a bunch of standard components which you buy and build the parts you need to suit the boat you’ve got. The important stuff is the idea, how it works, not the particular set of parts used on one boat somewhere in North America! I guess its because I’m an engineer and because boat production runs in Australia are so much smaller, so no one expects to be able to buy complete complex systems designed specifically for their boat.

May 3, 2012 at 10:51 am

Hello, excelent system, where can I get it, I really need it for a macregor 26 ’92

May 27, 2013 at 12:37 pm

I followed the instructions and now have a great mast raising system for my precision 23. I am interested in the small crane that you use to hold the mast for going under bridges. (I already have the pole for trailer transportation). Do you have a picture of its installation and what type it is and where you purchased it.

May 31, 2013 at 6:38 am

Angus, I have no other pictures of that small crane on the Precision 23 stern rail, but it is just a stainless steel dinghy davit that the boat owner bought at a marine store. He put a piece of rubber hose on it to prevent it from scratching the mast. I do not know the make/model of davit nor do I recall exactly how it was installed. I do remember that it was not custom built. It’s a commercially available davit that is used to pick up dinghies and hoist outboard engines on and off of them. Sorry I can not be more helpful! Good luck!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- BOTE Aero Rover Inflatable SUP MicroSkiffs!

- ePropulsion Electric Outboard On A Picnic Cat

- Com-Pac Picnic Cat Fun!

- Selling the Stray Goat

- June 2021 Stray Goat Projects

- How to Dock an Outboard or Sterndrive Powerboat in 3 Easy Pictures

- Small Outboard Engine Tilt and Trim: Theory and Practice

- Tying Boats to Docks Using Springlines

- Deep V, Shallow V, or Variable Deadrise Hull Performance

- The Com-Pac Sun Cat: A Review

- Building a Live Bait Well For A Small Boat

- Choosing the Right Propeller For Your Boat

- Rebuilding Whaleboat Tenders Part 5: Boat Parts Shopping Day

- More Boston Whaler Modifications

- Boat Building (5)

- Boat Handling (10)

- Boat Repairs & Upgrades (50)

- Dinghies (4)

- Boating Fun (30)

- Boating Safety (7)

- Buying & Selling Boats (5)

- Classic Boating Tales (25)

- Fishing (16)

- Drone Stuff (3)

- Trail Camera Pictures (18)

- Tropical Fruiting (1)

- Kayaking (22)

- Powerboating (18)

- Races & Regattas (14)

- Sailboat Cruising (15)

- Sailboat Reviews (7)

- Antique Fishing Tackle

- Big Air Wakeboards

- Binocular Bargains

- Boat Parts Online

- Boat Seats for Sale

- Boat Wear Bargains

- Boating Memorabilia

- Discount Marine Electronics

- Ice Fishing Shop

- Maritime Antiques

- Nautical Motif Gifts & Decor

- Slingin' Steel Spearfishing Bargains

- Sun Cat National Championship Regatta

- Tropical Affiliate Marketing

- Tropical Web Works

- Tying Flies

- Boat Paddles

- Dock & Boat Cleats

- Fender Cleats & Holders

- Fender Covers

- Abu Garcia Spinning Reels

- Daiwa Spinning Reels

- KastKing Spinning Reels

- Okuma Spinning Reels

- Penn Spinning Reels

- Pflueger Spinning Reels

- Quantum Spinning Reels

- Shakespeare Spinning Reels

- Shimano Spinning Reels

- Zebco Spinning Reels

- Baitcasting Reels

- Spincast Reels

- Abu Garcia Rod & Reel Combos

- Baitcast Rod & Reel Combos

- Okuma Rod & Reel Combos

- Quantum Rod & Reel Combos

- Shakespeare Rod & Reel Combos

- Spinning Rod & Reel Combos

- Ugly Stik Rod & Reel Combos

- Tackle Bags

- Tackle Boxes

- Fishing Backpacks

- Inflatable Dinghies

- Inflatable Kayaks

- Inflatable SUPs

- Kayak Paddles

- KeelGuard Keel Protectors

- Chartplotters

- Fishfinders

- Fixed-Mount VHF Radios

- Handheld GPS Units

- Handheld VHF Radios

- Pelican Waterproof Marine Boxes

- Fishing PFDs

- Inflatable PFDs

- Kayaking PFDs

- Survival PFDs

- Survival Suits & Immersion Suits

- PFDs for Infants

- PFDs for Children

- PFDs for Adults

- PFDs for Dogs

- Throwable (Type IV) PFDs

- Right-Hand Propellers

- Left-Hand Propellers

- Aluminum Propellers

- Stainless Steel Propellers

- Three-Blade Propellers

- Four-Blade Propellers

- Forums New posts Unanswered threads Register Top Posts Email

- What's new New posts New Posts (legacy) Latest activity New media

- Media New media New comments

- Boat Info Downloads Weekly Quiz Topic FAQ 10000boatnames.com

- Classifieds Sell Your Boat Used Gear for Sale

- Parts General Marine Parts Hunter Beneteau Catalina MacGregor Oday

- Help Terms of Use Monday Mail Subscribe Monday Mail Unsubscribe

A great mast raising system

- Thread starter saddlesore

- Start date Sep 5, 2018

- Hunter Owner Forums

- Smaller Boats

Slick looking idea. What type of fitting do you have attaching the tubes to the mast slide? Any chance you have pics of that part? Thanks Sam

I don't have a picture now but will get one on Friday. I use a roller between the poles and eye bolts about 3" below with a short wire to a center eye. Watch the youtube video of the guy from the UK who invented it search "mast raising tool".

That is interesting. When the mast gets near vertical it looks like the roller sits pretty low on the mast, leaving a lot of weight above the roller. How has that worked out for you, to get it fully vertical?

That's a really cute idea. I haven't seen it done that way before. Thanks for sharing.

It really works great. I use 7' poles that takes it right to the boom attachment and fully vertical with enough pressure to attach the front stay. You use the mainsheet attached to the "tool" and to the boomvang eye. I was blown away by the youtube video and have found it accurately shows how simple it works.

saddlesore said: I don't have a picture now but will get one on Friday. I use a roller between the poles and eye bolts about 3" below with a short wire to a center eye. Watch the youtube video of the guy from the UK who invented it search "mast raising tool". Click to expand

Interesting approach! On the video the supports extended somewhat beyond the roller which would provide additional security against the mast rolling off the side in the case of heavy winds or other inadvertent lateral forces.

Thank you Sooooooooo much! just finished lowering my mast with your rig. so much better than the jin pole i had.

Love this idea, I'm going to make one this weekend!

This is a great idea and one which I copied when I saw it on You Tube.

So I thought I was going to try something really cool. I measured and it seems I need 9 ft from the companionway to the mast. I was at Home Depot and noticed a 10 ft aluminum ladder that was mangled a the last foot. That would have probably been more work to cut the rivets off and narrow the ladder but I thought it would make a lightweight but strong option. I needed it to be discounted to at least $50 to make it worth it but the manager wouldn't go for it. I did decide to use two large castors mounted upside down on a crossbar instead of a bow roller on an axle. I'm going to do the same thing on my mast support to aid in sliding the mast back and forth.

Crazy Dave Condon

The wire crimped should always have two crimps in case the single should ever fail

Project_Mayhem

Fred said: supports extended somewhat beyond the roller Click to expand

replaced masts when one failed. New mast with shipping for example H260 is around or greater than $2,000

- Dec 17, 2018

I may try this at some point, but the toughest part of my mast raising is getting the mast back far enough over the crutch to pin its base, because of the spreaders. These photos look a bit different than what I have, as I can see that when the mast is in the crutch, before the rig has been used to start lifting it, the spreaders are forward of the crutch. I have a Z-spar, and maybe the position of the spreaders is a bit different that this pictured mast. I did something similar to these pics, built a wooden attachment with a trailer roller at the top that I bolt on to the metal crutch. I leave the metal crutch in its lowest position (the one used to store and transport) and bolt on my extension. That extension is the right height so that when the mast is pinned and rests in it, the mast is angled high enough to clear the sliding hatch. Attached is the only photo I have at hand, but you can see the extension. I did not do anything to angle the extension toward the rear, and the slant of the transom positions the top of the extension (or extended metal crutch if used) a bit forward of the pintles. When I slide the mast back, rolling it along the roller, the spreaders stop it from rolling back far enough to attach the pin on the tabernacle. I have to lift the mast at the spreaders over the wood sides by the roller and move it back about 6 inches to get the mast base in the pinning position. That is a PITA as it is somewhat high to lift. I have thought about ways to mount the extension so it is angled back a bit, but have no good design that would be easy and structurally sound. I may have a weld shop cut the metal crutch and reweld at an angle with some sort of strengthener. Do others with a 23 find that the spreaders must be muscled aftward over the crutch to pin the mast? Any good solutions to this?

Attachments

My mast is exactly like yours. The solution to rolling the mast back on the crutch and clearing the spreaders is to cut your ears off of your crutch support. I did that and replaced my roller with one that had raised sides to it. That way the mast clears the roller and the roller holds the mast in center line as you roll it forward and aft in order to line up with the mast base. Because of the angle between the raising mast and the mast tool, the ears on the mast tool do not seem to interfere with the spreaders.

Isaksp00: I do not have a picture handy of my mast crutch/roller system but am going to the boat tomorrow and will take a pic so that you can see what I did to solve the mast moving/spreader dilema.

- This site uses cookies to help personalise content, tailor your experience and to keep you logged in if you register. By continuing to use this site, you are consenting to our use of cookies. Accept Learn more…

- Mastering the Mast: A Comprehensive Dive into the World of Sailboat Masts and Their Importance

A mast is not just a tall structure on a sailboat; it's the backbone of the vessel, holding sails that catch the wind, driving the boat forward. Beyond function, it's a symbol of adventure, romance, and humanity's age-old relationship with the sea.

The Rich Tapestry of Sailboat Mast History

From the simple rafts of ancient civilizations to the majestic ships of the Renaissance and the agile sailboats of today, masts have undergone significant evolution.

- The Humble Beginnings : Early masts were basic structures, made from whatever wood was available. These rudimentary poles were designed to support basic sails that propelled the boat forward.

- The Age of Exploration : As ships grew in size and began journeying across oceans, the demands on masts increased. They needed to be taller, stronger, and able to support multiple sails.

- Modern Innovations : Today's masts are feats of engineering, designed for efficiency, speed, and durability.

A Deep Dive into Types of Boat Masts

There's no 'one size fits all' in the world of masts. Each type is designed with a specific purpose in mind.

- Keel Stepped Mast : This is the traditional choice, where the mast runs through the deck and extends into the keel. While providing excellent stability, its integration with the boat's structure makes replacements and repairs a task.

- Deck Stepped Mast : Gaining popularity in modern sailboats, these masts sit atop the deck. They might be perceived as less stable, but advancements in boat design have largely addressed these concerns.

Materials and Their Impact

The choice of material can profoundly affect the mast's weight, durability, and overall performance.

- Aluminum : Lightweight and resistant to rust, aluminum masts have become the industry standard for most recreational sailboats.

- Carbon Fiber : These masts are the sports cars of the sailing world. Lightweight and incredibly strong, they're often seen on racing boats and high-performance vessels.

- Wood : Wooden masts carry the romance of traditional sailing. They're heavier and require more maintenance but offer unparalleled aesthetics and a classic feel.

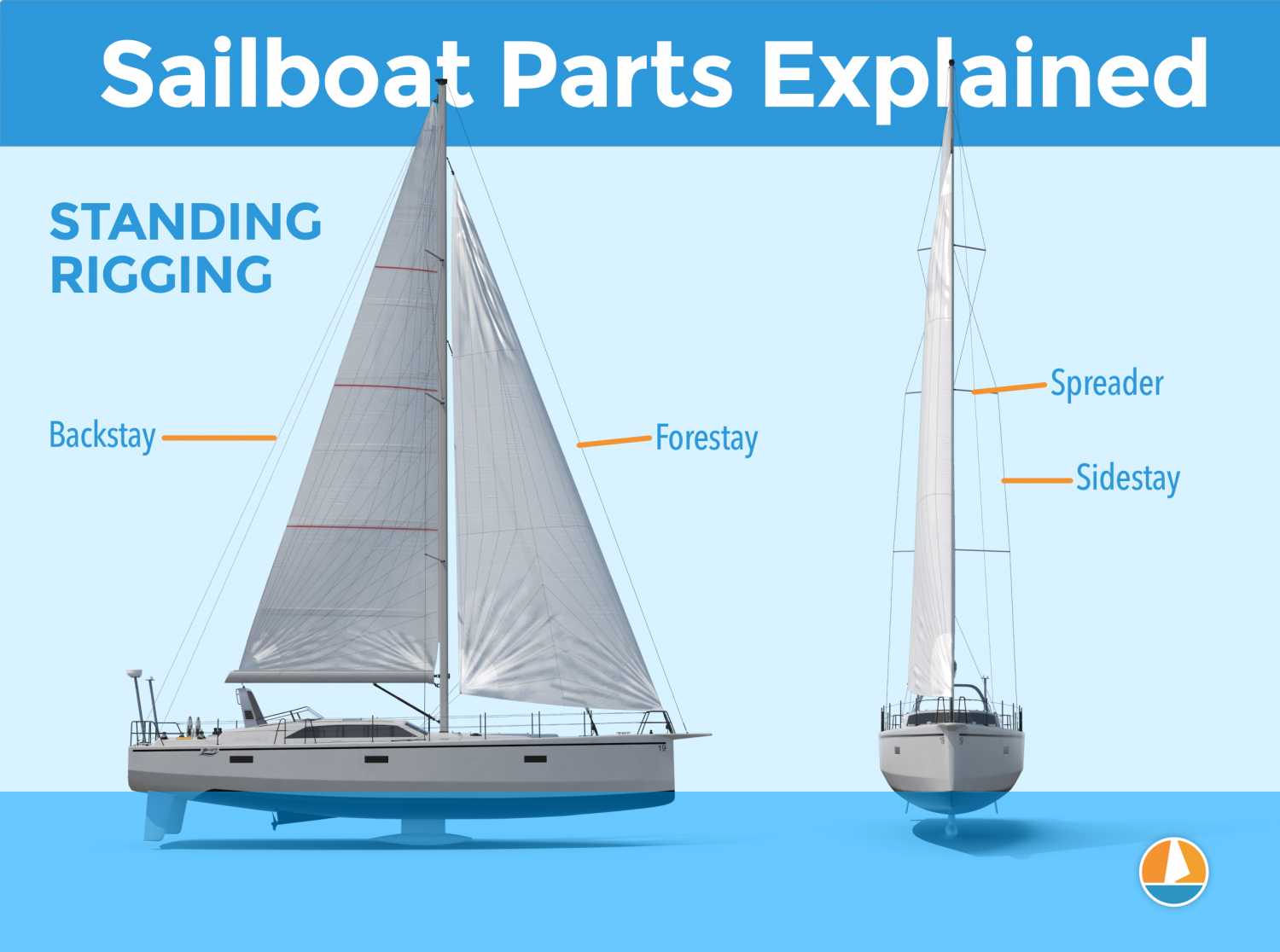

Anatomy of a Sail Mast

Understanding the various components can greatly improve your sailing experience.

- Masthead : Sitting atop the mast, it's a hub for various instruments like wind indicators and lights.

- Spreaders : These are essential for maintaining the mast's stability and optimizing the angle of the sails.

- Mast Steps and Their Critical Role : Climbing a mast, whether for repairs, adjustments, or simply the thrill, is made possible by these "rungs." Their design and placement are paramount for safety.

Deck vs. Yacht Masts

A common misconception is that all masts are the same. However, the requirements of a small deck boat versus a luxury yacht differ drastically.

- Yacht Masts : Designed for grandeur, these masts are equipped to handle multiple heavy sails, sophisticated rigging systems, and the weight and balance demands of a large vessel.

- Sailboat Masts : Engineered for agility, they prioritize speed, wind optimization, and quick adjustments.

Maintenance, Repairs, and the Importance of Both

Seawater, winds, and regular wear and tear can take their toll on your mast.

- Routine Maintenance : Regular checks for signs of corrosion, wear, or structural issues can prolong your mast's life. Using protective coatings and ensuring moving parts are well-lubricated is crucial.

- Common Repairs : Over time, parts like spreaders, stays, or even the mast steps might need repair or replacement. Regular inspections can spot potential problems before they escalate.

Read our top notch articles on topics such as sailing, sailing tips and destinations in our Magazine .

Check out our latest sailing content:

Costing: The Investment Behind the Mast

While the thrill of sailing might be priceless, maintaining the mast comes with its costs.

- Regular Upkeep : This is an ongoing expense, but think of it as insurance against larger, more costly repairs down the line.

- Repairs : Depending on severity and frequency, repair costs can stack up. It's always advisable to address issues promptly to avoid more significant expenses later.

- Complete Replacement : Whether due to extensive damage or just seeking an upgrade, replacing the mast is a significant investment. Consider factors like material, type, and labor when budgeting.

Upgrading Your Mast: Why and How

There comes a time when every sailor contemplates upgrading their mast. It might be for performance, compatibility with new sail types, or the allure of modern materials and technology.

- Performance Boosts : New masts can offer better aerodynamics, weight distribution, and responsiveness.

- Material Upgrades : Shifting from an old wooden mast to a modern aluminum or carbon fiber one can drastically change your sailing experience.

- Compatibility : Modern sails, especially those designed for racing or specific weather conditions, might necessitate a mast upgrade.

The Impact of Weather on Masts

Weather conditions significantly influence the longevity and performance of your mast. From strong winds to salty sea sprays, each element poses unique challenges. Regularly washing the mast, especially after sailing in saltwater, can help prevent the onset of corrosion and wear.

Customization and Personal Touches

Every sailor has a unique touch, and this extends to the mast. Whether it's intricate carvings on wooden masts, personalized masthead designs, or innovative rigging solutions, customization allows sailors to make their vessel truly their own.

The Role of Sails in Mast Design

It's not just about the mast; the type and size of sails greatly influence mast design. From the full-bellied spinnakers to the slender jibs, each sail requires specific support, tension, and angle, dictating the rigging and structure of the mast.

Safety First: The Role of Masts in Overboard Incidents

A mast isn't just for sailing; it plays a crucial role in safety. In overboard situations, the mast, especially when fitted with steps, can be a lifeline, allowing sailors to climb back onto their boat. Its visibility also aids in search and rescue operations.

The Rise of Eco-Friendly Masts

As the world grows more eco-conscious, the sailing community isn't far behind. New materials, designed to be environmentally friendly, are making their way into mast production. They aim to provide the strength and durability of traditional materials while reducing the environmental footprint.

The Intricate World of Rigging

The mast serves as the anchor for a complex system of ropes, pulleys, and cables – the rigging. This network, when fine-tuned, allows sailors to adjust sails for optimal wind capture, maneuverability, and speed. Mastery over rigging can elevate a sailor's experience and prowess significantly.

Historical Significance: Masts in Naval Warfare

In historical naval battles, the mast played a pivotal role. Damaging or destroying an enemy's mast was a strategic move, crippling their mobility and rendering them vulnerable. The evolution of masts in naval ships offers a fascinating glimpse into maritime warfare tactics of yesteryears.

The Science Behind Mast Vibrations

Ever noticed your mast humming or vibrating in strong winds? This phenomenon, known as aeolian vibration, arises from the interaction between wind and the mast's

structure. While it can be a mesmerizing sound, unchecked vibrations over time can lead to wear and potential damage.

Future Trends: What Lies Ahead for Sailboat Masts

With technological advancements, the future of masts is bright. Concepts like retractable masts, integrated solar panels, and smart sensors for real-time health monitoring of the mast are on the horizon. These innovations promise to redefine sailing in the years to come.

Paying Homage: Celebrating the Mast

Across cultures and ages, masts have been celebrated, revered, and even worshipped. From the Polynesians who viewed them as spiritual totems, to modern sailors tattooing mast symbols as badges of honor, the mast, in its silent grandeur, continues to inspire awe and respect.

Conclusion: The Mast’s Place in Sailing

In the grand scheme of sailing, the mast holds a place of reverence. It's not just a structural necessity; it's a testament to human ingenuity, our quest for exploration, and the sheer love of the sea.

How often should I inspect my mast?

At least twice a year, preferably before and after sailing season.

Can I handle repairs myself?

Minor repairs, yes. But for major issues, it's best to consult a professional.

Is there an average lifespan for a mast?

With proper care, masts can last decades. Material and maintenance quality play a huge role.

How do I know if it's time to replace my mast?

Constant repairs, visible wear, and decreased performance are indicators.

What's the most durable mast material?

Carbon fiber is incredibly strong and durable, but aluminum also offers excellent longevity.

So what are you waiting for? Take a look at our range of charter boats and head to some of our favourite sailing destinations.

Mast Queries Answered

I am ready to help you with booking a boat for your dream vacation. contact me..

Denisa Kliner Nguyenová

- Destination Information

- Sailing routes

- Boat owners

- Tips & Inspiration

- Sustainable Sailing

- Featured Posts: The Latest News

- Nautical Knowledge

What a sailboat mast? All you need to know!

- 8 August 2023

- 4 minute read

Alice Martin

Share the post "What a sailboat mast? All you need to know!"

If you are an avid sailor, you will understand the importance knowing about the different parts of a sailboat. There are few things as fundamental as the sailboat mast. Rising tall from the deck, the mast is an important structure that harmonises the wind and water to propel the vessel forward. In this blog post, we will explore the different components of a sailboat mast and dive into the fascinating world of single mast rigs and multi-mast rigs, each offering a unique sailing experience.

At Click&Boat, we like to keep you up to date with all things sailing. Read on to find out more about the different parts and uses of the mighty sailboat mast!

What is a sailboat mast?

At its core, a sailboat mast is a vertical pole that extends upward from the deck of the boat. It plays an important role in supporting the sails and maintaining their shape to maximise the use of wind. The material used to make sailboat masts is typically aluminum, carbon fiber, or wood, with each material offering its own unique benefits.

What are the different parts of a sailboat mast?

A sailboat mast consists of several integral parts:

Base and Step: The mast is securely fixed to the boat’s deck using a base and step, which provide stability and distribute the forces exerted by the sails.

Masthead: Located at the very top of the mast, the masthead is an attachment point for various rigging elements, such as halyards and stays.

Spreaders: These are horizontal bars extending from the mast, which help to keep the shrouds (supporting cables) away from the mast, providing better support for the rig.

Boom: The boom is a horizontal spar that extends from the bottom of the mast, holding the foot of the mainsail and controlling its angle.

Now that we have an overview of the sailboat mast let’s delve into the two primary types of sailboat rigs: single-mast rigs and multi-mast rigs.

Single – mast rigs

There are 3 different types of single mast rigs: Sloop – Rigged Mast, Cutter Mast and Catboat Mast.

Sloop – Rigged Mast

The sloop rig is one of the most common and simple configurations for a single mast sailboat. It features a single mast with two sails – a mainsail and a foresail (jib or genoa). Attached to the boom is the mainsail. The foresail secures to the forestay at the bow and a headsail furler, allowing for easy reefing and unfurling.

Cutter Mast

The cutter rig is a variation of the sloop rig, with an additional smaller headsail, known as the staysail. This configuration provides more sail area options, offering increased versatility and better performance in varying wind conditions. The staysail is set between the forestay and an inner forestay, creating a more balanced sail plan.

Catboat Mast

The catboat rig is a unique single mast configuration that features a single, large mainsail with no headsail. This makes it easy to handle, especially for beginners. The lack of a headsail makes the catboat less efficient for upwind sailing but ideal for downwind and reaching courses.

Multi – Mast rig

There are 3 different types of Multi – Mast rigs: Yawl Masts, Ketch Masts, and Schooner Masts.

The yawl rig has two masts – a taller main mast and also a shorter mizzen mast, located forward of the rudder post. The mizzen mast helps improve balance and control, making it easier to handle in rough seas. The yawl rig allows for a diverse range of sail combinations, enhancing the sailboat’s adaptability.

Ketch Masts

The ketch rig features two masts, but with the mizzen mast positioned aft of the rudder post. This configuration offers better downwind performance and maneuverability while sacrificing some upwind efficiency. Ketch rigs are popular for long-distance cruising vessels due to their versatility.

Schooner Masts

The schooner rig has two masts, with the forward mast (foremast) being taller than the aft mast (mainmast). Schooners often feature multiple foresails and square topsails on their masts, providing an extensive sail area for excellent downwind performance.

For any sailor, understanding the sailboat mast and its various configurations is essential for navigating the waters with confidence. The sailboat mast stands as an excellent example of engineering. It symbolizes the very essence of sailing – the harmonious dance between the wind, water, and the spirit of adventure. next time you set sail, take a moment to appreciate the sailboat mast. the sturdy backbone that carries you on your nautical journey. Happy sailing!

- Inspiration

Sunset Sailing: The Complete Handbook

- 31 July 2023

- Clara Chambers

Boating activities for your next adventure

- 10 August 2023

You May Also Like

Discovering Madeira: boat trip ideas to explore the island

- 7 September 2024

Your City Break Holidays to Barcelona During the America’s Cup

- 21 August 2024

What you need to know for a boat safety certificate in the United States

- 7 July 2024

Budgeting for your daily boat hire

- 6 July 2024

For your next motorboat trip: A skippered or a bareboat charter?

- 3 July 2024

What to bring aboard a motorboat: your boating checklist

- 1 July 2024

First time renting with Click&Boat? Here’s What You Need to Know!

- 30 June 2024

- About Click&Boat

Click&Boat’s guide to using a boat licence abroad

- 29 June 2024

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Sails & Canvas

- Hull & Structure

- Maintenance

- Sailing Stories

- Sailing Tips

- Boat Reviews

- Book Reviews

- The Dogwatch

Select Page

Rise Up! How to Raise Your Sailboat Mast

Posted by Zoran Glozinic | Dogwatch , Projects , Sails & Canvas

Spring is here and marinas will soon be filled with mast-raisers. And while the world is filled (to the brim?) with mast-raising solutions, I have another. I believe my method is possibly the simplest solution most applicable to a wide range of boats. It allows a sailor to raise a mast independently, without a crane, affording freedom. It also enables a sailor to do it by themself. And while most mast-raising solutions require various panoply of items a sailor needs to either purchase or fabricate—various gin poles, A-frames, lifting poles, winches, 2×6 boards, lawn-mower wheels, and mast supports mounted to rudder fittings on the transom—and while sailors who trailer their boats to various waters have to carry all of that with them, the solution I’ve come up with uses a very small amount of extra equipment, so small it can almost be carried in one’s pocket.

Everything rigged and mast ready to be raised with a tug on the mainsheet.

So, what is required and how do you rig it?

- First, to use my solution, your mast should have a mast base/step or tabernacle on which the mast can pivot. This is common.

- Next, there will need to be an attachment point on either side of the boat, aligned with the mast pivoting point—athwartships and on the same axis. You might need to get creative here because each boat is different. The two attachment points (eyes are fine) can be permanent (as in this photo), or they can be made using a steel ring and two short lengths of steel wire or chain temporarily attached to an existing hardpoint. The wider these attachment points are spaced, the better, because they serve as hardpoints to attach two sets of temporary shrouds.

- About seven feet above the mast step (or as high as you can comfortably reach up the mast when it’s vertical) on either side of the mast, there must be tangs or permanent mounts to attach the mast-supporting set of temporary shrouds. I used a length of ¼-inch threaded rod that passes through the mast and through two small hardwood blocks and two small tangs made from mild steel. I install these tangs when needed, using wingnuts. When sailing, there is nothing on the mast to snag halyards, and the two small holes are not something I worry about.

And that is it for boat modifications.

Mast successfully raised, note the athwartships attachment points on the dorade boxes and the two sets of temporary shrouds.

A close-up view of the athwartships attachment points.

To raise and lower the mast, I rig things and operate as follows. In this example, the mast is attached to a pivoting base and stowed lowered onto the bow pulpit.

- Between the athwartships attachment points and the mast tangs, I attach a set of temporary shrouds. These I made from coated wire rope (the same as used for lifelines). These will remain taut for the duration of the mast raising or lowering (because they’re attached on the same axis on which the mast pivots) and serve to prevent the mast from swaying from side to side.

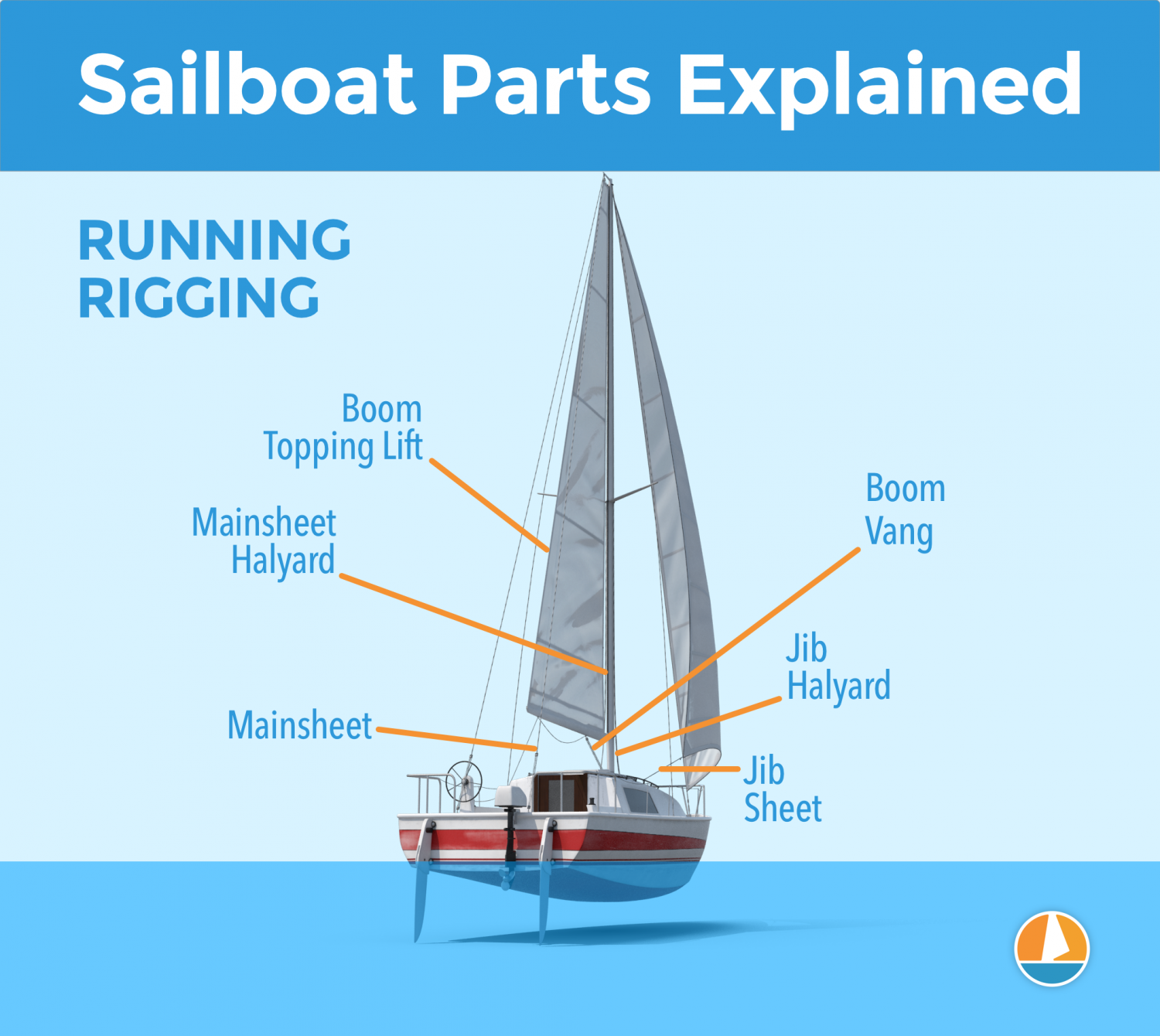

- I attach the boom like I’m ready to sail, 90 degrees to the mast, connected to the gooseneck fitting and with the topping lift and end-of-boom mainsheet rigged. I use the main halyard and boom downhaul to keep the gooseneck fixed (so it cannot slide up or down, if track-mounted).

- Between the athwartships attachment points and the clew end of the boom, I attach a second set of temporary shrouds. These I made from low-stretch braided line and they will also remain taut for the entire mast raising and lowering.

- Once all set, I pull on the mainsheet (rigged with 4:1 block-and-tackle for purchase) to raise the mast. It’s relatively easy and the mast remains in control; I can stop and start at any point in the process if needed.

If my mast was instead pivoted aft and stowed on an aft-rail support, I could still use the same method, but I would have to attach a separate gooseneck fitting on the front of the mast and some separate running rigging to function as the topping lift does.

Happy spring mast raising!

One nice-to-have modification I’ve made is to the pulpit where my mast rests when stowed. I made a wooden mast support mounted on the bow rail. The rubber roller has two positions: the lower position is used for winter mast storage, and the upper position allows for easy mast sliding, fore and aft, when getting it to the exact position in order to install (remove) the pivoting bolt/pin at the mast base or tabernacle. When not in use, I stow this support at the bottom of a sail locker.

About The Author

Zoran Glozinic

Zoran Glozinic is a retired business professional who has been messing around in boats and old cars all his life. He currently lives in Laval, Quebec, where he divides his free time between a good old English bilge-keel boat and a 16-year-old Saab car.

Related Posts

Endless Sea: Book Review

October 1, 2008

Dick Carter: Yacht Designer in the Golden Age of Offshore Racing

March 12, 2019

Susan’s Sailing Adventures: Book Review

December 1, 2002

Mudlark’s Ghosts: Book Review

April 1, 2007

Current Edition

Join Our Mailing List

Get the best sailing news, boat project how-tos and more delivered to your inbox.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Sailboat Parts Explained: Illustrated Guide (with Diagrams)

When you first get into sailing, there are a lot of sailboat parts to learn. Scouting for a good guide to all the parts, I couldn't find any, so I wrote one myself.

Below, I'll go over each different sailboat part. And I mean each and every one of them. I'll walk you through them one by one, and explain each part's function. I've also made sure to add good illustrations and clear diagrams.

This article is a great reference for beginners and experienced sailors alike. It's a great starting point, but also a great reference manual. Let's kick off with a quick general overview of the different sailboat parts.

General Overview

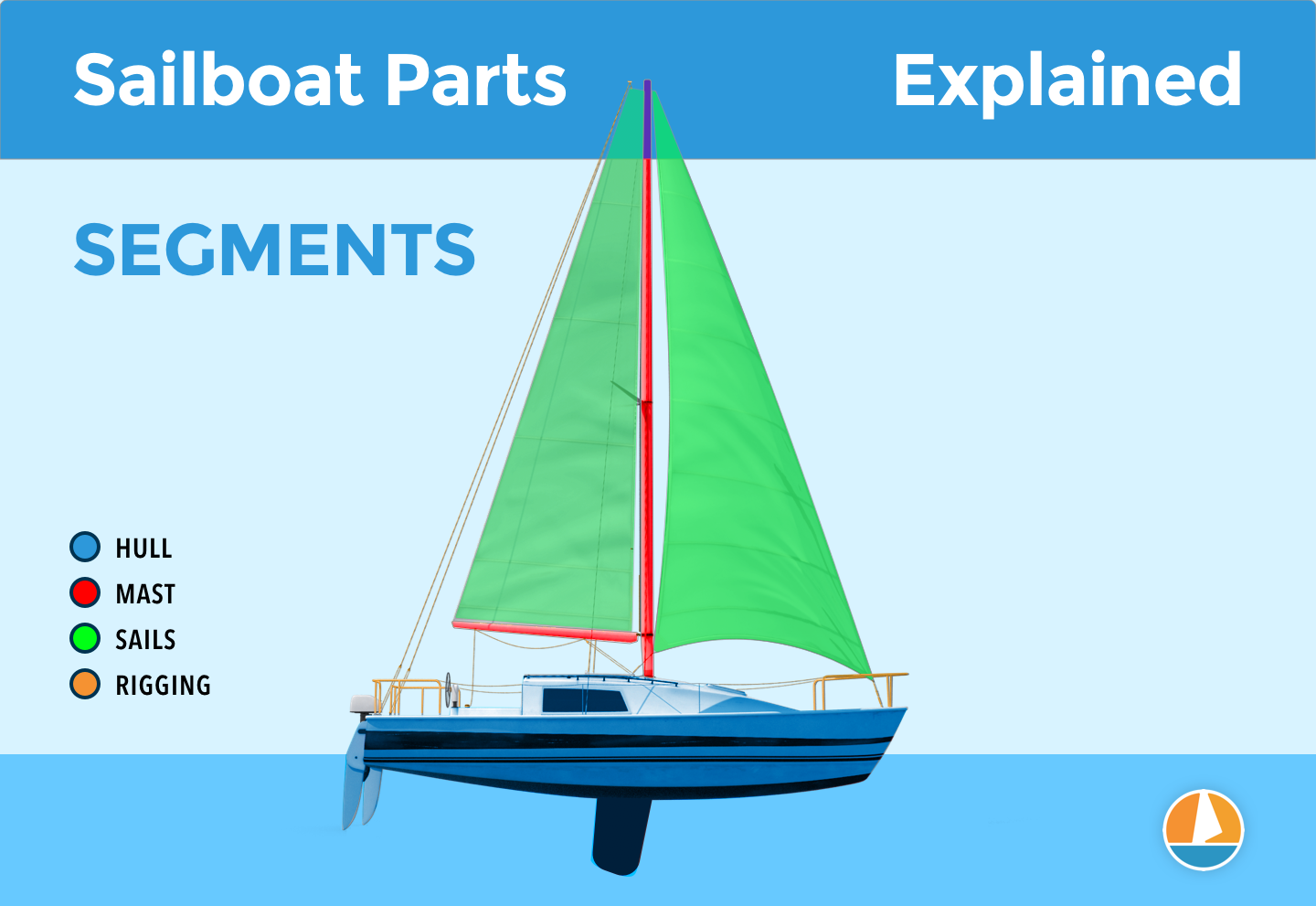

The different segments

You can divide up a sailboat in four general segments. These segments are arbitrary (I made them up) but it will help us to understand the parts more quickly. Some are super straightforward and some have a bit more ninja names.

Something like that. You can see the different segments highlighted in this diagram below:

The hull is what most people would consider 'the boat'. It's the part that provides buoyancy and carries everything else: sails, masts, rigging, and so on. Without the hull, there would be no boat. The hull can be divided into different parts: deck, keel, cabin, waterline, bilge, bow, stern, rudder, and many more.

I'll show you those specific parts later on. First, let's move on to the mast.

Sailboats Explained

The mast is the long, standing pole holding the sails. It is typically placed just off-center of a sailboat (a little bit to the front) and gives the sailboat its characteristic shape. The mast is crucial for any sailboat: without a mast, any sailboat would become just a regular boat.

I think this segment speaks mostly for itself. Most modern sailboats you see will have two sails up, but they can carry a variety of other specialty sails. And there are all kinds of sail plans out there, which determine the amount and shape of sails that are used.

The Rigging

This is probably the most complex category of all of them.

Rigging is the means with which the sails are attached to the mast. The rigging consists of all kinds of lines, cables, spars, and hardware. It's the segment with the most different parts.

The most important parts

If you learn anything from this article, here are the most important parts of any sailboat. You will find all of these parts in some shape or form on almost any sailboat.

Okay, we now have a good starting point and a good basic understanding of the different sailboat parts. It's time for the good stuff. We're going to dive into each segment in detail.

Below, I'll go over them one by one, pointing out its different parts on a diagram, listing them with a brief explanation, and showing you examples as well.

After reading this article, you'll recognize every single sailboat part and know them by name. And if you forget one, you're free to look it up in this guide.

On this page:

The hull is the heart of the boat. It's what carries everything: the mast, the sails, the rigging, the passengers. The hull is what provides the sailboat with its buoyancy, allowing it to stay afloat.

Sailboats mostly use displacement hulls, which is a shape that displaces water when moving through it. They are generally very round and use buoyancy to support its own weight. These two characteristics make sure it is a smooth ride.

There are different hull shapes that work and handle differently. If you want to learn more about them, here's the Illustrated Guide to Boat Hull Types (with 11 Examples ). But for now, all we need to know is that the hull is the rounded, floating part of any sailboat.

Instead of simply calling the different sides of a hull front, back, left and right , we use different names in sailing. Let's take a look at them.

The bow is the front part of the hull. It's simply the nautical word for 'front'. It's the pointy bit that cuts through the water. The shape of the bow determines partially how the boat handles.

The stern is the back part of the hull. It's simply the nautical word for 'back'. The shape of the stern partially determines the stability and speed of the boat. With motorboats, the stern lies deep inside the water, and the hull is flatter aft. Aft also means back. This allows it to plane, increasing the hull speed. For sailboats, stability is much more important, so the hull is rounded throughout, increasing its buoyancy and hydrodynamic properties.

The transom is the backplate of the boat's hull. It's the most aft (rear) part of the boat.

Port is the left side of a sailboat.

Starboard is the right side of a sailboat

The bilges are the part where the bottom and the sides of the hull meet. On sailboats, these are typically very round, which helps with hydrodynamics. On powerboats, they tend to have an angle.

The waterline is the point where the boat's hull meets the water. Generally, boat owners paint the waterline and use antifouling paint below it, to protect it from marine growth.

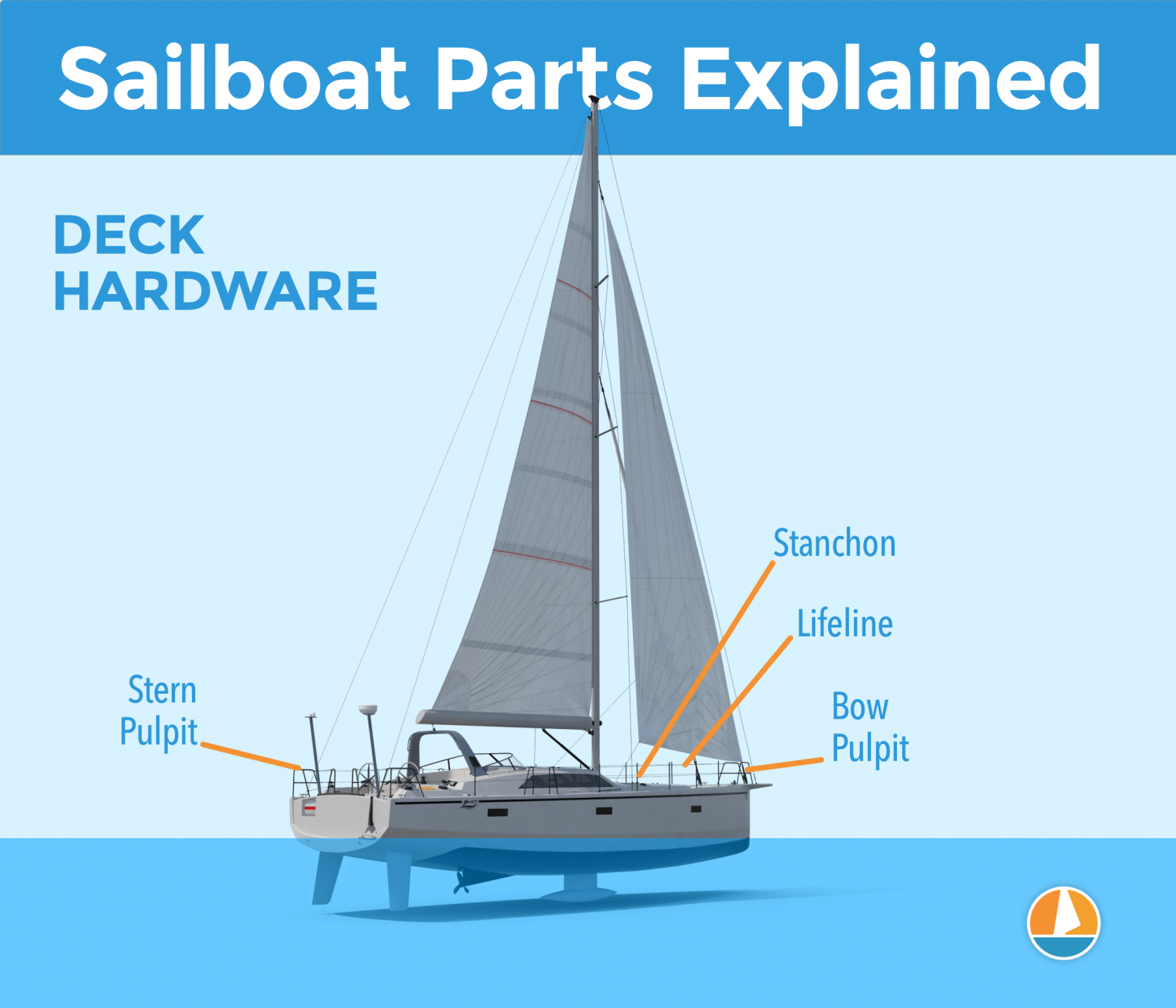

The deck is the top part of the boat's hull. In a way, it's the cap of the boat, and it holds the deck hardware and rigging.

Displacement hulls are very round and smooth, which makes them very efficient and comfortable. But it also makes them very easy to capsize: think of a canoe, for example.

The keel is a large fin that offsets the tendency to capsize by providing counterbalance. Typically, the keel carries ballast in the tip, creating a counterweight to the wind's force on the sails.

The rudder is the horizontal plate at the back of the boat that is used to steer by setting a course and maintaining it. It is connected to the helm or tiller.

Tiller or Helm

- The helm is simply the nautical term for the wheel.

- The tiller is simply the nautical term for the steering stick.

The tiller or helm is attached to the rudder and is used to steer the boat. Most smaller sailboats (below 30') have a tiller, most larger sailboats use a helm. Large ocean-going vessels tend to have two helms.

The cockpit is the recessed part in the deck where the helmsman sits or stands. It tends to have some benches. It houses the outside navigation and systems interfaces, like the compass, chartplotter, and so on. It also houses the mainsheet traveler and winches for the jib. Most boats are set up so that the entire vessel can be operated from the cockpit (hence the name). More on those different parts later.

Most larger boats have some sort of roofed part, which is called the cabin. The cabin is used as a shelter, and on cruising sailboats you'll find the galley for cooking, a bed, bath room, and so on.

The mast is the pole on a sailboat that holds the sails. Sailboats can have one or multiple masts, depending on the mast configuration. Most sailboats have only one or two masts. Three masts or more is less common.

The boom is the horizontal pole on the mast, that holds the mainsail in place.

The sails seem simple, but actually consist of many moving parts. The parts I list below work for most modern sailboats - I mean 90% of them. However, there are all sorts of specialty sails that are not included here, to keep things concise.

The mainsail is the largest sail on the largest mast. Most sailboats use a sloop rigging (just one mast with one bermuda mainsail). In that case, the main is easy to recognize. With other rig types, it gets more difficult, since there can be multiple tall masts and large sails.

If you want to take a look at the different sail plans and rig types that are out there, I suggest reading my previous guide on how to recognize any sailboat here (opens in new tab).

Sail sides:

- Leech - Leech is the name for the back side of the sail, running from the top to the bottom.

- Luff - Luff is the name for the front side of the sail, running from the top to the bottom.

- Foot - Foot is the name for the lower side of the sail, where it meets the boom.

Sail corners:

- Clew - The clew is the lower aft (back) corner of the mainsail, where the leech is connected to the foot. The clew is attached to the boom.

- Tack - The tack is the lower front corner of the mainsail

- Head - The head is the top corner of the mainsail

Battens are horizontal sail reinforcers that flatten and stiffen the sail.

Telltales are small strings that show you whether your sail trim is correct. You'll find telltales on both your jib and mainsail.

The jib is the standard sized headsail on a Bermuda Sloop rig (which is the sail plan most modern sailboats use).