Yachting World

- Digital Edition

How (and why) wood is making a comeback in yacht building

- Rupert Holmes

- May 30, 2023

Rupert Holmes reports on latest developments in wooden yacht construction, and why this ancient material is being used for hi-tech contemporary design

Why would a naval architect and structural engineer used to working with cutting edge materials for America’s Cup teams, including INEOS Britannia , and companies like Airbus, be excited about working with wood?

“It’s quite simple for me,” says French designer Thomas Tison, “Modernity does not neglect where we all come from – on the contrary it makes the best of it. In a way a boat is a heritage, so to ignore wood would be to ignore the essence of yacht design and building.

“Carbon fibre is only an evolution from this heritage and reinstating wood as a modern material increases the number of options a naval architect has for creation and performance.”

Tison designed the stunning, contemporary 48ft offshore racer Elida which launched last year, and currently has a timber/epoxy 40ft high-end daysailer on the drawing board. To optimise Elida ’s weight and stiffness Tison tested three different timber and glue laminates at an Airbus facility. “What we found was very interesting,” he told me. “The existing data was 20 years old, but now we can carefully select the glue and timber, so the figures for our laminates were stiffer than predicted, with the sitka spruce an order of magnitude better than expected.”

Elida is built of diagonally planked sitka spruce covered with a 3mm mahogany veneer. Additional internal stiffening is provided by local layers of 200g carbon fibre. The result is a very stiff structure – projected forestay loads match those used on TP52s, yet the total weight of the 48ft hull shell is only 1,000kg.

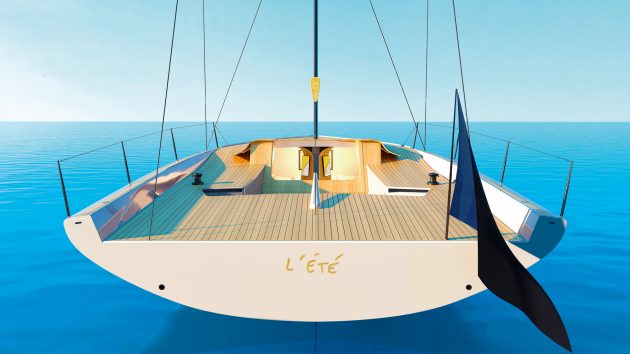

Tison’s next project is a very high end 40ft daysailer. Construction will be an evolution of Elida ’s, giving a strong and stiff structure that meets Category A requirements, yet total displacement is only 3,700kg. He also has a concept under way for a 45m superyacht built in a similar manner.

Outlier is a cold-molded custom 55-footer designed by Botin. Photo: Billy Black

Traditional skillset

The enthusiasm naval architects young and old have for wood/epoxy composite construction is striking. Many of today’s stand-out new designs on both sides of the Atlantic are built this way and it’s often the best option for one off builds and short production runs. Key advantages include stunning aesthetics, stiff, lightweight structures and excellent longevity.

Today British yard Spirit Yachts is perhaps the most well-known specialist in this form of construction and their wood-as-art concept is well documented, including the sculptural approach taken with the Spirit 111 Geist . However, examples of other yachts abound, including Rob Humphreys’ Tempus 90 superyacht. This was built in Turkey, which unlike many countries never lost its wooden-boat building industry. As a result plenty of yards today are familiar with working with epoxy/timber composites. And many other top-notch recent wooden yachts have been built there, ranging right up to superyacht size, including Andre Hoek’s PC Yacht range and a number of his Truly Classic designs.

Britain has its own strong tradition of wooden-built designs: the Elephant Boatyard on the River Hamble has a long history of building, and maintaining, timber/epoxy yachts, including the Barracuda 45 built for Bob Fisher in the late 1980s.

Wood was the medium successful IRC raceboat designer John Corby made his name with in the 1990s and 2000s. And it was the choice of one of the UK’s most successful yacht designers, Stephen Jones, for his own 46ft one-off Meteor , launched in 2006. She was built in Grimsby by Farrow and Chambers, which also built two cedar epoxy yachts for former Yachting World editor Andrew Bray.

On the other side of the Atlantic, several New England yards are active in building new custom and semi-custom yachts in wood/epoxy. Notable recent examples include the Lyman-Morse 46, Brooklin Boat Yard’s Jim Taylor-designed 44ft Equipoise , and the Botin custom 55-footer Outlier . A long list of other notable recent launches include Anna , a 65ft Stephens Waring design built by Lyman-Morse and launched in 2020.

The beauty of wood inside a hand-crafted Spirit. Photo: Paul Wyeth

Build techniques

UK-based designer Rob Humphreys has a long association with this build method, having designed his first vessel in wood in the late 1970s, followed by a string of others, from 22-footers to superyachts, over the following decades. Humphreys remains keen to design more: “The only thing that’s holding us back really is an issue of market education,” he told me.

The medium is often poorly understood, with few people realising the benefits and many assuming it has the same drawbacks as traditional timber construction, or that the technology hasn’t moved on since cold-moulded wooden boats of the 1960s. These were built with resorcinol glues that were originally developed in the early 1940s, but required considerable clamping pressure to create a reliable bond and couldn’t be used as a coating to protect timber.

The epoxy revolution, driven enthusiastically by brothers Meade, Joel, and Jan Gougeon in Michigan in the early 1970s, marked a turning point for boatbuilding. “They got chemists to reconfigure epoxy to be runny enough to saturate the wood rather like a varnish,” explains Stephen Jones.

Even though epoxy doesn’t penetrate deep below the surface of timber, it sticks so well that, unlike paint and varnish, it forms a genuine barrier that keeps water out of the timber in the long term. As a result these boats have potential to last as long as any fibreglass structure.

Lyman-Morse 46 hull completed and being turned outside the boat shed. Photo: Alison Langley/Lyman-Morse

There was another key advantage. “It could also be thickened as required for glueing and, most importantly, gap filling,” adds Jones. This significantly speeds up the build process. These vessels are generally inherently stiffer and lighter than conventionally built fibreglass yachts and it was a preferred build method for performance yachts before cored composites became reliable.

Meade Gougeon’s 35ft trimaran Adagio , launched in 1970, was the first large all epoxy bonded and sealed wooden boat built without the use of mechanical fasteners (and is still sailing on the Great Lakes over 40 years on). Three years later the brothers built the Ron Holland-designed 41ft IOR Two Tonner Golden Dazy , ahead of a slew of further designs including a 60ft trimaran for Phil Weld’s 1980 OSTAR single-handed transatlantic race , before race organisers imposed an upper size limit. Weld subsequently had the 50ft timber/epoxy tri Moxie built by Walter Greene, in which he won the OSTAR.

Over the years precise construction methods have varied, although all but a handful of boats are built with several layers of timber with the grain running in different directions to create a stiff structure. Some have a purely cold moulded construction, with larger boats often employing four or more layers laid at around 90° to each other. This creates a lightweight and stiff structure that can be protected from impact damage with epoxy and glass cloth. The Lyman-Morse 46, for instance, is built of four layers of vacuum glued Douglas fir and western red cedar.

Hand-built expertise at the Spirit yard in Suffolk. Photo: Spirit Yachts

Others start with a layer of narrow planks, termed strip planking. This had been a construction method long before the use of epoxy, but it became much more popular thanks to the development of the Speed Strip technique by Sunderland timber merchant Joseph Thompson & Co (now renamed NYTimber) with help from Farrow and Chambers. The planks have a loose tongue and groove profile, allowing them to neatly conform to the hull shape and giving space for thickened epoxy glue.

Speed Strip also eliminated the need for scarfs to be cut where planks are joined and reduced the number of mechanical fasteners needed. This reduced planking time by a quarter, and clean up and fairing time by 70%. An additional advantage, Jones says, is the “predominance of fore and aft timber strips/planks increases global hull stiffness – the ability of the hull to resist rig loads.”

Around the same time Humphreys was also working on ways to reduce build times. The hull of his H22 sportsboat, which was available as a flat-pack kit with CNC cut components, could be assembled from scratch in a few hours by one person. I know of 40ft offshore racing yachts that were planked up in a week.

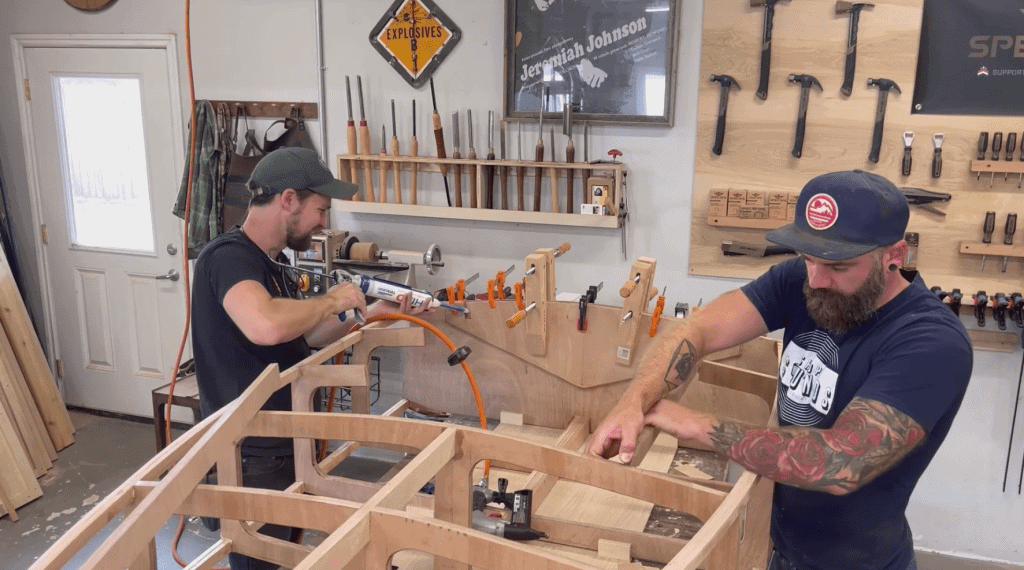

Strip planked boats can be built over laminated frames that become part of the final structure, and don’t require a mould that is subsequently discarded. These frames are surprisingly quick and easy to create – at Spirit Yachts, for instance, they’re assembled on full-size print outs of the boat’s plans laid over a plywood floor. This allows each piece of timber to be bent by hand into exactly the right shape and held in place using spikes driven into the floor. They’re then clamped together in situ while the epoxy cures.

The Lyman-Morse 46 interior shows off its timber construction, with plenty of white painted surfaces for an airy feel. Photo: Alison Langley/Lyman-Morse

Originally cedar was used for Speed Strip planks as it’s lightweight yet very resistant to rot, although other species with similar properties, including Douglas fir and sitka spruce, are also suitable. Typically two thinner outer layers of double-diagonal planking are added outside the strip planking.

In the case of Zest , our 36ft Rob Humphreys design built by Farrow and Chambers in 1992, this forms a 20mm-thick tri-axial construction with the grain of the timber oriented in three different directions. Larger yachts may have four or more layers outside the strip planking and a few boats have an additional transverse skin to help strengthen the area around the keel.

Impact protection

In all cases the whole lot is glued together and sealed from water ingress with epoxy. Therefore no more maintenance is needed than for a fibreglass hull and it will never succumb to osmosis.

Jim Taylor, designer of the 44ft Equipoise and 50ft Rascal , both recently built by Brooklin Boat Yard in Maine, says that in North America this construction is likely to be referred to as cold moulded, with the term referring to the outer layers, rather than the inner skin of strip planks.

Modern wooden builds created using latest CAD at Spirit Yachts. Photo: Spirit Yachts

Equipoise was built with a first layer of fore-and-aft tongue and groove larch planking which is epoxy bonded to the laminated keel, keel floors, bulkheads and ring frames. Outside of that two layers of diagonal 3/16in (5mm) paulonia were vacuum bagged at +/-45° to the initial planking. Then a further layer of tongue and groove larch was laminated over the paulonia, again in a fore and aft orientation. Outside that is a protective layer of epoxy/glass. Displacement is little more than six tonnes, despite an unusually large 44% ballast ratio, allowing a large rig without the drawbacks of excessive draught.

“There is a whole lot to like about this type of construction,” Taylor says. “The approach is cost effective and the result is extremely attractive on many levels. The boats are light, strong, tough, quiet and well insulated thermally. A bright finished inside skin can be integrated into an especially elegant interior, the construction materials are environmentally sustainable, and there’s not a lot of waste. They’re not as light as carbon skins over lightweight core, but they are much more liveable and not nearly as fragile or as expensive.”

The outer glass/epoxy sheathing can vary from light cloth for impact protection, through to heavier laminates that add structural strength in high load areas such as around the keel. A few boats have glass only outside, rather than additional layers of timber, but these heavier laminates need more work and filler to create a fair surface.

Carbon stiffening for Elida. Photo: Emeric Jezequel

Of course, if the outer sheathing is punctured, then it will need to be repaired quickly, but a quick application of epoxy filler is all that’s needed until a neat long-term repair can be made.

Developments and refinements over time include vacuum bagging the various layers of timber together, along with the external protective layers of glass cloth. At the high end carbon reinforcement is increasingly used strategically to add further stiffness where necessary, without a significant weight penalty.

Elida ’s varnished topsides look stunning, while those of the 1987 Humphreys-designed Apriori and 1988-built Old Mother Gun of 1988 still look great. There’s therefore a huge temptation for anyone building a wooden yacht to opt for similar finishes. However, it’s important to note in these cases the epoxy needs a more traditional varnish for UV protection and that can require a lot of maintenance. On the other hand, today’s polyurethane paints can last up to a decade in dark colours and Meteor ’s original white paint from 2006 still looks almost new.

L’Été is a new 40ft daysailer design by Thomas Tison.

Modern look

On the other hand, varnished bright work on deck and coachroof sides are subject to less wear and tear than topsides. Jones says these are easy to prep for varnishing if designed with simple surfaces without fiddly detail. The cleaner style of modern classic deck structures also reduces water retention, so surfaces dry quickly. “It can still look the part but becomes less onerous to keep,” says Jones.

Below decks it’s easy to fall into a trap of showing off so much natural timber that the interior becomes dark; a strategic mix of white painted panels and clear timber finishes gives a much brighter result. The Spirit 72 , for instance, has satin painted panels and a carefully planned LED lighting system to enhance the warmth of the natural timber.

The Spirit 111 has a sculptural cockpit and interior. Photo: Spirit Yachts

Hull windows are possible and, even if maintaining a classic external appearance is a priority, it’s possible to allow a lot of light in from the deck. Spirit Yachts’ trademark fantail window is an excellent example of this.

Alternatively, interiors can be absolutely contemporary in style, as seen in RM Yachts’ 29-43ft range of plywood/epoxy performance cruisers. Plywood also offers excellent stiffness in relation to weight and is an ideal medium for today’s chined hull shapes. At RM all the pieces for an entire boat are delivered on pallets, ready for immediate assembly. Hulls are built over frames of substantial chipboard set up on jigs. Assembling a hull is therefore a straightforward process that doesn’t require a full mould.

The Ace 30 scow bow short-handed IRC raceboat also employs plywood/epoxy construction. It’s an approach the builder says considerably reduces the carbon footprint of building each boat.

Matt Newland of Swallow Yachts tells me their Whisper 300 retro-style planing motor cruiser has demonstrated that at sizes above 30ft an epoxy/timber construction can compete directly on labour hours with conventional fibreglass boatbuilding. The company’s next model, the Bay Cruiser 32, will be a traditionally styled, but very lightweight and quick, 32ft trailerable weekender made of clinker-style plywood and epoxy.

Other forthcoming projects include a range of 45-70ft modern classics by Stephen Jones and illustrator/designer Jonty Sherwill that will be built by the Elephant Boatyard.

These boats will also be more sustainable than their contemporaries built using conventional glass fibre or more advanced composites. The quantity of epoxy used for the build is small and bio-sourced resins can be used without the requirement for a full size mould. The result is that the carbon footprint associated with building the Ace 30, for instance is 1.9 tonnes, but would be more than three times that value for a boat of conventional construction, even before accounting for building the moulds.

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the world’s leading magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have inspirational adventures and practical features to help you realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge with a subscription delivered to your door. See our latest offers and save at least 30% off the cover price.

Refastening a Wooden Hull - Season 4, Episode 1 Now Available!

Wood Selection: Choosing Boat Lumber

The original print version of this quide can be viewed as a PDF or purchased from the WoodenBoat Store.

W ooden boat building is different from any other form of woodworking. It requires curves and angles rarely found in furniture and house construction. Boats are structures that move. Because a boat spends much of its life in water, the wood used to build it must have certain properties that give it sufficient strength, make it resistant to rot, and provide resiliency when used in conjunction with fastenings, adhesives, and day-to-day use. So, as you begin to look at boatbuilding wood, there are certain things you’ll need to know.

In this issue of Getting Started, we’ll examine important characteristics of wood, look at some of the wood species and plywood types used in boatbuilding, and give you some pointers on how to create a stock list. This article is limited to wood selection, so you won’t see processes such as milling, machining, or working wood covered here. This overview, we hope, will help you select the best material for your project and help you to get the most out of every board foot.

Wood Basics

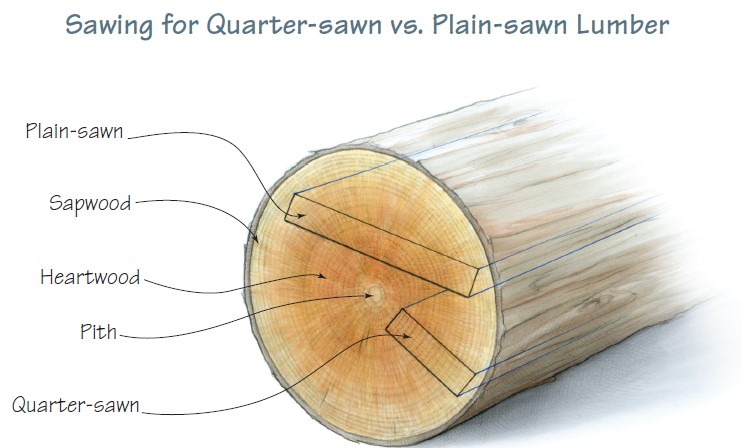

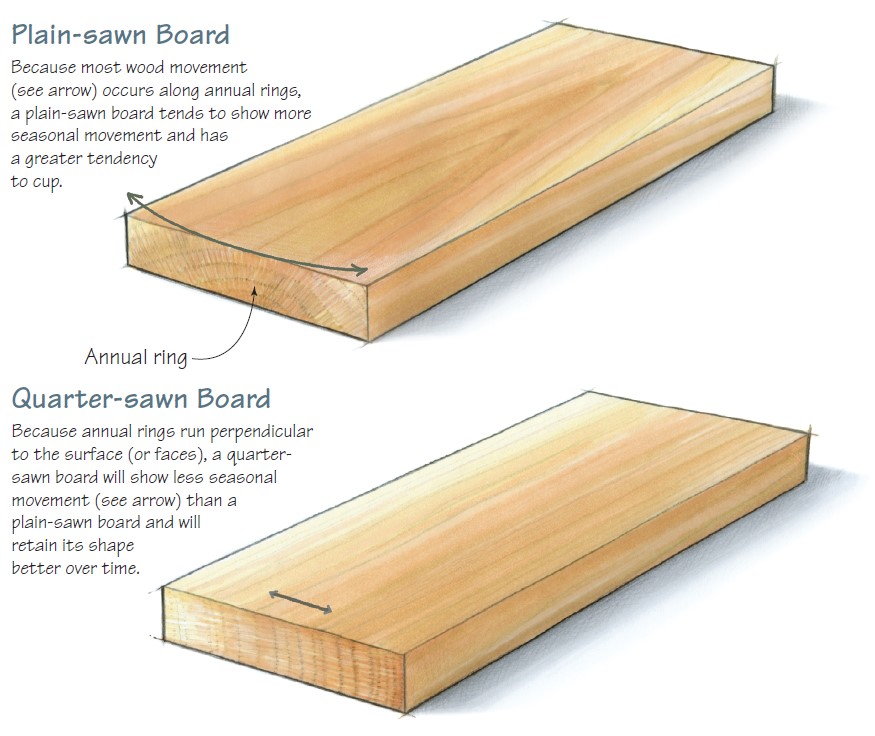

W hen selecting wood, it’s important to consider dimensional stability. Dimensional stability refers to how much a board shrinks or swells. One way that sawyers can help assure some level of dimensional stability is by taking cuts in the log that best utilize its growth-ring pattern for minimizing shrinkage and swelling.

What to Look for in Boat Lumber

Quarter-sawn lumber will have good dimensional stability across its face. It is usually considered the prime cut and, as such, costs more than the other cuts. Plain-sawn (or flatsawn) wood will have a tendency to cup and, over time, it will appear as if growth rings are trying to flatten out. Quarter-sawn wood is good to have in some boatbuilding applications, such as planking below the waterline, where swings in shrinkage and swelling are greater than they are on the remainder of the hull. Plain-sawn wood is suitable for planking and other components in small boats. Heartwood (the older part of the tree) is often more durable than sapwood (the outer rings in the living tree). Sapwood of any species is considered non-durable. Some boatbuilders shy away from using sapwood, others do not. Personally, I am less inclined to use it unless I can place it well above the waterline.

More Terminology

H ere are some characteristics and terms commonly used when dealing with boatbuilding lumber; the first four have to do with warping.

Bow—Curve along the face of a board from end to end, like a rocker at the base of a rocking chair.

Crook—The end-to-end curve (warp) along a board’s edge. Not to be confused with this form of warp is the term crook timber, also known as compass timber (and often referred to as “a crook”), which is sawn from the roots and branch crotches of trees. The natural curvature of crook timber makes strong and beautiful stems, breasthooks, and quarter knees.

Cup or Cupping—Curve along the width of a board from side to side. Cupping is the result of uneven drying. Using even slightly cupped wood on a table saw heightens the danger of the operation because it can lead to a pinched blade and kick-back. If cupped wood must be used, I favor cutting with a bandsaw, as it is less likely to cause harm. When cutting cupped wood on a bandsaw, be sure to place the board cupped-side-down on the worktable (as a frown) for better stability while you work.

Twist—An uneven warping that makes the board appear to be spiraling. This defect is a dangerous one to mill, a difficult one to correct, and should be avoided if possible.

Checks or Checking—Cracks in the wood, usually found at board ends and sometimes found in the middle of the board. Checking can be a result of uneven drying, living tree shakes, or mishandling (dropping). Look carefully at boards that have checks. While checks may appear to be only a few inches long (and many are), they might indicate a major weakness along the board’s length.

Pitch Pocket—A pitch pocket is an opening between the growth rings that now holds, or did hold, resin.

Live Knot— Live knots (also known as tight or red knots) are so named because they were alive when the tree was harvested. They are more firmly attached to the board than dead knots. Since they usually are not rotten, they can sometimes be left alone rather than drilled out and plugged.

Dead Knot, Loose Knot, Black Knot— Dead, loose, or black knots are from a branch that was dead at the time of harvest. These are dark, rotten, and usually loose or easy to loosen and should be removed. They’ll leave a dark hole that should be reamed free of residue and then plugged.

Four-quarter (4/4)—A way of describing stock according to the number of “quarters” or quarter-inches in its thickness. Boards that are 1″ thick are referred to as four-quarter (4/4) stock. Five-quarter (5/4) stock is 11⁄4″ thick; six-quarter (6/4) stock is 1 1⁄2″ thick; eight-quarter (8/4) lumber is 2″ thick. Expect these to be rough-sawn dimensions, especially if wood is purchased from a lumberyard. Finished wood denoted as 4/4 will actually be somewhat thinner than an inch. So, if you need wood that is truly 1″ thick, you’ll need to buy rough stock that is 5/4.

Rough or Rough-sawn Lumber—Wood that has not yet been planed to finished thickness.

Finished Thickness—Wood that has been planed to its final thickness and is ready for the project at hand.

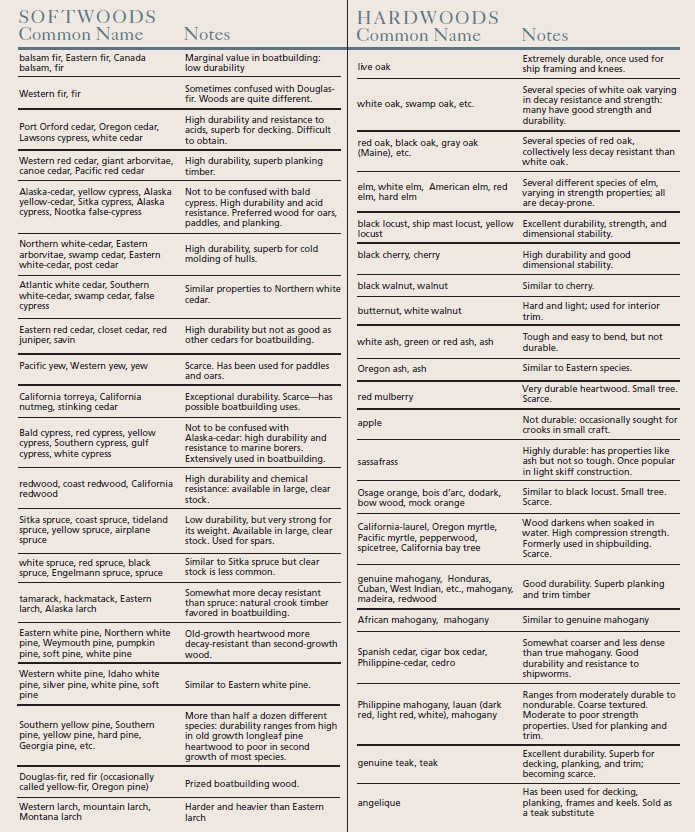

Wood Species

D r. Richard Jagels, professor of forest biology at the University of Maine in Orono and a regular contributor to WoodenBoat , prepared the following list of wood species that are often used in boatbuilding. It should be noted that the advent of strip-building has opened new frontiers to small-boat builders. Often used to construct canoes and kayaks, this process usually includes gluing together long, thin strips of wood on a mold into a hull shape and then encapsulating it with fiberglass cloth and epoxy. Woods such as walnut, basswood, and a variety of other species that are not traditionally thought of as boatbuilding (or at least hull-building) woods are now regularly used for strip-planking. They offer new options and color choices for small-boat construction.

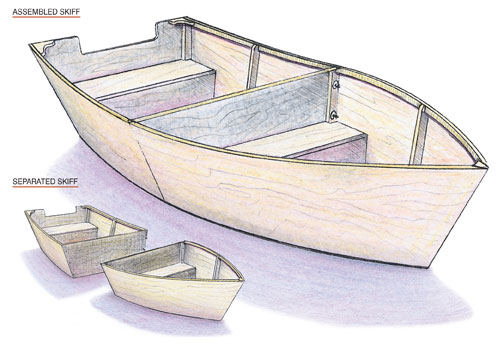

P lywood continues to gain in popularity among boatbuilders, especially those who build small boats. Chief among the reasons are its dimensional stability and its availability. It is also becoming increasingly difficult to find natural wood that is wide enough for some planking. For example, in building a traditional skiff, it is not uncommon to need a 14″ – wide board for the garboard (lowermost) strake. Also, plywood is more split-resistant, often outperforming even a properly steamed natural plank.

Some plywood is not suitable for use in a marine environment. To assure that yours is, you’ll need to look at its rating.

One basic classification to look for is B.S. 1088. The B.S. stands for “British Standard”—an acknowledged standard-setting entity. The “1088” is their best-known designation for marine plywood that is suitable for small-boat and pleasure-boat building. It is manufactured with waterproof glue and has a very limited number of small voids. An additional assurance that your plywood meets these standards comes from Lloyd’s Register. The Lloyd’s sticker on the sheet indicates that, in addition to meeting the British Standard, the manufacturers have placed themselves under the scrutiny of Lloyd’s and have agreed to meet with their standards. B.S. 1088 with the Lloyd’s sticker is more costly than the rest—but many builders feel that it’s worth it. When you consider how little the cost of materials is in the scheme of building a boat (time in labor is the greatest expense), I would agree with them. When you shop for plywood, make sure that it meets B.S. 1088 or a comparable standard.

Another factor to consider is the boat’s intended use. Our technical projects manager and resident boatbuilder here at WoodenBoat, Tom Hill, says, “When I build a small boat that needs to be lightweight but can be stored in a garage, I use okoume. It is easy to work and it takes paint well. When weight is less of a concern and I need the boat to be highly rot and abrasion resistant, like when I’m building for an owner who plans to moor his boat all season, then I’ll use sapele.”

When looking for marine plywood, it’s important to ask questions. Reputable dealers will help you, even if you don’t wind up buying from them. To learn more about marine plywood, I encourage you to read Chris Kulczycki’s article on the subject in WB No. 174.

Calculating Board Footage

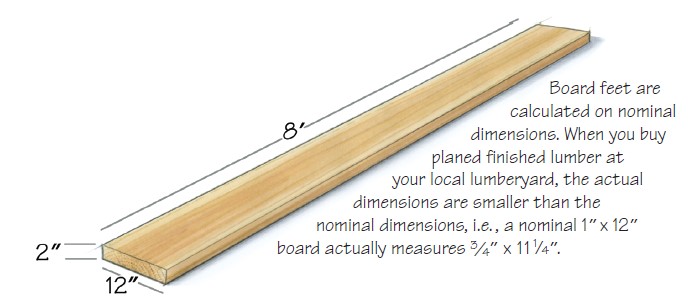

B oard feet” is a way to express lumber volume. One board foot is equal to 144 cubic inches of wood. To find board footage of an amount of wood, we multiply the thickness (in inches) x the width (in inches) x the length (in inches) and divide it by 144 .

So, for our 1 BF we have: 1″ x 12″ x 12″ = 144 cubic inches 144 cubic inches /144 = 1 BF

Now let’s look at a more complex scenario. Here we have a board that is 2″ thick x 12″ wide x 8′ long. First, let’s convert the length measurement into inches. Now we have: 2″ x 12″ x (8′ x 12″ [per foot]) = 2,304 cubic inches then 2, 304 cubic inches /144 = 16 BF

Making a Stock List

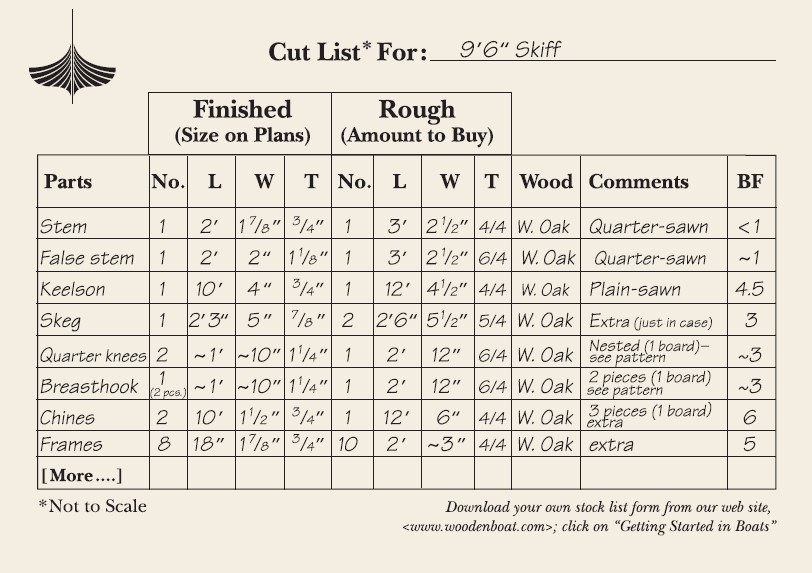

W hether you plan to purchase your wood or go out and harvest it yourself, it’s a good idea to begin your planning by making a stock list (aka: cut list). It may take some time, but in the long run having an accurate stock list will be a big help in estimating costs, and it will guide you in your selection of stock.

The chart has spaces for the individual pieces, the number of pieces needed, their finished dimensions, rough dimensions, wood type (species or plywood type), comments (such as notes or sources), and board feet (BF). You can easily make a chart by hand or on your computer, or you can download one from our web site <www. woodenboat.com> (click on “Getting Started in Boats”).

Begin by looking at your plan. List the names of each piece in the stock list. Some people like to list items according to their building sequence. I prefer to list them according to wood species used. Then, put in the finished dimensions of each piece. Depending upon the level of detail given in your plan, you may need to do some “guesstimating.”

Details such as finished plank lengths can be difficult to pick up from the plan since they are either foreshortened or don’t go in a straight line in every view. Planking presents other special challenges, too. The forward part of the plank may be wider than the aft section. This is often the case with the garboard plank on a traditional skiff. This type of plank may be built out of two boards of different widths. If you choose to do this, make a note of it on the stock list and account for the added length that will be needed to join the two boards together with a scarf joint (a long, tapered joint between two long pieces of wood). Once you have determined the overall finished lengths of your planks and plank pieces, add two to three feet to the overall hull length (rough dimensions) to allow for bending and clamping. Do the same for other long components.

Also note which pieces, such as quarter knees, can be nested (almost like interlocking pieces) or configured around a knot and cut from the same board. I find it helpful to make a sketch of how these could be laid out and what type of board and grain pattern is best.

Finally, in tallying your stock list, you’ll need to add extra BF to account for waste and defects. Are you sitting down? For planking, especially if your stock is live-edged (with the bark still on it), has sapwood, and a lot of defects, plan on over-buying by as much as 100%. For other pieces, plan on buying 30–50% more wood than you think you’ll need.

Locating and Storing Wood

Locating wood—Finding wood for boatbuilding can be a challenge, especially for people who live far from where it is harvested. Unlike the species needed for house construction or furniture making, boatbuilding woods are rarely carried by lumberyards. Get to know a local sawyer, if possible. Lumberyards and big-box stores can be a good place to buy interior or exterior grade plywood (non-marine use), or medium- density fiberboard (MDF) for building jigs and molds. Occasionally, you can even find wood for components like thwarts.

Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that one excellent source for locating boatbuilding wood and specialty lumberyards is the classified ad section of the magazine you are now reading.

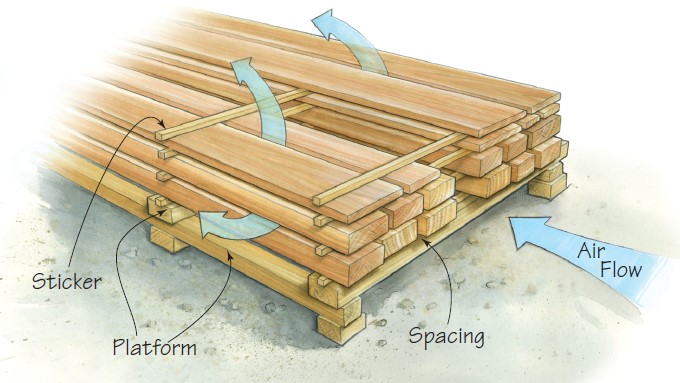

Storage—The cover photograph for this issue of Getting Started shows how we store white cedar planking stock at WoodenBoat School here in Brooklin. This idea came to us from Harry Bryan, a popular instructor at the WoodenBoat School and a contributing editor to this magazine. While a practical and ingenious idea, most people don’t have the room or the need for this much lumber. The illustration above depicts a method that will work for just about anyone.

Distribute your lumber by weight. Place the largest, thickest pieces at the bottom of the stack. Don’t forget to place stickers under the bottom-most pieces. Make sure that there is at least a finger’s-worth of space between boards that are placed next to one another. Follow this procedure as you place each (progressively lighter) layer of wood on the stack.

Whether your wood is home-harvested or an online purchase, the quest to find boatbuilding lumber shouldn’t feel like a trip to the woodshed. We hope that we have provided you with some new insights so that you’ll know what to look for (and look out for) when selecting wood for your next project.

Karen Wales is associate editor of WoodenBoat. She thanks Dick Jagels for his contributions to this article.

Further reading: Considered the preeminent source in the United States, “Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material” from the USDA Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin.

Small Boat Decks

A blacksmithing primer, subscribe for full access.

Flipbooks are available to paid subscribers only. Subscribe now or log in for access.

Practical Boat Owner

- Digital edition

Boat wood: a complete guide for yacht owners

- lyndonmarch

- November 2, 2023

Boatbuilder and finisher Lyndon March explains which types of wood work best for different repairs and modifications on board

Whether you’re building a boat from scratch or making repairs, knowing which wood will work best for the job is essential. Credit: Dmitriy Shironosov/Alamy Credit: Dmitriy Shironosov/Alamy

Repairs, replacements and restorations are very much part and parcel of boat ownership.

At some point most of us will have to tackle a small, niggling woodwork repair ourselves, or undertake a larger-scale project.

However, are you making the correct choices when it comes to choosing the timber to use?

Like most items associated with boats, there is not a definitive right or wrong approach, but guidance is useful.

We often think of stout working boats as built of larch or oak and finer yachts dripping in teak and mahogany.

This is not always the golden rule though.

You may be able to source reclaimed teak to make repairs to small areas of deck

It’s worth keeping in mind the three key points when looking for the right wood for your project: durability, movement and structural integrity.

If your choice in material is informed by these golden rules you can make smart decisions and execute a lasting repair or update to your vessel.

Most commonly it’s the high-impact areas of a boat that require renewing, like grab rails, rubbing strakes and toe rails.

Exposed, vulnerable and rarely finished with more than a simple oil, these are the parts of the vessel that take a pounding during the season, doing very little for the longevity of the timber.

For most craft manufactured pre-1990, these areas will almost certainly be made of teak.

Owners are advised to look after teak with careful cleaning to increase its life, especially as teak is scarce.

Grab rails and toe rails are often made of teak, so look after them. Credit: William Payne Photography

However, if it does need replacing, you may be able to grab a bargain on the second-hand market, given the small amount of wood you’re likely to need.

Teak is a wonderful material, with an ability to weather gently and an almost self-oiling quality.

It also fits all of our key points – scoring highly on durability and movement as well as structural integrity.

Teak can also be used almost anywhere in a vessel; as demonstrated in my own 1901 rowing dinghy which is entirely built of teak.

Fortunately, but not without some hunting around, there are small quantities of teak still lurking in timber yards around the country, and certain specialists such as Trinity Marine carry stocks of reclaimed teak; however, it is expensive and requires some careful machining to minimise wastage.

There are big challenges in sourcing teak which is legal and ecologically sustainable.

Boat wood: Alternatives to teak

Being realistic about the affordability of the wonderful oily teak forces us to look within the mahogany family or iroko.

Both meet our three golden rules; with iroko giving us a bit more structural integrity and providing much more durability in the weather if left uncoated or oil finished.

Khaya, sapele and utile mahoganies will easily hold up as toe rails and rubbing strakes and, much like iroko, give us wonderful grain results but really require a varnish to add protection and longevity.

A future world without the availability of teak forces us to look at other areas of our vessels that might need repairs; decks, cockpit gratings , hatches and skylights.

Mahogany needs varnishing in order to protect the wood and increase longevity

If these are teak, then it pays to look after them.

Those of us fortunate enough not to have a traditional laid deck might still have deck planking or at least deck coverings.

It’s not uncommon for vessels to have a teak-clad deck or at least some teak trim, pulpit perches or cockpit locker lids.

Years of enthusiastic deck scrubbing, clumsy feet, or gentle sanding often leave teak decks in a bad state of repair, with the screw plugs barely hanging on for life.

For smaller sections, you may be able to hunt down some elusive teak but for bigger areas of decking, you’ll need to look for an alternative.

Iroko can be matched to existing teak, which makes it ideal for decking. Credit: Hazel McCabe

Iroko could be the perfect alternative to teak. Unfortunately, it’s not particularly nice to work with and some people have suffered allergic reactions to it, so it’s advisable to don personal protective equipment (PPE) when working with iroko.

Iroko can, however, provide you with a teak-style of deck that should give a hardly noticeable match to existing teak.

It can be left to weather or be oiled and varnished with stunning results.

If you’re replacing a large area, or laying all new decking , I’d recommend taking some inspiration from the working boat scene.

Douglas fir or larch are easy to machine and suitable for glueing to a subdeck.

They meet nearly all of the three golden rules, and age to a lovely even-weather grey colour, much like untreated teak.

Both are also soft underfoot for those barefoot sailors among us.

But they do have one disadvantage: neither last as well as teak, with maybe a 10- to 15-year lifespan depending on how well the wood has been cared for.

Keeping boat wood healthy

On a well-kept and regularly sailed vessel, it’s unusual to find fungal issues on deck timbers and fittings – a regular dousing of salt water tends to keep this problem at bay.

Deck fixtures, however, tend to suffer from wearing out or damage and occasionally UV-related issues.

The less saturated and inaccessible sections of our boats can play host to fungi; even wonderfully oiled teak and varnished mahogany can be no match for a lack of ventilation.

Mast foots, cockpit lockers, cabin soles and interior joinery all suffer.

Mostly it’s cost-effective to replace like for like.

Most vessels have been fitted out with hardwood-trimmed plywood panels bonded together and then bonded to the vessel.

In areas of little ventilation, wood can rot. It is usually best to replace like for like

This is still a great approach, as plywood is simple to bond and use, as well as providing structural integrity, movement and durability.

It also means that huge amounts of extra internal weight are not being added down below; important for a well-balanced boat.

We shouldn’t just limit ourselves to painted white plywood with hardwood trim.

The replacement of interior joinery gives us a chance to amplify the space, and there are lots of kits and tutorials on how to add a veneer or carbon wrap to your plywood.

No matter how large or small the repair is, you should consider ventilation in the area where the wood is being replaced.

Look at coating the edges of the plywood and investing in marine-grade quality plywood.

Continues below…

Best boat varnish: 7 top options for gleaming woodwork

Few things are as quintessential to the archetypal sailboat as gleaming, iridescent woodwork that is indicative of a recent coat…

Replacing a rotten companionway step

James Wood gets to grips with epoxy when repairing a rotten step support on Maximus's companionway

Teak alternatives: How to make your decks look as good as the real thing

However, according to a recent report by the Environment Investigation Agency, there are grave questions over the sustainability and sourcing…

How to build a boat: Essential guide to building your first kit boat

You don’t have to be a boatbuilder to learn how to build a boat, argue Roger Nadin and Polly Robinson.…

While replacing the interior joinery, it’s worth thinking about how to reinvigorate the cabin and cockpit sole.

Of course, there’s nothing wrong with using a faced plywood subsole, but there might be an opportunity here to add a much harder and better-wearing cabin sole that is more appropriate for the rigours of life at sea.

Soles are often thinly veneered and satin vanished, which never seem to last past the first week of the season.

A more solid solution is beaded-edged Douglas fir or larch, which can look wonderful down below.

They can also be laid over a subfloor in your desired thickness and if you need it watertight, the beaded edge can be swapped for a caulked edge.

Allowing this to grey and develop a more natural look will not only reduce your maintenance but give you a harder-wearing, practical finish.

If you do end up dropping a bottle of red wine all can be fixed with some sandpaper and the process of time.

Best wood for masts

There is a section of the vessel often overlooked. We winterise our engines, boat covers go on and the cushions come ashore , then we think about our mast; ashore in the shed or utilised as a ridge pole, then stuck in the mast step or tabernacle for the rest of the season.

Owners of aluminium mast can fear not, but for anyone sporting a shiny wooden one it’s hardly unsurprising we often find some softer spots around the ends.

There is a lot to be said for the proper coating of spars but what do you do if your gaff, boom, or bowsprit is beyond repair?

Mostly our spars are made from softwood; on very unusual occasions, you might find a hardwood bumkin or bowsprit , but these are unusual.

When selecting timber for spars, the durability and structural integrity of the wood must be considered, but the most important factor is movement.

Wooden masts are generally made from softwoods, like larch, Douglas fir or sitka spruce. Credit Graham Snook/YM

Main masts, bowsprits and bumkins tend to require less twist and flex than gaffs , booms or the extremely endangered wooden spinnaker poles.

While I have seen smaller dinghies sporting oak, iroko and even ash for these spars, they’re not recommended unless you have a particular vessel requirement.

Larch is often used in larger working craft for these spars and if constructing a solid spar, this might actually turn out to be a good choice for a new home-crafted main mast.

As the availability of sitka spruce has dwindled and is now only available through very specialist suppliers such as Robbins Timber or Stones Boatyard, a discerning mast builder should look at Douglas fir, which gives movement, structural integrity and durability.

This solid wood is excellent for glued construction and is also easy to work with – important if this is your first foray into wooden mast building.

There is some lovely slow-grown, tight-grained timber on the market currently and it can be sourced in the UK.

Boat wood for strong steering

Fortunately or not, many boat owners will only have to varnish and care for their wooden tiller.

Again, there are plenty of options, but it is worth thinking about what you require – durability, integrity and movement – and also think about the aesthetics.

Iroko and oak are strong and durable and can stand the weather uncoated, whereas Douglas fir or mahogany tillers will need coating.

Ash is the preferred choice for a tiller – like on this Hallberg-Rassy 29 – as it’s strong and not too heavy

Unless you manage to find a grown shape in oak, all of the above will require laminating so the tiller doesn’t have lots of short grain which results in a weak construction.

Traditionally, tillers were always made of ash; this is a wonderful timber that is very strong but not too heavy, ideal for balancing transom-hung rudders .

However, ash is not readily available.

Whatever wood you use to build your tiller, it is a good idea to make a spare to store down below in case of an emergency.

Build solid

Timber selection isn’t just important for repairs and replacement, it also has huge implications for the construction of new wooden vessels.

As traditionally used timbers, such as grown oak and elm, have all but disappeared from the market, many traditional boatbuilders are now having to think far outside the box.

Centrelines were traditionally built in oak, but now iroko, opepe and even purple heart are all being used in its place.

These woods have proven longevity, having been used during the early restorations of classic boats which are still sailing regularly today.

For sawn and steamed timbers, oak is still the most popular.

Some builders are using the laminate construction of iroko or mahogany for building larger craft, but this tends to be for ring frame constructions and combines the deck beam into this process.

Carbon compatible

Companies such as Spirit Yachts have really pushed this a step further by combining carbon fibre alongside this timber construction; a great way to add strength to a boat.

Transoms, coamings and other brightwork still, for the time being, carry the trends seen over the centuries, with mahogany or teak being favoured, but this could change as the availability of timber changes.

Possibly, we will see more of a workboat look coming in, with these surfaces becoming painted and less exotic, but still durable.

The biggest challenge facing the modern boatbuilder is sourcing good quality timber for hull planking.

The centreline of the Spirit 111 was made using Douglas fir; a stainless steel space frame on the middle ring frames adds stiffness. Credit: Mike Bowden/Spirit Yachts

The wood needs to provide the length needed, without forcing lots of unnecessary scarfing planks and has to allow steaming and the twist of tricky underwater profiles.

The traditional boat scene soldiers on with oak and larch in this regard, and the vessels built at Working Sail in Cornwall show what can be achieved.

Other builders are using alternatives though.

The Falmouth Pilot Cutter, Pellew , built by Working Sail, has oak frames and planking. Credit: James Stewart

Dan and Barry Tester rebuilt smack hulls from iroko, while Gerard Swift used Khaya mahogany to plank his skiff Mersea Native in 2000, which is still sailing today. If you can source larch, it’s a good middle ground between all of these options.

The reality of timber availability will soon catch up with us all, eventually limiting the options for amateurs and professionals alike.

In the meantime, however, if you remember the three golden rules and select a timber suited to your needs and requirements, you shouldn’t go too far wrong.

The best boat wood for the job

Centreline timbers.

Purpleheart is durable, water-resistant and reacts well with changes in humidity, making it ideal for use in the centreline of a boat. Credit: Getty

The centreline of a vessel requires a timber that’s strong, durable and long lasting.

- Pros: strong traditional choice, often allowing the option of grown pieces with stem construction.

- Cons: lengths of long, clear timber are hard to find. Green timber is prone to movement as it seasons. Expensive.

- Pros: stable timber available in long lengths, often able to provide wide boards which is important when looking at constructing hogs. Represents relative value for money. Works well for lamination when creating curved stems or stern posts.

- Cons: often hit and miss in terms of quality.

- Pros: stable timber available in long lengths. Reasonably priced, heavy timber.

- Cons: can check heavily in sunshine; if working outside keep it covered or apply a priming coat. Can occasionally reject coatings and sealants, so it is worth researching which coatings are successful.

Purpleheart

- Pros: durable, insect and water-resistant. Purpleheart also reacts well to constant temperature and humidity changes.

- Cons: harder timber can be unkind to tools and tricky to work with.

Douglas fir

- Pros: long lengths of large, clear timber available, can provide great options when looking for sustainable-sourced timber. Much kinder on tools.

- Cons: not as durable as hardwood for a keel but not a bad choice for internal keelsons and deadwoods.

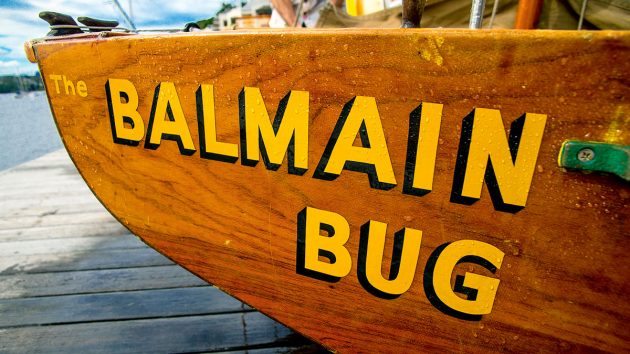

Most woods used for transoms – such as surian on this Balmain Bug, will need plenty of coats of varnish. Credit: Crosbie Lorimer

For those of us sporting neat canoe sterns or long sweeping counters, this isn’t much of a concern, but for others, transom timber choice is vital.

It’s also often required to take a coat or nine of varnish.

- Pros: beautiful varnished finish. Responds well to steaming and lamination. Long lasting and rot resistant.

- Cons: expensive and scarce.

- Pros: nice varnished finish. Responds well to steaming and lamination. Long lasting, wide-boards available.

- Cons: hit and miss in terms of quality. Often hard to purchase large quantities of colour matched boards.

- Pros: beautiful varnished finish. Responds well to steaming and lamination. Colour matched boards available.

- Cons: needs to be well cared for to ensure longevity.

Hardwood veneers

- Pros: various options for varnished finishes. Wide. Used with glues and hidden fastenings, it can provide stunning results.

- Cons: can be tricky to work with as easily damaged and requires thoughtful preparation before and during coatings. Needs to be placed on strong foundations.

Floors and frames

Iroko is ideal for lamination. Credit: Getty

An important structural element of any vessel, while many modern alternatives of carbon and laminate exist, the more traditional choices are limited.

It’s important to think about short grain when looking for curved pieces.

- Pros: the only single piece timber if you require any shape. Strong and reliable.

- Cons: expensive. Grown pieces are becoming harder to find.

- Pros: strong, good for lamination and steams well.

- Cons: grain short for curves.

Oak bends and steams well, making it ideal for planking, although it is expensive to buy. Credit: Ilkka Ranta/Alamy Stock Photo

Choosing a suitable planking material is as important as it helps to determine the overall weight and strength of the vessel.

Consider what you want the planks to do: Are there tight curves? Lots of wear? Or is it all about grams of weight and dry sailing?

- Pros: a traditionalist’s choice when paired with oak. Available in long lengths. Strong and long lasting. Steams and bends well.

- Cons: wider boards becoming trickier to find. Beware of knots and sap and imitation pines.

- Pros: fantastic strong choice. Can be vanished as a topside finish. Steams and bends well. Wider boards available. Thicker boards can be cut to provide split planks and colour match for a varnished finish.

- Cons: prone to cracking or splitting when fitting or fixing. Check for rot and sap when purchasing wider boards.

- Pros: wonderful strong timber. Durable and rot resistant.

- Cons : limited on width of boards. Doesn’t bend or steam particularly easily, but can be done. Prone to checking and cracking under UV, even through coatings.

- Pros: strong and hard wearing. Steams well.

- Cons: can suffer becoming wet and dry, so needs one constant state – better being used below the water line. Hard to find outside of reclaimed stock.

- Pros: strong timber. Bends and steams well.

- Cons: can react to fastenings, and suffer UV damage.

- Pros: lightweight and easy to work with.

- Cons: lightweight timber, expensive and doesn’t last as long as other choices of timber.

- Pros: bends and steams well, making it perfect for awkward shapes.

- Cons: expensive. Difficult to source wide and long boards. Prefers to be in a constant state of temperature and humidity, so it is better used below the waterline.

- Pros: varnishes well for topside finish. Bends and stems well. Doesn’t react with fastenings.

- Cons: doesn’t always have the longevity of other timber. Doesn’t stand up well to freshwater damage.

Boatbuilders, like Spirit Yachts, are now using Douglas fir for decking. Credit: Jessie Rogers

When choosing wood for decking, think not only about strength and waterproofing, but the overall looks and aesthetics it’ll bring.

- Pros: wonderful traditional choice that both weathers well and lasts. Works well over a subdeck. Solid planks.

- Cons: don’t over-scrub and wash with a brush. Expensive and harder to find.

- Pros: great alternative to teak. Works well over a subdeck. Solid planks. Wide boards are available.

- Cons: doesn’t last as long as teak. Not as soft under barefoot. When machining large amounts and creating dust, it is highly toxic.

- Pros: cheaper alternative to hardwood. Weathers to a beautiful silver. Lays well over a subfloor and solid planks.

- Cons: soft and can be easily damaged.

Rubbing strakes and toe rails

Hardwood, like teak, is best for toe rails. Credit: Mike Taylor

This is a high impact area, rarely varnished and undercoated. If you can, look for a hardwood option here.

- Pros: hard wearing and weathers well. Rot resistant.

- Cons: expensive, hard to find.

- Pros: great alternative to teak. Wide boards available which is handy for tall toe rails.

- Cons: can be tricky to steam small section round bends. Highly toxic.

- Pros: varnishes well for topside finish. Bends and stems well. Doesn’t react with fastenings. Ages wonderfully under varnish layers.

- Cons: doesn’t stand up well to freshwater damage.

- Pros: strong timber. Bends and steams well. Looks better when scaled up in large sizes.

- Cons: can react to fastenings, and can suffer UV damage. Expensive choice. Can reject vanishes and expoxies.

- Pros: cheaper alternative to hardwood. Weathers to a beautiful silver colour.

- Cons: soft and easily damaged. Can soak up the varnish coats.

Cockpit gratings

Teak is highly rot resistant, making it ideal for a cockpit grate . Credit: Katy Stickland

- Pros: hard wearing, and weathers well. Highly rot resistant.

- Pros: great alternative to teak.

- Cons: doesn’t last as long as teak. Not as soft under barefoot. Toxic when machining large amounts.

Douglas fir is lightweight. Here, it has been mixed with utile on the tiller of this BayRaider Expedition to give it added strength and to accommodate the curve over the head of the outboard engine. Credit: David Harding

- Pros: strong, curved pieces available to avoid short grain.

- Cons: goes black when uncoated. Not very rot resistant. Reacts to fastenings.

- Pros: strong timber. Laminates and steams well.

- Cons: short grain for curved areas

- Pros: strong. Grown pieces so good for curves.

- Cons: costly. Avoid green wood.

- Pros: lightweight timber. Laminates and steams well.

- Cons: Goes black when uncoated. Not very rot resistant.

Enjoyed reading Boat wood: a complete guide for yacht owners?

A subscription to Practical Boat Owner magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

PBO is packed with information to help you get the most from boat ownership – whether sail or power.

- Take your DIY skills to the next level with trusted advice on boat maintenance and repairs

- Impartial in-depth gear reviews

- Practical cruising tips for making the most of your time afloat

Follow us on Facebook , Instagram and Twitter

- $ 0.00 0 items

Build Your Own Boat!

Stitch & Glue Designs

The Flats River Skiff 12 is a light, compact and stable solo skiff to access shallow water.

- 2″ – 4″ draft

- 1 person max

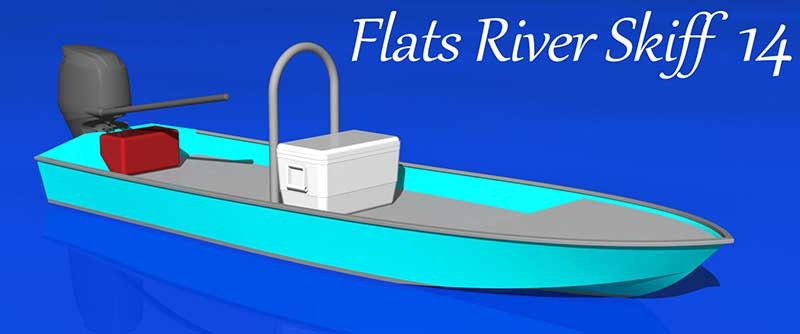

The Flats River Skiff 14 is the big sister to the FRS-12 , a light weight 2 person solo style skiff.

- 4′2″ beam

- 3″ – 6″ draft @ 825 lbs

- 2 people max

The Flats River Skiff 15 is a flats style 2 person shallow water hunting & fishing boat.

- 15′ LOA

- 5’4″ beam

- 5″ – 7″ draft

- 3 people max

The Flats River Skiff 16 hits the sweet spot for a 3-4 person shallow water fishing boat.

- 16’7″ LOA

- 6’3″ beam

- 8″ – 10″ draft

- 4 people max

The Flats River Skiff 18 is the perfect bay and flats fishing boat.

- 18’6″ LOA

- 7’3″ beam

- 8″ – 11″ draft

- 5 people max

Cold Molded Designs

The CS-18 is a smaller version of our original CS-21 for those looking for a smaller boat with lower freeboard to inshore waters.

- Cruise 25-30mph

The CS-21 was inspired by the iconic Harkers Island style work boats. This center console design features unmistakable lines, a Carolina flared bow and a modified V bottom.

- 10″ – 12″ draft

- Cruise 30mph

The CB-17 is the sister design to the FRS-16. She stands out as a custom flats boat with Carolina flare and rounded transom.

- 17′ LOA

- Cruise 25mph

The C-25 is a North Carolina sport fishing boat in a trailerable center console layout. With Carolina flared bow, broken shear and tumblehome she is an iconic design.

- 28′ LOA (25’2″ hull)

- 8′6″ beam

- 16″ – 18″ draft

- 350hp single or twin 200hp max

- Cruise 30-35mph

More Info and Helpful Links

How to videos, plans & kits.

Best Wood for Boats: Finding What Works for You

Availability, size and cost, ease of use, elemental resistance, classic appeal, easy to work, myboatplans: how to find the perfect wood, final thoughts.

To make sure that your boat lasts for many years of use, you need to make sure that you use the best wood for boats .

Every boat enthusiast has their preferences for boat building materials, but there’s no arguing that some are simply better than others.

Top resources, such as MyBoatPlans, can help you to find the right wood types for different areas of your watercraft.

Considerations to Keep in Mind

There’s more to choosing wood than settling with certain varieties that are recommended by the professionals.

You’ll first need to make sure that certain wood types are available in your area. Otherwise, you’ll be faced with several excessive shipping and handling costs.

Some types of wood might need to be imported from different states or countries, tripling your costs.

You might also find that certain woods can work just as well as your top choice and are available to be sourced locally.

It’s a great idea to make a list of your top varieties and then rank them based on how easy they are to find.

Another essential factor to consider is whether your desired wood comes in the right size.

Certain woods can only be purchased in individual widths and lengths, making them ideal for a specific placement.

For example, the wood used in your cabin might not be large enough for the ribs.

If you need wood cut to specific sizes, you can guarantee it will also increase your coat.

Often, it can be better to opt for certain types of wood specifically meant for trim, flooring, ribbing, and more.

Once you get more experience with boat building, you can be a little more flexible with the wood you choose.

Some materials might be more challenging to work with than others in terms of holding nails, bending, or strength.

You might even find that you’ll need special equipment for certain varieties than others, which can be challenging to find for beginners.

Best Woods for Boat Building

There are more than enough wood options out there that are perfect for boat building. Among the most used are the following:

This wood is one of the easiest to source in North America, especially in the United States.

Another advantage of cedar is that there are several different kinds to consider, which are all easy to work with.

You can find them in longer lengths, with knots, or in grain-free designs. You can even find different cedar types with predrilled holes so that you won’t have to worry about splitting.

Because fracturing is one of the main disadvantages to cedar, it’s something to take into consideration.

Western Red Cedar

This cedar type has lesser tensile strength than the other types, which means it’s excellent for bending.

You wouldn’t typically consider using it for planking, but it can be phenomenal for small boats combined with fiberglass.

Another benefit is that western red cedar is often used for decking, so you can easily find it in your local hardware store.

Alaskan Yellow Cedar

There’s no doubt that Alaskan yellow cedar is one of the hardest types of cedar.

It gets its name from its distinctive yellow color, and fortunately, it is also available at long lengths.

White Cedar

Northern and southern white cedar are harvested from the south and southeastern parts of Canada.

Both the northern and southern varieties are very aromatic and are relatively rot-resistant.

They’re also close-grained and relatively easy to work, which makes them convenient for beginners.

Port Orford Cedar

Port Orford cedar is one of the more popular materials for planking, but it’s also used for interior finishes.

It’s easy to work, and you can find it in longer lengths than the other types of cedar on this list.

If you’re in the market for a wood type that will take quite a beating from tools , ash is one of the best to choose.

This material works well with sanding and sharp tools. Not to mention, it bends easily when exposed to steam.

Unfortunately, it’s not rot-resistant, so it’s not your best option for planking. Instead, it is great for frames, handles, poles, boat hooks, and more.

You can typically get your hands on cypress for the lowest cost if you live near the Gulf coast of the United States.

Cypress is a phenomenal wood for planking because its natural resin is fully resistant to dry rot.

Because these trees grow in the swamps along the Gulf, you can guarantee optimal water resilience.

Cypress is relatively lightweight with moderate strength, but it does tend to absorb a lot of water.

When your boat is submerged, it will be much more massive, so you won’t want to consider it for land transport.

For example, if you’re building a portage craft, cypress is one of the top materials to avoid using.

When deciding on elm for your boat, you will undoubtedly want to focus primarily on rock elm.

It’s one of the most prestigious woods due to its heaviness, strength, and resilience, which also makes it difficult to source.

Even if you live in the Northcentral United States, where it’s familiar, rock elm is challenging to get your hands on.

Still, no one can deny that rock elm is a phenomenal choice for boats because it offers optimal shock resistance, making it ideal for all water conditions.

You’ll also find that it creates an incredibly sturdy frame for the bottom of boats, while in England, they use it for planking.

If you can find rock elm for a reasonable price, it is surely one of the better types of wood to consider buying.

Out of all the other types of wood on this list, oak is the most prevalent in shipbuilding.

Because it is quite affordable and easy to source, it has become the go-to material for beginners and veterans.

Similar to cedar, there are a couple of different types of oak to consider.

Compared to red, white oak is far more popular because it’s relatively easy to work with and offers plenty of strength.

Many shipbuilders use it for longitudinal timbering because it doesn’t shrink or swell when it gets wet.

Also, it’s known to hold fastenings particularly well, so you won’t have to worry about taking extra steps for durability.

Regardless of how you purchase white oak, it is highly resistant to dry rot, making it easy to store.

There are a few similar traits between white and red oak, primarily its ability to bend with steam.

However, it’s the less popular of the two because it’s much softer and is more likely to absorb water.

You’ll have to make sure you pay special attention to painting and finishing the wood to protect it from water.

If you’re searching for a type of wood with strong roots in history, teak is your best option . It’s typically used for boat building in the East Indies and Burma.

The natural resin in its fibers is what makes it resistant to water soakage and dry rot.

The unique aspect of teak is that it can sit unfinished for years and never fall victim to elemental damage.

Most of the boats built with teak can last centuries, especially with expert craftsmanship. However, this also means that it’s one of the most expensive materials to get your hands on.

You’ll frequently find that teak is used on luxury cruisers, especially multi-million dollar yachts.

In North America, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to source enough teak to build an entire boat. Although, you can find smaller pieces for elegant finishes, such as rail caps and trims.

It’s not beginner-friendly due to its cost, and there is a minimal margin for error when working with such an expensive material.

Best Wood for Boats: Mahogany

One thing that most boat builders can agree on is that mahogany is the most available timber to have on-hand.

It is the type of wood that can have anything thrown at it, and it will handle it with ease.

Many things make mahogany your best option, apart from oak.

Mahogany has gained a reputation for being high-quality in several ways, especially as it’s made from heartwood.

With a natural resistance to rot and decay, as well as a phenomenal denseness, it’s ideal for preventing shrinkage.

It is frequently used with boating, but it is also a widespread material source for house building because of its resilience.

You’ll finally be able to use a timber that maintains your boat’s structure but also looks great over time.

Even though your boat’s framework is the most important, you’ll also want it to look professionally finished.

Mahogany has a classic and timeless appeal that is sure to suit the needs of any boater. It feels and looks luxurious, whether used for framing or finishing.

Another advantage of mahogany is that it’s easy to finish with varnishes, stains, and paints. You can easily customize the look of the wood to meet your every dream.

It’s easy for certain types of wood to look great and have elemental resistance, but are they easy to work?

Mahogany packs a powerful punch in machinery and hand tools, allowing you to work it with ease.

Even beginners won’t find it too difficult to use, so it can easily be specified to meet your requirements.

To get the most benefits from this wood, you’ll want to make sure you source it from a reputable retailer.

Ideally, choose someone who sources their wood sustainably to ensure quality and environmental protection.

It’s easy enough to listen to the advice of others when you’re looking for timber. However, you must remember you’ll need to find the perfect choice for you.

MyBoatPlans can help you to source the perfect type of wood for every part of your boat.

By taking the guesswork out of planning, you can use this comprehensive guide to make the most of your time.

You will learn about the dozens of wood species and why they’re recommended for specific applications.

You can also use the more than 518 step-by-step plans to decide which type of wood you’ll use for specific areas.

MyBoatPlans is not only an excellent resource for boat building but also all of your finishing touches.

With the help of the crystal-clear photos to guide you through the building steps, you can get inspiration for finishing touches.

All boating enthusiasts will find it much easier to create a custom aesthetic that is sure to turn heads with the help of MyBoatPlans.

When searching for the best wood for boats, it’s important to remember there’s plenty to choose from.

Some varieties might be better for the environment, while others could be more affordable due to their availability.

With expertly written guides, such as those from MyBoatPlans, you can easily find the perfect timber for every part of your boat.

4 thoughts on “Best Wood for Boats: Finding What Works for You”

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your article seem to be running off the screen in Ie. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the issue solved soon. Kudos

Hello and welcome! Thank you for letting us know. We’re looking into it 🙂

This is the perfect web site for anyone who really wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually will need to…HaHa). You definitely put a fresh spin on a subject that has been discussed for ages. Excellent stuff, just wonderful!

Thank you so much for your kind words. We really appreciate it when you guys leave us comments…motivates us in sharing more high quality content 🙂

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Get your Boat Building Free Guide

Six Ways to Build a Wooden Boat

A guide to common construction methods

From Issue Small Boats Annual 2015

Popular Small Boat Construction Methods

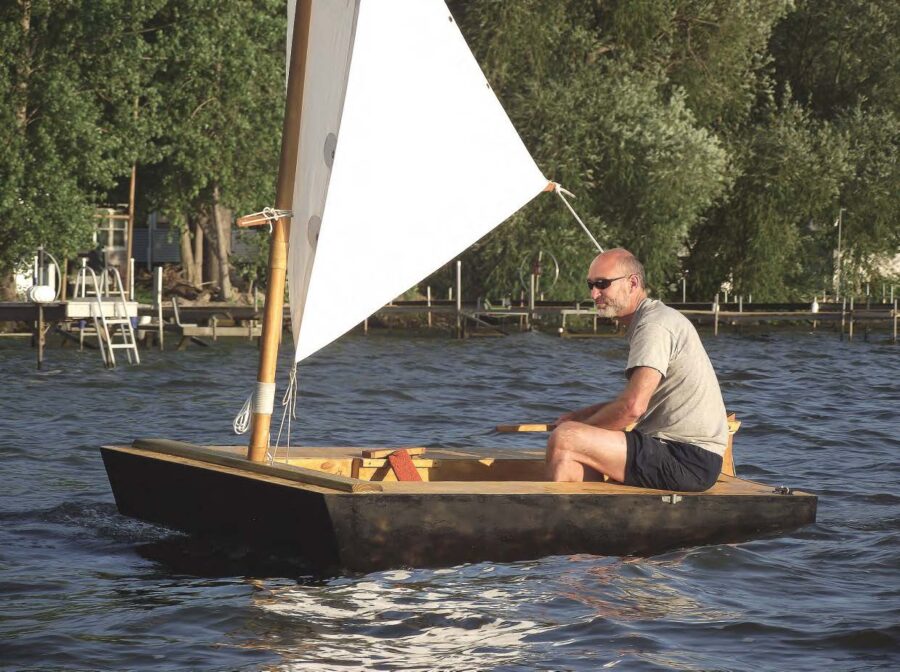

S mall boats are not small undertakings, not if we are contemplating their creation in our own garages from piles of wood. If we’re amateur builders, particularly first-timers, the prospect is daunting, maybe even frightening. We don’t know how to do this. We don’t know if we can do it. We’re about to commit epic blocks of time, money, and emotional capital to a project with no guarantees, except that—trust this formula!—it will cost twice the estimated budget and four times the projected hours to complete it. But if we stick it out, we will have not only refined our problem solving and tool skills, but also burnished our character. And we will have a boat to be proud of.

One way to gain an understanding of various methods of construction is to take a class. At WoodenBoat School in Brooklin, Maine, for example, students in a two-week Fundamentals of Boatbuilding class learn several styles of traditional hull construction. In the foreground, a students fits a floor timber to a carvel-built boat, while in the background students fit a lapstrake plank.

The question of how to build this boat is a basic one that has to be parsed at the outset, while we’re sorting through designs and deciding which to build. There are about six ways of building wooden boats today, with variations on each. Our choices have proliferated just since 1950, thanks to the innovations of plywood, epoxy, and synthetic fabrics. No particular method can be proclaimed the best; each comes with its own suite of advantages and drawbacks. The type of boat and its intended use figure in. Even more does the level of skill and mindset of the prospective builder. A powerful determinant of whether we’ll end up with a real boat is perseverance, which is most sustainable when we find joy in the work. Some people will love the painstaking process of carvel planking, inserting themselves into a continuum of craft that has hardly changed in 500 years. Others will find this ancient discipline ludicrous, and will really groove on epoxy’s magic. For obvious reasons, it’s wise to contemplate all this before making the commitment.

There are serious passions and partisans afloat in these waters, so I expect challenges and complaints. I will try to stay objective and keep my own prejudices in the locker. I’ve built strip-planked and stitch-and-glue boats, and currently am engaged in a glued-lapstrake daysailer, so I’ve had experience with three of these six methods. I’ve also been hanging out at the Northwest School of Wooden Boatbuilding, observing several boats being built with other methods, and I’ve been pumping the instructors for information (see WoodenBoat magazine No. 241 ). They’ve been generous in sharing both knowledge and opinions.

If you are a serial boatbuilder, you’ll find that your craftsmanship and problem-solving skills rapidly improve from one boat to the next. This is particularly true if you stick with one method. It’s like visiting France again and again—you feel more secure navigating; you begin to understand the nuances of the culture. But there’s also a powerful argument for exploring the new and unfamiliar. As the Zen teacher Shunryu Suzuki proclaimed: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few.” Who’d have predicted, back in the 1950s when the future of pleasure boats appeared to be a sea of white plastic, that the 21st century would offer so many new ways to begin a wooden boat?

Here are the six common ways to build a wooden boat:

Carvel-planked small boats are typically built upside-down over a building jig. First, the backbone is installed and frames bent into place, then the planking starts. At right, students use a “spiling batten” to determine the necessary curvature of the next plank.

1. Carvel Planking

This, one of the classic methods of wooden boat construction, is what made Columbus and Magellan possible. Since a carvel-planked boat derives most of its structural strength from its frames—the rib cage, in effect—its size is not limited by the length of the available timber. A shiplength strake can be made from several shorter, butt-joined planks. Hence the astonishing 262′ WILLIAM D. LAWRENCE, a carvel-planked square-rigger launched in Nova Scotia in 1874. The largest wooden ship ever built in the United States, just short of 330′ on deck, was the six-masted schooner WYOMING, launched at Bath, Maine, in 1909.

But for our purposes here, we’re talking about small boats. Until the mid-20th century, many rowboats and sailing dinghies of 10′ to 20′ long were also built with carvel planking. They were probably better suited to that time than today, because boat owners tended to leave their small boats in the water all season, which allowed the planks to swell with water, closing up the seams. A carvel-planked boat left in the driveway on the trailer will dry out in the summer sun; as the wood dried, the planks shrink, allowing its seams to open, and only a few days in the water will close them up again. That’s not an ideal scenario for impulsive trailer-sailing.

Carvel planking requires close fits; here, a student working on the final plank, called the “shutter,” uses inside calipers to determine the exact width at a frame.

But carvel planking still has its adamant and loyal partisans. Jeff Hammond, who has taught traditional for 30 years, believes it’s still the best medium to teach craftsmanship. “It’s complicated,” he says. “Every step requires you to stop and think about what comes next. A lot of care has to go into each piece.”

And here’s the clincher, for Hammond: “It’s a relatively pleasant experience, as opposed to covering yourself in goop all day long.”

But the word “complicated” remains embedded in any discussion of carvel planking. It’s hard to describe the whole process in a digestible paragraph, but at terrible risk of oversimplifying, here goes: Set up a regiment of molds (cross-sections of the hull form at regular intervals, typically one foot apart) over which the boat will be built upside-down. Connect them with temporary stringers called ribbands. Steam or laminate the frames, which are the structural ribs, to precisely fit outside the ribbands. Sculpt the planking around the frames to form the skin of the hull, precisely beveling each plank edge to mate with its neighbor, leaving a slight gap on the outside as a caulking bevel. Screw or rivet the planks to the frames, bung the fastening holes, caulk the seams, and assiduously fair the outside surfaces to eliminate any unevenness.

Planks fit tightly together on the side of the hull but are given a deliberate bevel—a “caulking bevel”—so the seams can be caulked with cotton, followed by primer paint and then seam compound.

The most difficult part of the operation is likely to be the rolling bevels on the planks. The builder will cultivate the patience for many trial fittings and excursions back to the workbench—with each one of the 16 or 20 planks typical on a small boat. Sometimes planks have to be steam-bent. Sometimes they crack during the final fitting and you start all over. If one is meticulous about fitting and caulking, however, the leakiness that plagues some carvel-planked boats may be spectacularly absent: They can be built so tightly that they don’t ship a drop.

Pros and Cons to Carvel Planking

- Teaches the builder to cultivate excellent craftsmanship

- Many classic designs available

- Damaged planks can be replaced with relative ease

- Heaviest method of construction

- Complex and difficult to master

- Happiest living in the water, not on a trailer or in seasonal storage

- Suitable materials may be difficult to find

Lapstrake construction sometimes involves building right-side up— and in the case of traditional Scandinavian practices, without any cross-sectional molds. Few frames are required, and along with floor timbers and other interior structure, they are fitted as the planking proceeds or after it is all finished.

2. Traditional Lapstrake

Lapstrake planking is cool for several reasons, but the most obvious is aesthetic: Small boats constructed of shapely overlapping planks are inherently attractive. The parallel flow of sweeping lines with their tiny shadows creates a rhythmic vitality and makes the hull form seem more like an organic creation. We are naturally attracted to repetition in lines and forms; it’s an aesthetic principle that seems rooted as deeply in boatbuilding as it is in art, architecture, music, and even the written word. Perhaps it makes complex things more understandable by breaking them into their component forms.

How complex are lapstrake boats? Lining off the individual planks, warns boatbuilding author Greg Rössel, is “more art than science.” Individual planks, off the boat and on the workbench, may assume unbelievable, bizarre shapes—some will be fingernail-clip crescents, others vague, squashed-snake S-curves. If these planks aren’t lined off with care and precision, the boat will take on a misshapen, bloated appearance. It will, however, still function as a boat: lapstrake forgives small imperfections more graciously than carvel. Some designers have begun making full-sized Mylar patterns available for cutting the planks, which greatly enhances the amateur builder’s chances for accuracy. After the planks are shaped, they must also be beveled or rabbeted on their edges so they mate tightly with their neighbors, and beveled again at the forward ends so the strakes become almost a flat, carvel-like surface as they flow into the stem. These can perplex like the very Devil’s bevels.