How to Tune a Sailboat Mast

Here are some general guidelines for tuning your mast’s standing rigging . please see our blog on how to properly adjust a turnbuckle before you begin. as always we recommend seeking the advice of a professional rigger for more specific tips and tricks regarding tuning your boat’s rigging..

Your boat must be in the water. Begin by just slacking off all of the side shrouds as evenly as possible, so that all stays can be adjusted by hand. Once loose, try and adjust all turnbuckles so that they are pretty much equally open (or closed) from port to starboard respectfully. Also go ahead and line up the cotter pin holes (if present) in the studs so that they are in a pin-able position. Now is also the time to balance out the threads, between the upper and lower studs of the turnbuckle, IF they are not even. Do this by unpinning the turnbuckle from the chainplate – BE CAREFUL HERE – to ensure the mast is secure before unpinning any one stay. Lastly, loosen all halyards or anything that may pull the mast to port, starboard, forward or aft.

1. Check by sighting up the backside of the mast to see how straight your spar is side to side. You can take a masthead halyard from side to side to ensure that the masthead is on center. Do this by placing a wrap of tape 3′ up from the upper chainplate pin hole on each upper shroud. Cleat the halyard and pull it to the tape mark on one side, mark the halyard where it intersects the tape on the shroud. Now do this to the other side, the mark on the halyard should also intersect the tape similarly. Please note: when the mast is equipped with port and starboard sheaves, instead of just one center-line sheave, it will appear slightly off to one side. Just keep this in mind……

2. Using the upper shrouds as controls, center the masthead as much as possible using hand tension only. Some masts are just crooked. If yours is(are) crooked, it will reveal itself when you loosen all of the stays and halyards initially and sight up the mast. Although you should use hand tension only, you can use a wrench to hold the standing portion (the stay portion) of the turnbuckle. If for some reason the shroud is totally slack and you still can’t turn the turnbuckle by hand then the turnbuckle may need to be serviced, inspected, and maybe replaced.

3. Tune the mast from the top shroud on-down, making sure the mast is in column. Remember: as you tension one shroud by adjusting the turnbuckle, to loosen the opposing shroud the same amount.

4. Once the mast is fairly straight from side to side, tighten the shrouds all evenly using tools for tensioning. Typically, for proper tension, the shrouds should be tightened using these guidelines; uppers are the tightest, and then fwd. lowers, then the aft lowers and intermediates should be hand tight plus just a turn or two. ~ With an in-mast furler it is recommended to tension the aft lower a bit more to promote a straighter spar (fore and aft) for better furling.

5. Now you can tension the aft most backstay (s). If the backstay has an adjuster it should be set at a base setting (500-1000 lbs). If the backstay simply has a turnbuckle then it should be tightened well. After this has been done, in either situation (adjustable or static backstay), one should site up the mast from a-beam and notice that the masthead has a ‘slight’ aft bias. If there is no aft bias, too much, or the mast is inverted (leaning forward), then the forward most forestay (s) will most likely need to be adjusted to correct this. If a furler is present then seek the council of a professional rigger or refer to your furler’s manual for instructions on how to access the turnbuckle if there is one present.

6. Finally, sight up the mast one last time and make any necessary adjustments.

7. MAKE SURE ALL TURNBUCKLES AND PINS HAVE COTTER PINS AND ARE TAPED NEATLY TO PREVENT CHAFE!

Read HERE for how to use a LOOS & Co. Tension Gauge!

Here is a little vid from our friend Scott at Selden Masts (click the link then hints and advice for more info) on rig tune…..

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rcCALZ4x6R4&w=420&h=315]

Is your mast fractionally rigged, only has a single set of lowers or is just plain different? Be sure to leave any questions or comments below.

Similar Posts

Views from aloft.

This was a spar finish and rigging package that we put together back in the summer of 2014. Originally this mast was an Annapolis Spars design (our previous employer). I love the way these masts were built. This is exactly how the top of a Pro Furl furler “Wrapstop” system should look when the sail…

Not all T Terminals are Created Equal……

‘T’ Terminals, ‘T’ Balls, Gibb Hooks, Shroud Terminals, and Lollipop Fittings are just some of the nicknames for these special fittings. I would just like to take a minute to address the different terms associated with these fittings; their uses and misuses. It appears that many boats in today’s sailboat market use these types of…

Something of a Different Flavor

We don’t usually post about something like wake-skating as it is not really sailing related. Being that this sport gets very little publicity, I figured I’d share. I mean, it is a water sport after all and a pretty impressive one at that. [youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IKfNf1azEm0&w=560&h=315] Wake skating should win some sort of award as being the most…

I guess this time of year we go aloft a lot, because I sure have been aloft a lot. Can anyone tell me what shore this is? We have certainly been to this place before but not down at this end. How about, which marina is this? This was one of our standard FREE inspections….

The Clipper Around the World Race is my latest discovery (although I am sure most of you already know of this). This is essentially a Volvo Ocean Race for amateurs of all shapes and sizes. It seems the boats are all one design and fully rigged and equipped to handle the challenges of the open…

The 2nd Annual Spring Boat Show…

…Starts today in beautiful downtown Annapolis’ City Dock.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

61 Comments

Hi, I have a masthead 3 swept spreader adjustable backstay Evelyn 25 and I have been trying to find information on rigg tuning for this boat with no luck. Closest thing I come up with is a J24. Can you shed any light or point the way on tuning this great boat?

Thanks for the read and for reading the comment section first. Evelyn’s were great boats, still are if maintained. You say you have 3 spreaders?? That would be unusual for that LOA. From What I recall about the Evelyn is the spreaders are not swept aft at all, but straight out. Correct me if I am wrong and if different send us some pics to [email protected] to discuss further.

One thought is have you played with headstay length? So with back stay adjuster all the way off, the headstay should be very slack and the mast should be very straight up and down when looking at the boat from a-beam. If not, adjust the headstay and the backstay length to achieve a straight mast with almost NO rake.

The other tips are, as you’ve read, ensure the static tune is correct, e.g. masthead centered and the rest of the rig is in column. As for tension, since it is a race boat, start with the lowers and the intermediates pretty soft. Next go sailing close hauled and adjust leeward shrouds as needed to {just} remove slack, count the turns, tack and add the same amount of turns on the other side. The shrouds should go slack in the puffs, and in the really light stuff set the rig as light as you are comfortable with…then maybe take another turn off ;-0). You can purchase a Loose tension gauge to THEN start recording the various tensions at various wind/ wave conditions, make a chart for ease of future duplication.

The next step, if you can, gauge yourself off of another Evelyn25, beating and running, that would be ideal. If not other Evelyn 25’s are available, pick a similar design to match. Then see if your lower/slower, going upwind, or higher/slower, going down wind. If you can narrow things down to being a specific problem it will help you begin to identify the fix; which could be rig tune, sail/ boat trim, the sail themselves, or any combination thereof. Fix the rig tune 1st, then the sail and boat trim, then once you are feeling pretty good about that…..get some new sails!!!

….all of this taking into account that the hull and it’s foils are clean and fair.

Win the start, then extend your lead.

Great article to start with, I too am looking for some tips to tune my Evelyn 25. The 1rst year I rigged and tuned the mast the boat seemed very fast, (of course I didn’t write anything down). The next year did not have the same results, in fact it was terrible. Apparently I didn’t remember what I did the 1rst time. I’ve read through a bunch of the questions trying to glean tidbits from here and there, but need a little help. I have a 3 swept back spreader mast, with adjustable backstay . Any insight would be greatly appreciated

I have a fractional rig with a cap shroud and one lower V1. The spreaders are swept aft with no backstay, and the rig is set up for a fathead main. The worse diameter is 5mm. The boat is 23 feet long. Could you provide any tuning advice for this style of rig. The past owner said he set the rig up at 10% breaking strength on the upper and 4% on the lowers which seemed really low for this style of rig. Any input would be very helpful as we go to rig the boat tomorrow

If you look at our reply below for the FarEast 23R tuning explanation, this should help shine some light on the topic. As far as percentage of breaking strength is concerned, just ensure a good static (dock) tune, then sail-tune setting tensions to the minimum requirement, and don’t exceed 30% of breaking strength.

Cheers, ~T.R.C.

Any hints with tuning a sportboat that only has a set of uppers, a short forestay and no backstay????

Just got an email from someone else with almost the same question, for a FarEast 23r. Since I don’t know what Sport boat you have, I’ll just copy and paste my reply here. Generally, these “guidelines” work for just about ANY type of sailboat. The article is trying to focus on the concept of mast tuning rather than specific numbers, but also touch on how a guide can be created that is specific to YOUR boat and your style of sailing.

Thanks for the comment and enjoy the read.

“The Fareast 23r looks like a fun boat and simple in terms of rigging. I am a bit surprised that there isn’t any real support offered to the aft end of the top of the mast given the masthead kite. The boat must sail at enough of an angle downwind when loaded that the main leech and vang support the masthead….. but it must work.

As for appropriate tension, in terms of what’s fast, you will need to dig into the class a bit and figure out who’s figured out what. Ultimately the maker of your sails should have some data in terms of prebend for the mainsail and perhaps even jib luff curve (a.k.a. intended sag). If you can gather that info, I would do a static dock tune and then make adjustments until I achieve the sailmakers recommended pre-bend.

Additionally, you may be able to start with the Fareast 28r’s base setting for just V1 and D1 and try that to get started. Or at least see how that compares to the previous owners’ notes.

I haven’t’ sailed the boat but as a general guideline, and as you will read in the comment section of this article, you will need to start with good dock tune. The amount of tension is irrelevant at this point, contentedness and straightness is numero uno….. and then just the order of tension.

Order of Tension (Single aft swept spreader rig) – the uppers are the tighter of the two: upper and lower. The upper is in charge of providing you headstay sag (or tension). The lower will allow the mast to create mid mast bend, or keep it from bending. The forestay length gets adjusted to affect the mast’s rake, the amount aft lean.

Once a straight and centered mast with adequate rake and a touch of pre-bend is achieved (static tune), using hand tension only and you can’t tighten it ‘by hand’ any further, add three or four whole turns to the uppers and one full turn to the lower. If you have pre-bend recommendations, now check them and adjust as needed. Then go sailing close hauled, ensure you are trimmed and canvased correctly given the condition, and observe the leeward shrouds.

IF the leeward shrouds are flailing about loosely in the lulls, add tension by hand while sailing until they just begin to fetch up. Count the number of turns, tack and do the same thing on the other side.

IF the leeward shrouds aren’t slightly moving in the lulls, you’re likely a bit a tight and you should do the opposite of the above procedure.

For me, while sailing close hauled, properly trimmed, and properly canvased, if I see the leeward shrouds just starting to slack in the puffs or waves, then I feel like the boat’s tune is typically pretty dialed in. Then if I want to make cheat sheet “Tuning Guide” when I get back to the dock, I pull out my loose gauge, pen and paper and note: today’s wind and wave condition, and the Loos Gauge setting that I thought was ideal.

Soon you’ll have created the Fareast 23r Tuning Guide😉

Hope that helps.”

I have a 1965 Alberg 30. On a starboard tack the boat has more weather helm than on a port tack. I have not been able to achieve a balanced helm on either tack. New full batten main, new 150 roller furl genoa.

Other than the boat being evenly ballasted from port to starboard, e.g. holding tanks, fuel tanks, below deck furnishings, and storage items, I would check the rig from side to side. A crooked mast or poor static tune can result in the boat sailing differently on both tacks. A good way to test this is either sighting up the mast at the dock to ensure that the mast is relatively straight side to side and in column. You can also see that when beating (aka hard on the wind), you have to make adjustment’s to the mainsail sheet tension (NOTE: the traveler will likely need to be adjusted to mirror the same setting as on the previous tack). If notice that with the traveler in the same position on each respective tack that the sail is bubbling or flogging more on one tack than on the other, it is likely necessary to re-tune the mast. This can be done at the dock by following the guidelines in the article once the everything has been appropriately loosened to tension.

Let us know if this helps.

Any Hints, tips for tuning a 1977 Whitby 27 sloop 1/4 ton rig?

Nothing special that I can think of. Just follow the guidelines in the article. From what I can gather there are only a single set of lowers correct? Are the spreaders aft swept at all or just straight out? If it is single lowers and no sweep to the spreaders you’ll need to set the rake using the forestay adjustment to set the rake and the backstay to control the forestay tension. If you are interested in optimizing sail tuning, like in racing situations: higher wind sailing conditions will desire more tension on the shrouds, a bit more tension on the lower than the upper, but only slightly; and in lighter winds loosen them up a bit, a tad looser on the lower than the upper.

Hope that helps, and good luck.

How do I tune /2 in rigging. Neither of the loos gaug s are large enough?

Thanks for the question. Yes, I think the Loos gauges only go up to 3/8″ wire. First let me say that a tension gauge is not a must for proper tuning, more for tension recording and also not exceeding max tension which is typically hard to achieve without additional fulcrums or wrench extensions. Having said that, if you know that you need one simply search google for cable tensioning gauges. There are a few others like this one https://www.checkline.com/product/136-3E , pricing is not easily apparent and may be excessive for your needs.

My recommendation is that if you have a good local rigger have them do a static dock-side tune and perhaps sail-tune in the boat’s ideal conditions. Perhaps they can provide a tutorial on their process for you to be able to make rigging adjustments over time.

Hope that helps.

Hi. Nice article. I have a Mirage 27 (the Bob Perry design). It’s a masthead rig with single spreaders and the shrouds on each side come to the same chainplate. I have been tuning so that tension on the lower and uppers is the same and trying to set them so that (as you say) the leeward shrouds are just slightly slack. But how do I induce mast rake? I have a split backstay with a 6:1 purchase on the adjuster; should the mast have rake even with the adjuster off? or do I just haul on it? or should the tension on the inners and outers be different?

HI Michael,

You will need to lengthen the headstay and shorten the backstay. This can be done a few ways either with turnbuckle adjustment or actually shortening and lengthening cables, sometimes you can add or remove toggles also.

Hope that helps!

- Pingback: Buying a second-hand luxury yacht? Here’s what you need to look for - Phuketimes news

I recently purchased a 1988 Catalina S&S 38 and experienced my first launch this season, including stepping the mast and tuning the rig. As we prepared, we found that the Cap Shroud and Intermediate Shroud were clamped together at the four spreader ends. The folks at the yard had never seen that, and I certainly didn’t know why it was there … possibly to keep the spreader ends and shrouds consistent? Anyway, as I am learning how to tune my rig, it seems to me that these clamps would prevent me from tuning the cap shroud and intermediate separately and correctly Thoughts? Should I remove them and re-tune the rig?

So it is a double spreader rig I take it? The upper shroud wire should run freely through the first spreader, or the closest one to the deck, and be clamped at the top spreader. The intermediate shroud wire should be clamped at the lower spreader.

Before stepping, if this was done correctly, both upper spreader and lower spreader should be clamped equal distance from the mast attachment point, when looking at the mast from port and starboard.

In other words, you should measure the distance from where the upper shroud attaches to the mast to the end of the upper spreader and it should be the same distance on the other side, port to starboard. Then the same goes for the intermediate shroud and the lower spreader. The upper shroud should run freely through the lower spreader although it is covered by the clamp, but not actually clamped at the lower spreader, j ust the top one.

If all 4 spreaders are clamped equally port to starboard. You should be good to tune from there. The spreaders should show a slight up angle, to be specific slightly more up at the upper spreader than at the lower, but all of them should be just ever so slightly pointing up. You even want to think about clamping them slightly higher than that before tensioning, as this will pull them down and into their preferred angle, just slightly up. Specific angles are really only determined on the spar builders drawing and vary for manufacturer to manufacturer. Generally it is pretty clear where they want to sit. With the shrouds loose if you find that angle that appears to be the right one, and push them up slightly from there then clamp. This will allow them to be pulled down slightly once tensioned.

Kind of a tricky thing to explain in writing but hopefully it helps.

Have further questions? Give us a call 443-847-1004, or email us [email protected]

I have a Catalina 275 fractional rig with single swept back spreaders and an adjustable backstay. My questions are: how much rake, tension on cap and lower shrouds and on chain plate should cap shroud be forward and lower aft. I am racing and want the best performance. Thanks for any help. Bill

If the two shrouds are on the same plate, right next to each other, and the pin holes are the same diameter, and the plate is configured in a fore and aft configuration, I would choose the aft hole for the lower shroud and the forward one for the upper shroud.

In terms of specific rake, you will need to look towards the maker of your sails and or the boat manufacturer. I discuss how to measure rake in the preceding comments.

“You can measure rake by hanging a small mushroom anchor from the main halyard, with the boat floating on its lines, if you wish”

For racing I would start off with a good static tune at the dock by following the points in the article. If you know it’s going to be light day, start off with light rig tension. Be sure to use either Velcro wrap style cotter pins or simply lash the upper and lower shroud turnbuckles together to secure them. This will give you access to removing the pins or lashing while sailing and adjusting the stays.

From there you will need to sail tune for that days specific conditions, your shrouds will tell you what needs to be tighter and looser. I have answered how to do this a few times already in the comments below, please take your time to peruse the comments section to see what sail tuning entails. Doing this will always ensure that the cable tensions are set up ideally for the conditions and the boat can be sailed at maximum potential.

“For racing, ideally once the static tune at the dock (the part we just talked about) is done, go out and sail tune. Do this by going hard on the wind and checking to see if the leeward shrouds are just starting to dance, this is ideal. If they are swaying about they are too loose for the current conditions. If the leeward shrouds are tight, they may be a touch to tight. Tension and loosen as needed; count what you did and to what shroud, then tack and do the same to the other side.

ALWAYS secure the turnbuckles when you are finished adjusting them.”

Just hit ‘Ctrl F’ and search the page for “sail tune” and “rake”

I am trying to tune a Hallberg Rassy HR36 masthead rig. The rig has two in-line spreaders. The cap shroud is 3/8 inch and terminates at the lower spreader. From the lower spreader, the cable transitions to a 5/16 inch cable passing over the upper spreader to the masthead. A second 9/32 inch cable runs from the lower spreader to the mast (just below the upper spreader). The Selden rigging suggests that the “upper shroud” be at 15 percent of the breaking strength of the cable. In this situation, is it 15 percent of the 3/8 inch lower portion? If so, how should the upper 5/16 inch and 9/32 inch cables be tensioned?

Thanks for your help.

Hi Bryant, good question. Once proper alignment and centering of the spar has happened (static tune), and you are perhaps a hair tighter than hand tight on all shrouds, you can begin to tension things to a percentage of breaking strength. Do this by using the cables at the deck and use their diameters to determine the tensioning amount.

The V1 (aka cap shroud) in your case is a 3/8″ cable which supports the two cables above ii, hence its large diameter. The 5/16 V2,D3 and the 9/32 D2 total 19/32. So if 15% of the 3/8 cable is achieved you will below that threshold for the cables aloft. Does that make any sense?

With that in mind there is a range of acceptable tension from light air to heavy air. 15% sounds like a good middle of the road tension. Generally you do not want to exceed 30%. Sail tuning in ideal conditions is generally the best way to determine the right tension, but 15% of breaking strength sounds like a good place to start.

Don’t forget your cotter pins and tape, especially aloft.

Hope that helps and thanks for the question.

T.R.C. Thanks you for the clarification regarding the V2,D3 and D2 load distribution. When I set the V1 tension to 15%, the tension on the V2,D3 was at 8 %. I then tensioned the forward shroud to 12 % and the aft shroud to 10 %. Then I tensioned the backstay to 14 %. After doing this, I measured the tension on the V1 to be 10 %. The only information I could find regarding tension on the D2 was that is did not have to be tensioned much. I tensioned it to 5%. The mast sights straight and I used a bossen seat on a halyard to measure to the lower part of the V1, which also indicated that the mast was straight. Did I overtension the fore and aft stays? Is the tension in the D2 too much or too little? Again, I appreciate your advice.

When you tighten the backstay it usually induces a bit of aft bend in the mast which will soften the upper shroud (V1) a bit. You can just take up on it again to get it back to 15% if you like. As I said there is a acceptable range for all of the stays, which you are well within. Everything else sounds like you did a pretty good job. Next up sail tune and see if there is excessive waggling on the leeward side, but in moderate breeze. The shrouds will begin to sway as the breeze builds, this could be a telltale to either reduce sail a bit or you can add some tension to the shrouds all the way around.

Should be all good as they say.

T.R.C., your advice has been invaluable. I took her out in 12-15 knots and was very happy with the sail luff and stiffness of the rig. Thanks for you help!😁⚓️

Hi , can you provide any tuning guides for a Swan 38 Tall mast single spreader rig with baby stay, I am keen to set the rig up for new North sails and race her competitively. The mast is an exact Nautor factory replacement in 1998. She shall not have furling sails.

Hi Peter and thanks for the comment.

Unfortunately we do not have a guide for that boat. I would ask the sailmaker however to see what info he or she might have. Alternatively you can always start with a good static tune and then sail tune the boat as I describe in some of the comments below. This is the best way. I may use a Swan 45 Tuning guide as the template and then just fill in my own numbers over time. This is ideal, but infidelity start with asking the sailmaker you are working with, he should have some good info.

This may seem like a silly question, but it has me perplexed. How long should my cotter pins be? Long enough to ‘jam’ against the surrounding body, to prevent rotation? Otherwise, I don’t see how they’ll prevent my stays from loosening.

The length should be the minimum amount to just be able to bend the legs. Too long and they get caught up on things, too short and you can’t adequately bend the legs to keep the pin in place. The head of the pin is a actually providing the security.

Does that help?

Great article to get me started, thanks! I just have a few questions…

I originally owned a Tanzer 7.5. Her mast was rigid and simple to tune with a LOOS and an eyeball. I however now own a Mirage 33 (1982) and things are a bit more complex (but not too much). When I bought her the mast was already stepped and the owners said they replaced the forestay (inside the furler) 1 season ago. I went about the boat tuning the rig as best I could but I started second guessing the rake. I found noticeable rake in the mast with virtually no backstay tension on. So I think my forestay stretched (being “new”) and I need to bring it forward.

How do I measure how much rake (at rest on the tensioner) is enough? With my rig as is I felt worried that if I pulled down on the backstay tensioner I might buckle my mast by bending it too far. It seems to me it’s ALOT of downward pressure on the column when you pull down on her especially if the mast was already raked or maybe in my case leaned too far back to start? She has a babystay too, I wasn’t sure how far to tension that other than to assist adding bend\rake but since I had too much already I just lightly tightened it and hoped for the best!

Thanks for the question. With the backstay tensioner completely off, you should be able to adjust the static/ base tension of the backstay with a turnbuckle (s). Loosen the Baby Stay so that it is completely loose, sloppy, to take it out of the equation. Then mark furling line spool direction and remove the line. Next, open the furler up to gain access to the turnbuckle inside, if present. Remove all cotter pins or locking nuts to free the turnbuckles on the headstay and the backstay. You should then loosen things so that the headstay and the backstay can be adjusted by hand. Close the headstay turnbuckle and open the backstay turnbuckle to reduce rake, and vice versa if wanting to add rake.

You can measure rake by hanging a small mushroom anchor from the main halyard, with the boat floating on its lines, if you wish. Then once you achieve the desired mast rake go ahead and tension the forestay and backstay a few turns equally with tools; not too tight, but a good base light air setting, or as loose as you can imagine the headstay ever needing to be. Lastly, tension the baby stay a bit until it just starts to tug on the mast, helping induce bend. From here the backstay tensioner will do the rest: wind it on and it will tension the headstay and induce mast bend via the baby stay. You may have to take the boat sailing and adjust things as you find out how it performs at various degrees of rake and bend.

I hope that’s not too wordy, but helps explain it all a bit. Feel free to email or call with further questions.

Regards, ~T.R.C.

Can you provide some specific information regarding rig for 1980 C&C 32. Looking to purchase new main and want to get the most from it for Wednesday nights. Boat currently does not have a pony stay, it has been removed. Can replace that track/car. What should initial bend look like, keel step is fixed so assume I need to some chock aft of mast at deck? Have rod rigging but no Loos gauge for same, should I acquire one? Love this site, very helpful RayK

Thanks for the compliment. This may be less technical than you might expect. I would start with the basic guidelines given in the article to ensure a good base, static tune setting. A Loos gauge is good but not needed. If you focus on getting the spar straight, side to side, with a slight aft bias and then the tension is set so that it feels fairly tight. I know that sounds vague, but keep this in mind: if you are anticipating heavier wind make things a bit tighter, and loosen things up if less windy. The order of tension, in regards to the which shroud (upper vs intermediate vs lower) is important; more so than the amount of tension. Make sure nothing is so loose it is just flapping about.

The headstay should have some good slack to it with the backstay adjuster totally off. Adjust the backstay and headstay turnbuckles, with them in the slack position until the masthead is favoring a slight aft lean or rake, but only slight. From there, tension the backstay adjuster very tight and see what the headstay tension feels like, should be very tight.

PLEASE NOTE: if the backstay adjustment is totally bottomed out at this point, the backstay needs to be shortened a bit. Just pay attention to how this affects the rake. …

This part is where the pony stay or the baby stay will play a critical part, for mast bend. You may even find the pony stay to be good for mast pumping in light air and waves. Making this baby stay removable is a good idea, as well as, we’ve found that Dynema rope is the best choice here.

So… a centered mast head, side to side. A straight, in column mast from the top on down. A slight aft rake to start with…and as you begin to wind on the backstay and the baby stay you will add some rake but also a good bit more bend.

Take this set up for a few test sails and see how things act, in different conditions. After that you can make some adjustments here and there as needed: weather helm, shroud tension, mast rake, pre bend, etc…Moving chocks and using a Loos gauge.

ADDT’L TIP: Chocks and mast step position affect bend and rake properties. Want more rake? Chock mast aft in collar and move step forward. Want more bend? Chock mast forward in collar and move mast aft. As all things, there is more to it than that, but that’s the gist of the whole chocks and mast step thing…

“Sail Tuning” is a blog we are in the works of, but the punchline is that if hard on the breeze, and the leeward shrouds are excessively loose, and you are sure you aren’t over canvased…then go ahead and take turns on the leeward side until they just stop waggling, count what you’ve done, tack and mirror the turns on the other side.

Once the boat is set up for that specific condition, and you return to the dock, you should take your loose gauge and record these settings…creating a tension gauge setting for various conditions.

Hi, Thanks for your information. I have a Dehler 34. 1986… How much mast prebend and rake is recommended? The boat is new to me in March. Raced ok but I want to get a new main and want it to fit a well tuned mast. What do you think of a 2 degree rake and 4″ prebend at the speaders? Also, I have a Harken furler, How do you measure the forestay tension? Thanks, Duke

The answer, this boat is pretty sporty so it should show some rake. The spreaders are swept slightly aft so this will produce some natural bend just to tension the headstay.

Head-stays are always tough to measure with any sort of gauge, there are some class specific tricks for using a gauge in funky ways in order to get data, but they aren’t really reliable in my opinion. If you live in a typically windy area, go for bit more shroud tension, headstay tension and mast bend, and see how the boat feels. This will take some trial and error. If the forestay feels too stiff, slot too tight, loosen the uppers a bit, thus reducing bend and slackening the headstay.

Once the boat is sailing well in the ideal conditions, record that bend and those tensions. This is where I would leave things set, record it, and then just adjust shroud tension to affect bend and headstay in order to compliment different wind strengths and sea states. It takes quite a bit of back and forth, and documentation to get it right. One designers have already worked all of this out and then they share it for others…..very helpful. The rest of us will have to be the trailblazers for this type of information for other boat owners with the same (similar) boats to benefit.

Hope that helps, thanks for the kind words, and good luck. Once you figure things out post a link here for others with the same boat…..would be helpful.

Hello, Thanks for all of this great info. I just purchased a 37′ boat with a 3/4 fractional rig and a tapered mast. I was wondering if there were any special considerations when tuning the fractional rig? Currently the stays and shrouds are a little loose and can be wiggled (borderline flopping) by hand although the mast stands and is visually centered. (We are in SW Florida and the boat went through a direct hit by hurricane Irma like this and still stands tall!) Also is it advisable to increase shroud tension in small increments first on one side and then do the same on the opposing side? Thanks so much for any info

Hi Nathan. There are some thoughts, so fractional masts are usually fitted with aft swept shrouds and spreaders. If so, this means that the uppers also tension the headstay and create mast bend. The lowers then also act to reduce mast bend, so the tighter you make them you are actually reducing mast curve, thus powering the mainsail up. So be conscious of these two thoughts when tensioning the shrouds. The rest is fundamentally the same as the guide suggests. Loose or wiggling shrouds (excluding the scenario where we are talking about the leeward shrouds under sail), should be tightened. Doing things in increments is definitely a good idea.

Hope that helps. Thanks for the questions.

Thanks!! Now that you say that about the swept spreaders helping create mast bend it makes perfect sense. I had an ‘oh duh’ moment. I’ll probably err on the side of looser lower shrouds knowing if we need more power we can always tighten them up. Thank you again this helped immensely!

I want to buy a tension gage. Most familiar with Loos. But do I need Pt 1 or 2? (Pretty sure I don’t need 3 or Pro.) I have two rigs to tune: a 1972 Morgan 27 and a Catalina 22, I think 73 or thereabouts. The Morgan 27 is mine, fresh water for life, and 99.9% most likely factory wire. The Catalina 22 is a borrower in the Gulf, but pretty sure the owner has never tuned it. My problem is I can’t find the gage of wire for either standing rigging anywhere! Any help?

I think this one will do… https://sep.yimg.com/ca/I/yhst-70220623433298_2270_120385950 . The Morgan is likely 3/16″ wire and the Catalina is likely 5/32″, that’s an educated guess. Hope that helps.

I just purchased a 1980 C&C 40. I was told that I need to replace the rod rigging as it is “too old”. The mast is down and the rod rigging seems ok but I have not done any penetration testing. Does rod rigging need to be replaced due to age? Thanks Rigging Co.

Not replaced, but re-headed. This can mean that some stays need to be replaced as a whole, but not typically not the whole set. There are instances where you’ve almost replaced all of it anyways, so full replacement just makes sense. Other than those scenarios, full replacement is due after a certain mileage with rod…60,000 NM. Please keep in mind these standards are very general recommendations. It sounds like in your case, you should send in the rod, tangs, and chainplates for service and inspection. once we receive everything we will make a quote for the recommended services and/or replacement.

Hope that helps and give us an email for more info.

I have had a problem with securing the spreaders to the shrouds, resulting in the spreaders dropping. I am using stainless wire to seize them but still having a problem. Any tips on how to do this properly?

Seizing the wire onto spreaders with hinged spreaders is a bit of a trick of the trade that requires some practice. We use the X’s and O’s method. The end result should be something that looks like this… https://theriggingcompany.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/2012-06-07_14-26-09_899.jpg?w=900 . A trick to make the wire bite into the spreader end a bit more is to wedge a small piece of leather between the spreader and the wire before seizing. Also parceling and serving the wire where it intersects the spreader will help create more bite too. Lastly, and I don’t like this method but you can install a bull dog cable clamp beneath the spreader, nuts facing in, to keep it from dropping when slack.

I hope that helps a little. Thanks for commenting.

I am struggling to get enough rake into my mast. 33 foot Charger 33 keel stepped. Have loosened forestay and moved mast foot forward by about 10 mm. Should the chocks in the collar be adjusted? Runners and 2 spreaders, and check spreader. Spreaders do not have much aft angle. Move mast step more forward? Outers are tight with inners looser. Thoughts?

Hey Bernard,

Yeah, it sounds like chocks are the last thing. Maybe remove the chocks with the rigging slack and see if you can get the mast to sit where you like it with just hand tension. Then chock it where it wants to sit. It sounds like you are on the right track everywhere else, perhaps add a toggle into the headstay and shorten the backstay is next. Good luck and I hope that helps somewhat.

Hi, We have a Lagoon Catamaran with fractional rig, upper and lower shrouds, fore stay and upper and lower diamonds. No back stay. The mast has a degree of pre-bend. I do not plan to drop the mast.

I may have to do some work on the port side upper diamond. Is it as easy as just undoing the turnbuckle? Or do I need to loosen the starboard one at the same time. If it needs replacement should I also replace the starboard one even if in good condition?

As a further question, what happens if a diamond breaks, does it result in mast failure?

You would need to loosen the other counterpart to that stay for sure. It is just good practice, will keep the mast straight, and also make your life easier for removal install. Now, do you replace both? I don’t know. How old is the standing rigging? Why are you replacing the one? If it is not all due for replacement and you are just replacing due to damage, just do the one, but loosen both sides to do this.

Hope that helps and thanks for the visit.

Hello! I recently purchased a keel-stepped 1982 Goman Express 30 which came with an Alado Furler. I have been sailing it since May of this year. My question is this: Despite relocating mast wedges at the cabin roof to bias the lower mast aft about 2″, I still have a pronounced backward bend (10 degrees or so) just above the highest spreader. When sailing on jib alone, most wave action causes the mast to pump right at the bend point. I have a split backstay that is as un-tensioned as possible and the forestay only has another inch of adjustment left. There is no baby stay.

How can I get the bend out of the mast? How concerned should I be that the mast might break at that point?

Thanks in advance for your reply!

Eric Hassam – Delta Flyer

Thanks for taking the time to comment on our site. It sounds like you are on the right track. So one other adjustment that you have is the mast step position. This greatly affects mast bend on keel stepped masts. For a stronger bend and less rake, move the mast butt aft. For more rake and less bend (probably what you need to try), move the mast step forward a bit. If neither of these help, you may be off to have your headstay shortened and this means it is too long. This is likely not the case, but it is a possibility.

Keep in mind….A mast should have a slight aft rake bias along with a small amount of mast bend. This is quite normal. You can send us a picture if you’d like a second opinion on if it is over-bent. Having said all of that, even if you remove all of the mast bend, the mast may still pump. This is a design flaw in many spar designs that lots of end users have experienced. This can be remedied by redesigning the stay lay out. Is there a place for a staysail stay and/ or runner backstays? If so add them. Is there a place for a baby stay? If not, that may be a consideration.

Thanks again and I hope that helps.

Hi, I have a 48 foot yawl with a 7/8 fractional rig, is the tuning procedure the same as a masthead rig? I seem to have trouble getting aft rake and proper headstay tension. Also, is there a particular tension number the upper shrouds should have? many thanks in advance

Hi Bill, thanks for taking the time. 7/8 is very close and I would treat it like a masthead rig, especially if the none of the spreaders are aft swept. Tesnsion the headstay using the backstay(s). This should pull the top of the mast aft. If there are any other forward stays, i.e. stay sail stay, forward lowers, or anything else that could be holding the mast forward, go ahead and loosen those completely. You then may need to tighten the Tri-attic (the stay that connects the top of the mizzen and top of the main) if present. OR if the mizzen needs more rake too, then lossen all forward stays and pull it back using the available aft stays for this as well.

Hope this helps and please email us and send some pictures if you need more help.

I have a 1972 Morgan 27, which has both forward and after lower shrouds. I wish to remove the forward lowers so I can trim a 110% jib inside the stays. I see a lot of boats without forward lowers and think this will work OK, but wonder if I should increase the size of the aft lowers and beef up the chain plates. Any suggestions?

THANKS FOR YOUR INPUT. I AM GOING TO REMOVE THEM ANYWAY AND SEE WHAT HAPPENS. “HOLD MY BEER, WATCH THIS….” FAMOUS LAST WORDS.

Lol! Good luck. Call us if you need assistance.

I have rod rigging on my Beneteau 32s5

Any other guidance on tuning them vs wire rigging

Hi and thanks for commenting.

Just follow the guidelines in the write up. The over all goal is that the mast needs to be straight and in-column when looking at it from side to side.

Fore and aft, the mast should show a very slight lean aft. Depending on whether or not the spreaders are in-line or aft swept; you should also see some slight bend if there is any aft sweep to the spreaders just from the tension of the uppers.

A Rod stay tends to run a bit tighter than wire, so keep that in mind.

For racing, ideally once the static tune at the dock (the part we just talked about) is done, go out and sail tune. Do this by going hard on the wind and checking to see if the leeward shrouds are just starting to dance, this is ideal. If they are swaying about they are too loose for the current conditions. If the leeward shrouds are tight, they may be a touch to tight. Tension and loosen as needed; count what you did and to what shroud, then tack and do the same to the other side.

ALWAYS secure the turnbuckles when you are finished adjusting them.

- Pingback: Tuning a Sailboat Mast | ChesapeakeLiving.com

- Pingback: Rig Tuned | middlebaysailing

Wow, I would hate to be charged by her for three trips up the rig and forget the screw driver the rubber plugs that are sacraficial and replaced everytime removed just to clean the stainless 1×19 rigging.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Lost your password?

Review Cart

No products in the cart.

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

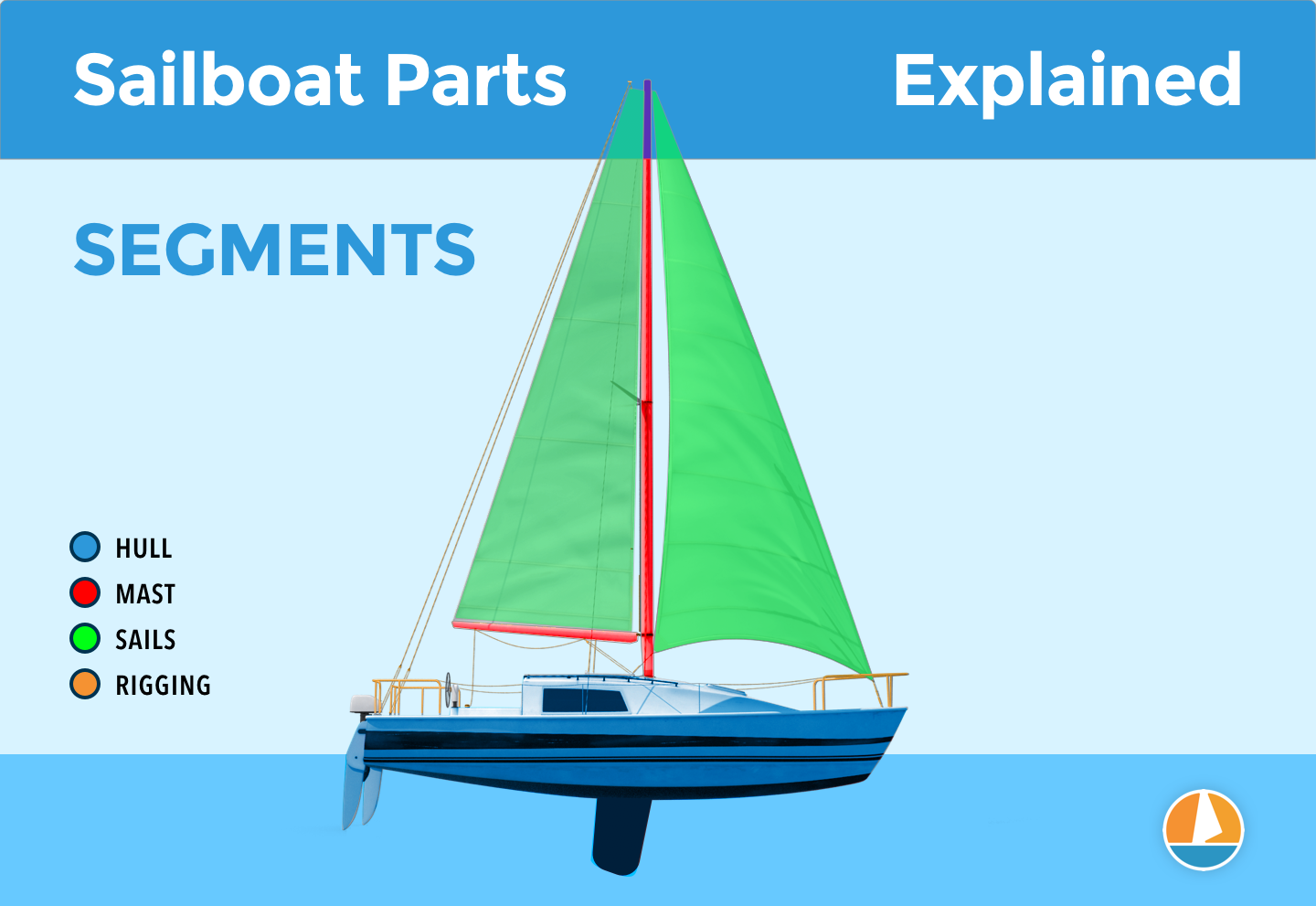

Sailboat Rigging: A Guide to Achieve Smooth Sailing Bliss

Understanding sailboat rigging.

Sailboat rigging is the process of setting up the sails, ropes, and associated components of a sailboat to enable it to harness the power of the wind and navigate the waters efficiently. It is a crucial aspect of sailing that directly impacts the performance, safety, and overall experience on the water.

Proper sailboat rigging involves a combination of knowledge, skill, and attention to detail. Each component plays a specific role and must be correctly installed, adjusted, and maintained to ensure optimal performance. Understanding the fundamentals of sailboat rigging is essential for both seasoned sailors and beginners alike.

The Importance of Proper Sailboat Rigging

Proper sailboat rigging is essential for several reasons. Firstly, it directly affects the performance of your sailboat. Well-rigged sails and ropes allow you to harness the wind effectively, resulting in better speed, maneuverability, and control. On the other hand, poorly rigged sails can lead to reduced performance and frustrating sailing experiences.

Secondly, sailboat rigging is crucial for safety. A well-rigged sailboat ensures that the mast, rigging components, and sails are secure and can withstand the forces of wind and waves. It minimizes the risk of equipment failure, such as broken masts or snapped rigging, which can lead to accidents or stranded situations on the water.

Lastly, proper sailboat rigging enhances the overall enjoyment of sailing. When your rigging is set up correctly, you can focus on the beauty of the sea, the thrill of the wind, and the joy of gliding through the water. It allows you to fully immerse yourself in the experience and achieve a state of sailing bliss.

Types of Sailboat Rigging Systems

Sailboat rigging systems can vary depending on the type of sailboat and its intended use. The two main types of rigging systems are the masthead rig and the fractional rig.

The masthead rig is a traditional rigging configuration where the mast extends to the top of the sailboat, and the forestay is attached near the masthead. This rigging system is commonly found on cruising sailboats and provides excellent downwind performance and stability.

On the other hand, the fractional rig is a more modern design where the forestay is attached at a point below the masthead, typically around two-thirds of the way up the mast. This configuration is often used in racing sailboats as it allows for better upwind performance and increased maneuverability.

Understanding the different rigging systems is essential as it influences the setup and tuning of the sailboat rigging. Each system requires specific adjustments and considerations to achieve optimal performance.

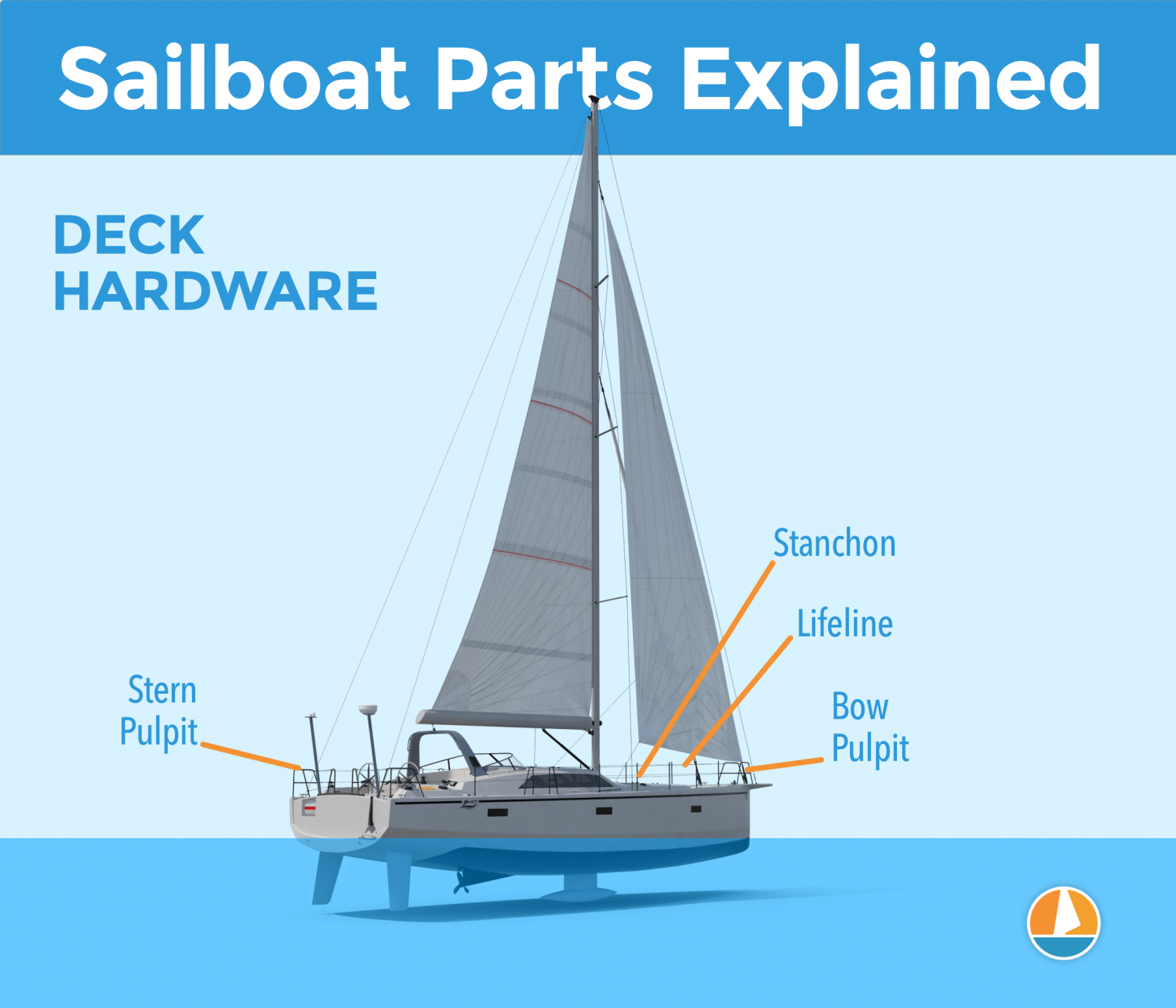

Essential Components of Sailboat Rigging

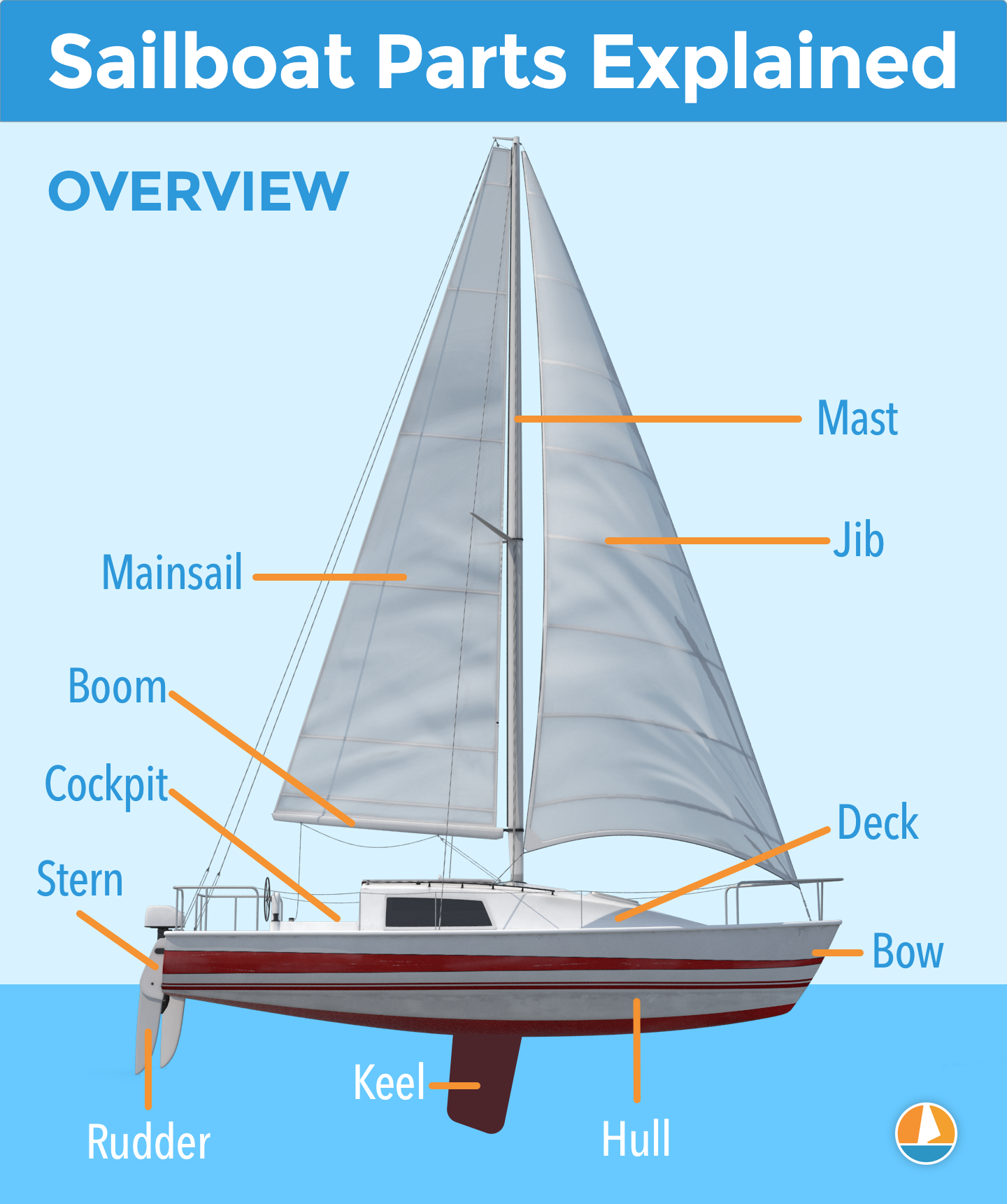

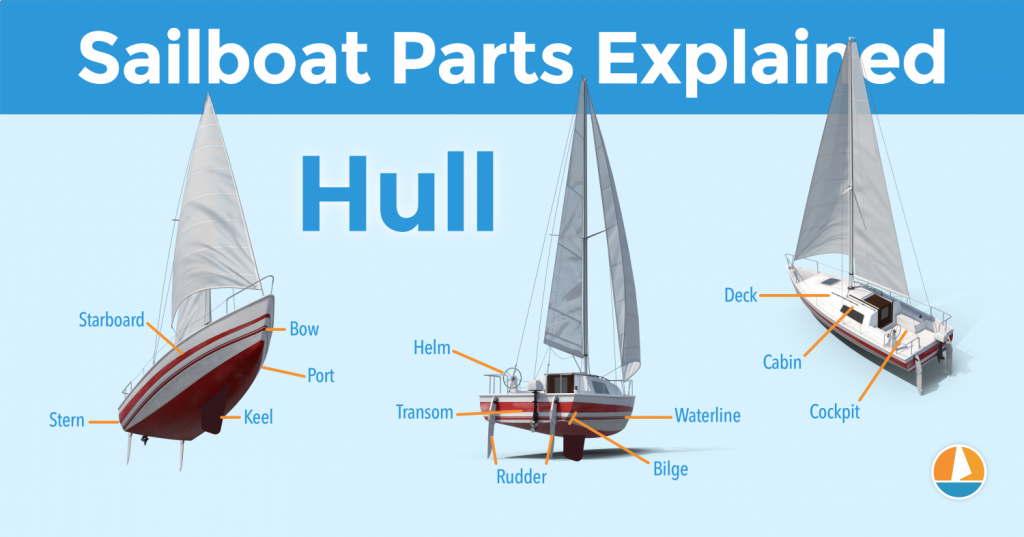

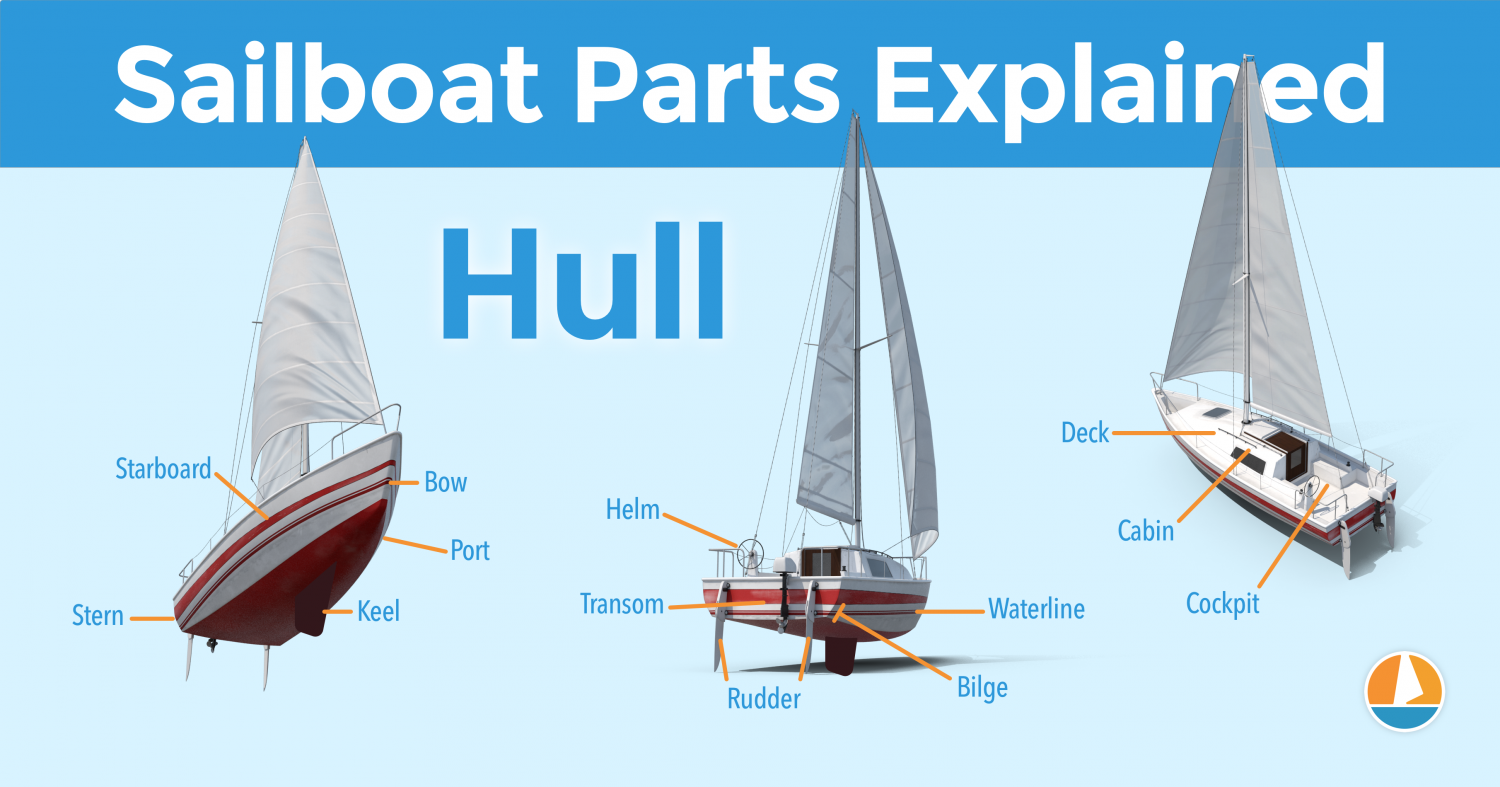

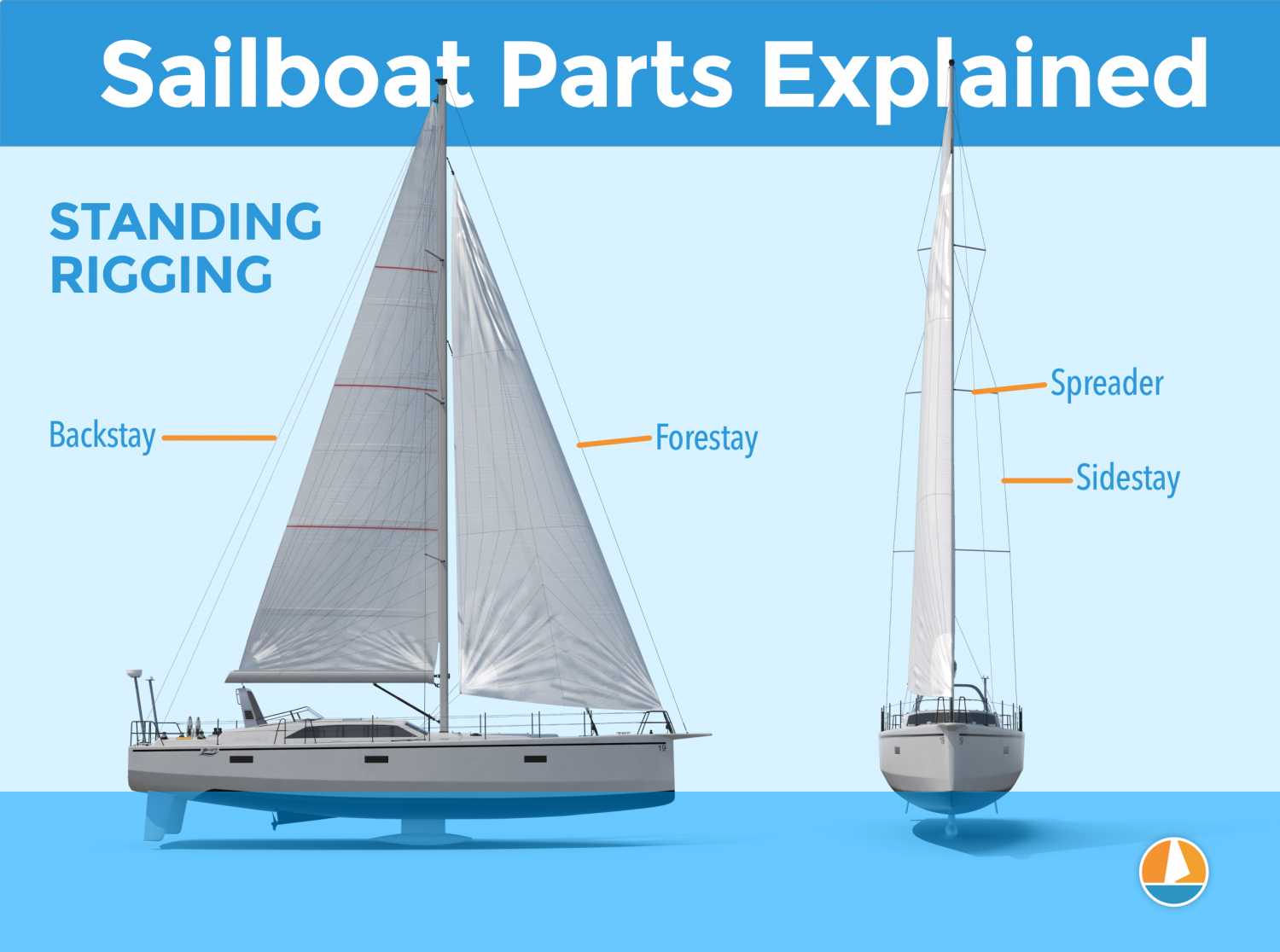

Sailboat rigging consists of several essential components that work together to support the mast, control the shape of the sails, and enable efficient sail handling. These components include the mast, shrouds, stays, and halyards.

The mast is the vertical structure that supports the sails and rigging. It is typically made of aluminum or carbon fiber and must be strong, lightweight, and properly secured to the sailboat. The mast is connected to the hull through a step at the base, which distributes the loads from the rigging throughout the boat.

Shrouds and stays are the primary supporting elements that hold the mast in place and provide lateral and fore-aft stability. Shrouds are attached to the mast at various points and extend out to the sides of the sailboat, while stays run from the mast to the bow or stern of the boat. These components are typically made of stainless steel wire or synthetic fibers and must be tensioned correctly to maintain the integrity of the rig.

Halyards are ropes or wires used to raise and lower the sails. They run from the masthead to the sail and allow for the adjustment of sail shape and size. Proper halyard tension is crucial for controlling the shape of the sails and optimizing their performance in different wind conditions.

Each of these components plays a vital role in sailboat rigging, and understanding their functions and proper installation is key to achieving smooth sailing.

Inspecting and Maintaining Sailboat Rigging

Regular inspection and maintenance of sailboat rigging are essential to ensure its longevity, reliability, and safety. Before setting sail, it is crucial to conduct a thorough visual inspection of all rigging components.

Start by checking the mast for any signs of damage, such as cracks, corrosion, or loose fittings. Inspect the shrouds and stays for any broken strands, kinks, or signs of wear. Pay close attention to the connections between the rigging components and the mast, ensuring they are secure and free from any potential issues.

Next, inspect the halyards for fraying, excessive wear, or damage. Check the blocks, cleats, and winches associated with the halyards to ensure they are functioning properly and are appropriately lubricated.

Additionally, check the tension of the rigging by gently pushing on the shrouds and stays. They should have a slight amount of tension, but not be overly loose or overly tight. If any adjustments are needed, refer to the sailboat’s rigging guide or consult with a professional rigger.

Regular maintenance tasks for sailboat rigging include cleaning, lubricating, and replacing worn-out components. Cleaning the rigging with fresh water and mild soap helps remove salt and dirt buildup, preventing corrosion and extending the lifespan of the rigging. Lubricating moving parts, such as blocks and turnbuckles, with appropriate marine-grade lubricants helps ensure smooth operation and prevents rust.

It is important to note that if any significant damage or wear is detected during inspection, it is best to consult with a professional rigger for further assessment and repair.

Common Sailboat Rigging Problems and How to Troubleshoot Them

Despite careful inspection and maintenance, sailboat rigging problems can still occur. Understanding common issues and their troubleshooting techniques is essential for every sailor.

One common problem is rigging stretch, which can lead to reduced performance and compromised safety. Rigging stretch occurs when the shrouds and stays elongate over time, causing the mast to lose its proper shape and tension. To address this issue, adjust the rigging tension using the turnbuckles or tensioning devices provided. Refer to the sailboat’s rigging guide for specific instructions on proper tensioning.

Another common problem is rigging fatigue, especially in older sailboats or those exposed to harsh conditions. Rigging fatigue is characterized by broken strands, kinks, or signs of wear. If fatigue is detected, it is crucial to replace the affected rigging components promptly to avoid potential equipment failure. Consult with a professional rigger to ensure proper replacement and rigging setup.

Improper sail trim is another issue that can affect the performance of your sailboat. When the sails are not trimmed correctly, they can become overpowered or lose their shape, resulting in reduced speed and control. Experiment with different sail trim settings, such as halyard tension, sheet tension, and traveler position, to achieve the optimal sail shape for different wind conditions. Practice and experience will help you develop a keen eye for proper sail trim.

Upgrading and Optimizing Sailboat Rigging

Upgrading and optimizing your sailboat rigging can significantly improve performance, safety, and overall sailing experience. There are several areas where upgrades can be considered, depending on your sailboat’s design and intended use.

One common upgrade is replacing wire rigging with synthetic rigging, such as Dyneema or Spectra. Synthetic rigging offers several advantages, including reduced weight, increased strength, and lower maintenance requirements. However, it is crucial to consult with a professional rigger to ensure proper installation and tuning of synthetic rigging.

Another upgrade option is replacing older blocks and pulleys with modern, low-friction alternatives. High-quality blocks with ball bearings or roller bearings can significantly reduce friction and make sail handling smoother and more efficient. Upgrading winches and cleats to larger or more powerful models can also enhance control and ease of use.

Additionally, optimizing your sailboat rigging for specific sailing conditions can improve performance. This may involve adjusting the rig tension, changing the position of the mast rake, or experimenting with different sail combinations. Consulting with experienced sailors or professional riggers can provide valuable insights and recommendations for optimizing your rigging setup.

Hiring a Professional Rigger for Sailboat Rigging

While basic sailboat rigging tasks can be performed by experienced sailors, complex rigging projects or major upgrades are best left to professional riggers. Hiring a professional rigger ensures that the rigging is installed, adjusted, and maintained correctly, minimizing the risk of equipment failure and maximizing the performance of your sailboat.

Professional riggers have the knowledge, expertise, and specialized tools to handle various rigging projects, from simple replacements to complete rig overhauls. They can assess the condition of your current rigging, recommend necessary upgrades or repairs, and provide valuable advice on rig tuning and optimization.

When hiring a professional rigger, it is essential to do thorough research and choose a reputable and experienced individual or company. Seek recommendations from fellow sailors, check online reviews, and inquire about their certifications and qualifications. A reliable professional rigger will work closely with you to understand your sailboat’s specific requirements and ensure that the rigging is tailored to your needs.

Safety Considerations for Sailboat Rigging

Safety should always be a top priority when it comes to sailboat rigging. Here are some important safety considerations to keep in mind:

- Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment, such as a life jacket and harness, when working on the sailboat rigging, especially at heights or in challenging conditions.

- Use proper lifting techniques and equipment when handling heavy rigging components to prevent injuries.

- Be mindful of your surroundings and the potential hazards associated with sailboat rigging, such as moving parts, sharp edges, or overhead obstructions.

- Regularly inspect and maintain safety equipment, such as lifelines and jacklines, to ensure they are in good condition and properly secured.

- Follow manufacturer guidelines and recommended practices for rigging installation, adjustment, and maintenance.

- Stay updated on current safety standards and regulations related to sailboat rigging.

By prioritizing safety and adhering to these considerations, you can enjoy smooth sailing adventures with peace of mind.

Conclusion: Enjoying Smooth Sailing with Well-Maintained Rigging

Mastering the art of sailboat rigging opens up a world of endless possibilities and pure sailing bliss. By understanding the different types of rigging systems, essential components, and proper maintenance techniques, you can achieve optimal performance, safety, and enjoyment on the water.

Regular inspection, maintenance, and troubleshooting of sailboat rigging are essential to ensure its longevity and reliability. Upgrading and optimizing your rigging can further enhance your sailing experience and unlock new levels of performance.

While basic rigging tasks can be performed by sailors, complex projects or major upgrades are best left to professional riggers. Hiring a reputable and experienced rigger ensures that your rigging is expertly installed, adjusted, and maintained.

Remember to prioritize safety at all times and follow recommended practices to minimize risks associated with sailboat rigging.

So, set sail, embrace the wind, and experience the bliss of smooth sailing with well-maintained sailboat rigging. May your adventures on the water be filled with joy, excitement, and the sheer beauty of the sea.

- Mastering the Mast: A Comprehensive Dive into the World of Sailboat Masts and Their Importance

A mast is not just a tall structure on a sailboat; it's the backbone of the vessel, holding sails that catch the wind, driving the boat forward. Beyond function, it's a symbol of adventure, romance, and humanity's age-old relationship with the sea.

The Rich Tapestry of Sailboat Mast History

From the simple rafts of ancient civilizations to the majestic ships of the Renaissance and the agile sailboats of today, masts have undergone significant evolution.

- The Humble Beginnings : Early masts were basic structures, made from whatever wood was available. These rudimentary poles were designed to support basic sails that propelled the boat forward.

- The Age of Exploration : As ships grew in size and began journeying across oceans, the demands on masts increased. They needed to be taller, stronger, and able to support multiple sails.

- Modern Innovations : Today's masts are feats of engineering, designed for efficiency, speed, and durability.

A Deep Dive into Types of Boat Masts

There's no 'one size fits all' in the world of masts. Each type is designed with a specific purpose in mind.

- Keel Stepped Mast : This is the traditional choice, where the mast runs through the deck and extends into the keel. While providing excellent stability, its integration with the boat's structure makes replacements and repairs a task.

- Deck Stepped Mast : Gaining popularity in modern sailboats, these masts sit atop the deck. They might be perceived as less stable, but advancements in boat design have largely addressed these concerns.

Materials and Their Impact

The choice of material can profoundly affect the mast's weight, durability, and overall performance.

- Aluminum : Lightweight and resistant to rust, aluminum masts have become the industry standard for most recreational sailboats.

- Carbon Fiber : These masts are the sports cars of the sailing world. Lightweight and incredibly strong, they're often seen on racing boats and high-performance vessels.

- Wood : Wooden masts carry the romance of traditional sailing. They're heavier and require more maintenance but offer unparalleled aesthetics and a classic feel.

Anatomy of a Sail Mast

Understanding the various components can greatly improve your sailing experience.

- Masthead : Sitting atop the mast, it's a hub for various instruments like wind indicators and lights.

- Spreaders : These are essential for maintaining the mast's stability and optimizing the angle of the sails.

- Mast Steps and Their Critical Role : Climbing a mast, whether for repairs, adjustments, or simply the thrill, is made possible by these "rungs." Their design and placement are paramount for safety.

Deck vs. Yacht Masts

A common misconception is that all masts are the same. However, the requirements of a small deck boat versus a luxury yacht differ drastically.

- Yacht Masts : Designed for grandeur, these masts are equipped to handle multiple heavy sails, sophisticated rigging systems, and the weight and balance demands of a large vessel.

- Sailboat Masts : Engineered for agility, they prioritize speed, wind optimization, and quick adjustments.

Maintenance, Repairs, and the Importance of Both

Seawater, winds, and regular wear and tear can take their toll on your mast.

- Routine Maintenance : Regular checks for signs of corrosion, wear, or structural issues can prolong your mast's life. Using protective coatings and ensuring moving parts are well-lubricated is crucial.

- Common Repairs : Over time, parts like spreaders, stays, or even the mast steps might need repair or replacement. Regular inspections can spot potential problems before they escalate.

Read our top notch articles on topics such as sailing, sailing tips and destinations in our Magazine .

Check out our latest sailing content:

Costing: The Investment Behind the Mast

While the thrill of sailing might be priceless, maintaining the mast comes with its costs.

- Regular Upkeep : This is an ongoing expense, but think of it as insurance against larger, more costly repairs down the line.

- Repairs : Depending on severity and frequency, repair costs can stack up. It's always advisable to address issues promptly to avoid more significant expenses later.

- Complete Replacement : Whether due to extensive damage or just seeking an upgrade, replacing the mast is a significant investment. Consider factors like material, type, and labor when budgeting.

Upgrading Your Mast: Why and How

There comes a time when every sailor contemplates upgrading their mast. It might be for performance, compatibility with new sail types, or the allure of modern materials and technology.

- Performance Boosts : New masts can offer better aerodynamics, weight distribution, and responsiveness.

- Material Upgrades : Shifting from an old wooden mast to a modern aluminum or carbon fiber one can drastically change your sailing experience.

- Compatibility : Modern sails, especially those designed for racing or specific weather conditions, might necessitate a mast upgrade.

The Impact of Weather on Masts

Weather conditions significantly influence the longevity and performance of your mast. From strong winds to salty sea sprays, each element poses unique challenges. Regularly washing the mast, especially after sailing in saltwater, can help prevent the onset of corrosion and wear.

Customization and Personal Touches

Every sailor has a unique touch, and this extends to the mast. Whether it's intricate carvings on wooden masts, personalized masthead designs, or innovative rigging solutions, customization allows sailors to make their vessel truly their own.

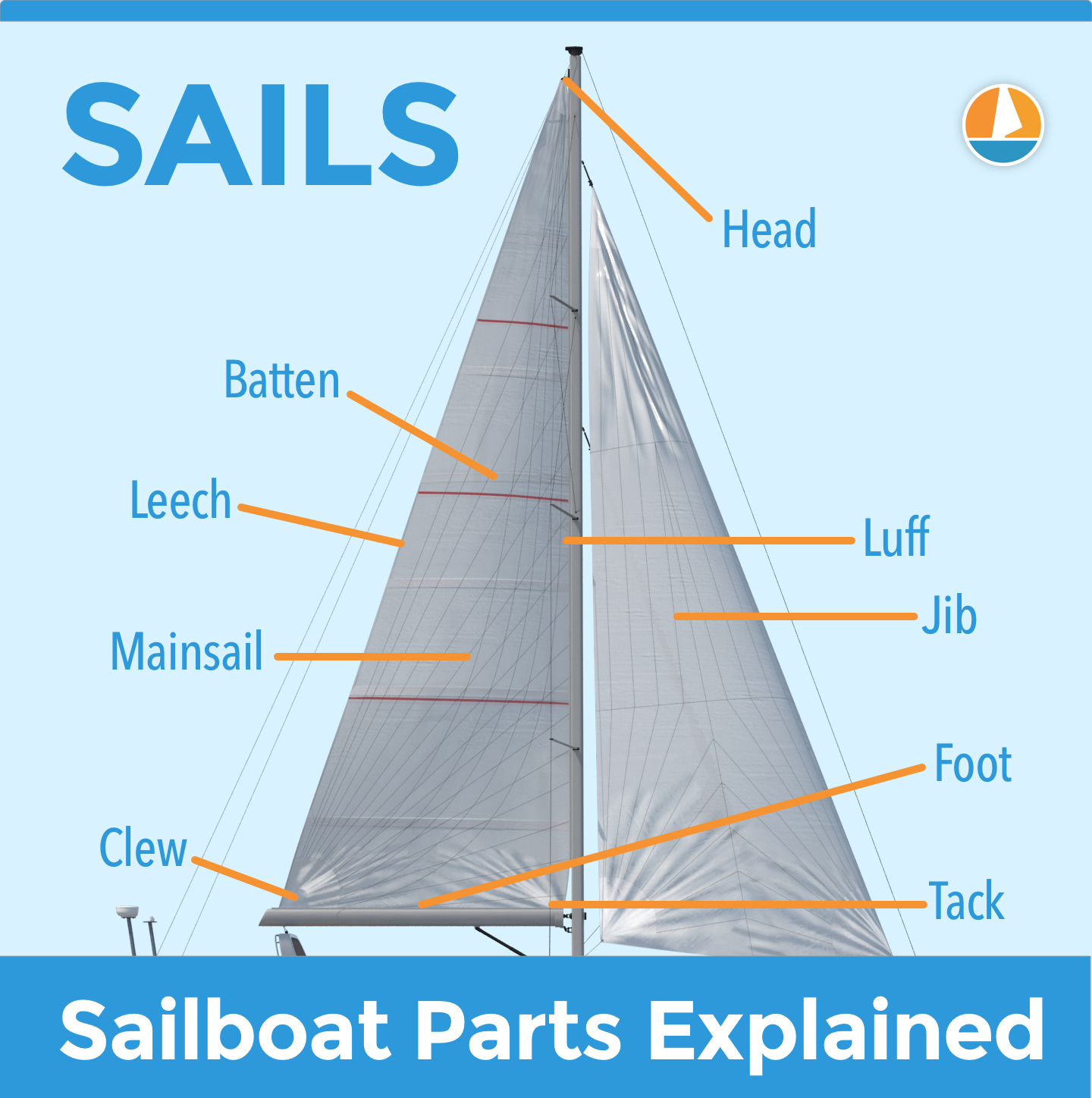

The Role of Sails in Mast Design

It's not just about the mast; the type and size of sails greatly influence mast design. From the full-bellied spinnakers to the slender jibs, each sail requires specific support, tension, and angle, dictating the rigging and structure of the mast.

Safety First: The Role of Masts in Overboard Incidents

A mast isn't just for sailing; it plays a crucial role in safety. In overboard situations, the mast, especially when fitted with steps, can be a lifeline, allowing sailors to climb back onto their boat. Its visibility also aids in search and rescue operations.

The Rise of Eco-Friendly Masts

As the world grows more eco-conscious, the sailing community isn't far behind. New materials, designed to be environmentally friendly, are making their way into mast production. They aim to provide the strength and durability of traditional materials while reducing the environmental footprint.

The Intricate World of Rigging

The mast serves as the anchor for a complex system of ropes, pulleys, and cables – the rigging. This network, when fine-tuned, allows sailors to adjust sails for optimal wind capture, maneuverability, and speed. Mastery over rigging can elevate a sailor's experience and prowess significantly.

Historical Significance: Masts in Naval Warfare

In historical naval battles, the mast played a pivotal role. Damaging or destroying an enemy's mast was a strategic move, crippling their mobility and rendering them vulnerable. The evolution of masts in naval ships offers a fascinating glimpse into maritime warfare tactics of yesteryears.

The Science Behind Mast Vibrations

Ever noticed your mast humming or vibrating in strong winds? This phenomenon, known as aeolian vibration, arises from the interaction between wind and the mast's

structure. While it can be a mesmerizing sound, unchecked vibrations over time can lead to wear and potential damage.

Future Trends: What Lies Ahead for Sailboat Masts

With technological advancements, the future of masts is bright. Concepts like retractable masts, integrated solar panels, and smart sensors for real-time health monitoring of the mast are on the horizon. These innovations promise to redefine sailing in the years to come.

Paying Homage: Celebrating the Mast

Across cultures and ages, masts have been celebrated, revered, and even worshipped. From the Polynesians who viewed them as spiritual totems, to modern sailors tattooing mast symbols as badges of honor, the mast, in its silent grandeur, continues to inspire awe and respect.

Conclusion: The Mast’s Place in Sailing

In the grand scheme of sailing, the mast holds a place of reverence. It's not just a structural necessity; it's a testament to human ingenuity, our quest for exploration, and the sheer love of the sea.

How often should I inspect my mast?

At least twice a year, preferably before and after sailing season.

Can I handle repairs myself?

Minor repairs, yes. But for major issues, it's best to consult a professional.

Is there an average lifespan for a mast?

With proper care, masts can last decades. Material and maintenance quality play a huge role.

How do I know if it's time to replace my mast?

Constant repairs, visible wear, and decreased performance are indicators.

What's the most durable mast material?

Carbon fiber is incredibly strong and durable, but aluminum also offers excellent longevity.

So what are you waiting for? Take a look at our range of charter boats and head to some of our favourite sailing destinations.

Mast Queries Answered

I am ready to help you with booking a boat for your dream vacation. contact me..

Denisa Nguyenová

Standing Rigging (or ‘Name That Stay’)

Published by rigworks on november 19, 2019.

Question: When your riggers talk about standing rigging, they often use terms I don’t recognize. Can you break it down for me?

From the Rigger: Let’s play ‘Name that Stay’…

Forestay (1 or HS) – The forestay, or headstay, connects the mast to the front (bow) of the boat and keeps your mast from falling aft.

- Your forestay can be full length (masthead to deck) or fractional (1/8 to 1/4 from the top of the mast to the deck).

- Inner forestays, including staysail stays, solent stays and baby stays, connect to the mast below the main forestay and to the deck aft of the main forestay. Inner forestays allow you to hoist small inner headsails and/or provide additional stability to your rig.

Backstay (2 or BS) – The backstay runs from the mast to the back of the boat (transom) and is often adjustable to control forestay tension and the shape of the sails.

- A backstay can be either continuous (direct from mast to transom) or it may split in the lower section (7) with “legs” that ‘V’ out to the edges of the transom.

- Backstays often have hydraulic or manual tensioners built into them to increase forestay tension and bend the mast, which flattens your mainsail.

- Running backstays can be removable, adjustable, and provide additional support and tuning usually on fractional rigs. They run to the outer edges of the transom and are adjusted with each tack. The windward running back is in tension and the leeward is eased so as not to interfere with the boom and sails.

- Checkstays, useful on fractional rigs with bendy masts, are attached well below the backstay and provide aft tension to the mid panels of the mast to reduce mast bend and provide stabilization to reduce the mast from pumping.

Shrouds – Shrouds support the mast from side to side. Shrouds are either continuous or discontinuous .

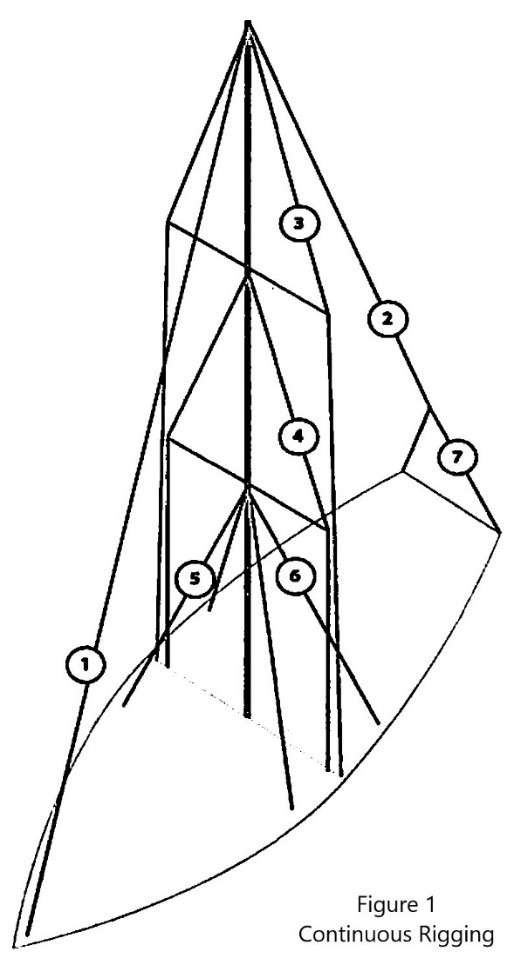

Continuous rigging, common in production sailboats, means that each shroud (except the lowers) is a continuous piece of material that connects to the mast at some point, passes through the spreaders without terminating, and continues to the deck. There may be a number of continuous shrouds on your boat ( see Figure 1 ).

- Cap shrouds (3) , sometimes called uppers, extend from masthead to the chainplates at the deck.

- Intermediate shrouds (4) extend from mid-mast panel to deck.

- Lower shrouds extend from below the spreader-base to the chainplates. Fore- (5) and Aft-Lowers (6) connect to the deck either forward or aft of the cap shroud.

Discontinuous rigging, common on high performance sailboats, is a series of shorter lengths that terminate in tip cups at each spreader. The diameter of the wire/rod can be reduced in the upper sections where loads are lighter, reducing overall weight. These independent sections are referred to as V# and D# ( see Figure 2 ). For example, V1 is the lowest vertical shroud that extends from the deck to the outer tip of the first spreader. D1 is the lowest diagonal shroud that extends from the deck to the mast at the base of the first spreader. The highest section that extends from the upper spreader to the mast head may be labeled either V# or D#.

A sailboat’s standing rigging is generally built from wire rope, rod, or occasionally a super-strong synthetic fibered rope such as Dyneema ® , carbon fiber, kevlar or PBO.

- 1×19 316 grade stainless steel Wire Rope (1 group of 19 wires, very stiff with low stretch) is standard on most sailboats. Wire rope is sized/priced by its diameter which varies from boat to boat, 3/16” through 1/2″ being the most common range.

- 1×19 Compact Strand or Dyform wire, a more expensive alternative, is used to increase strength, reduce stretch, and minimize diameter on high performance boats such as catamarans. It is also the best alternative when replacing rod with wire.

- Rod rigging offers lower stretch, longer life expectancy, and higher breaking strength than wire. Unlike wire rope, rod is defined by its breaking strength, usually ranging from -10 to -40 (approx. 10k to 40k breaking strength), rather than diameter. So, for example, we refer to 7/16” wire (diameter) vs. -10 Rod (breaking strength).

- Composite Rigging is a popular option for racing boats. It offers comparable breaking strengths to wire and rod with a significant reduction in weight and often lower stretch.

Are your eyes crossing yet? This is probably enough for now, but stay tuned for our next ‘Ask the Rigger’. We will continue this discussion with some of the fittings/connections/hardware associated with your standing rigging.

Related Posts

Ask the Rigger

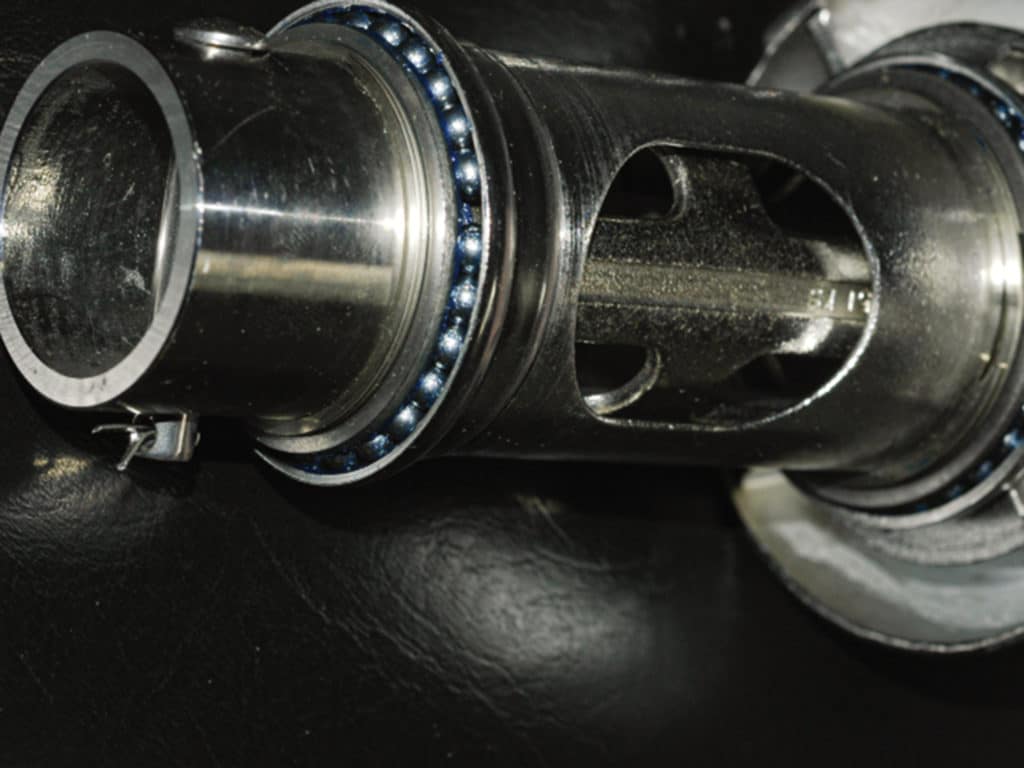

Do your masthead sheaves need replacing.

Question: My halyard is binding. What’s up? From the Rigger: Most boat owners do not climb their masts regularly, but our riggers spend a lot of time up there. And they often find badly damaged Read more…

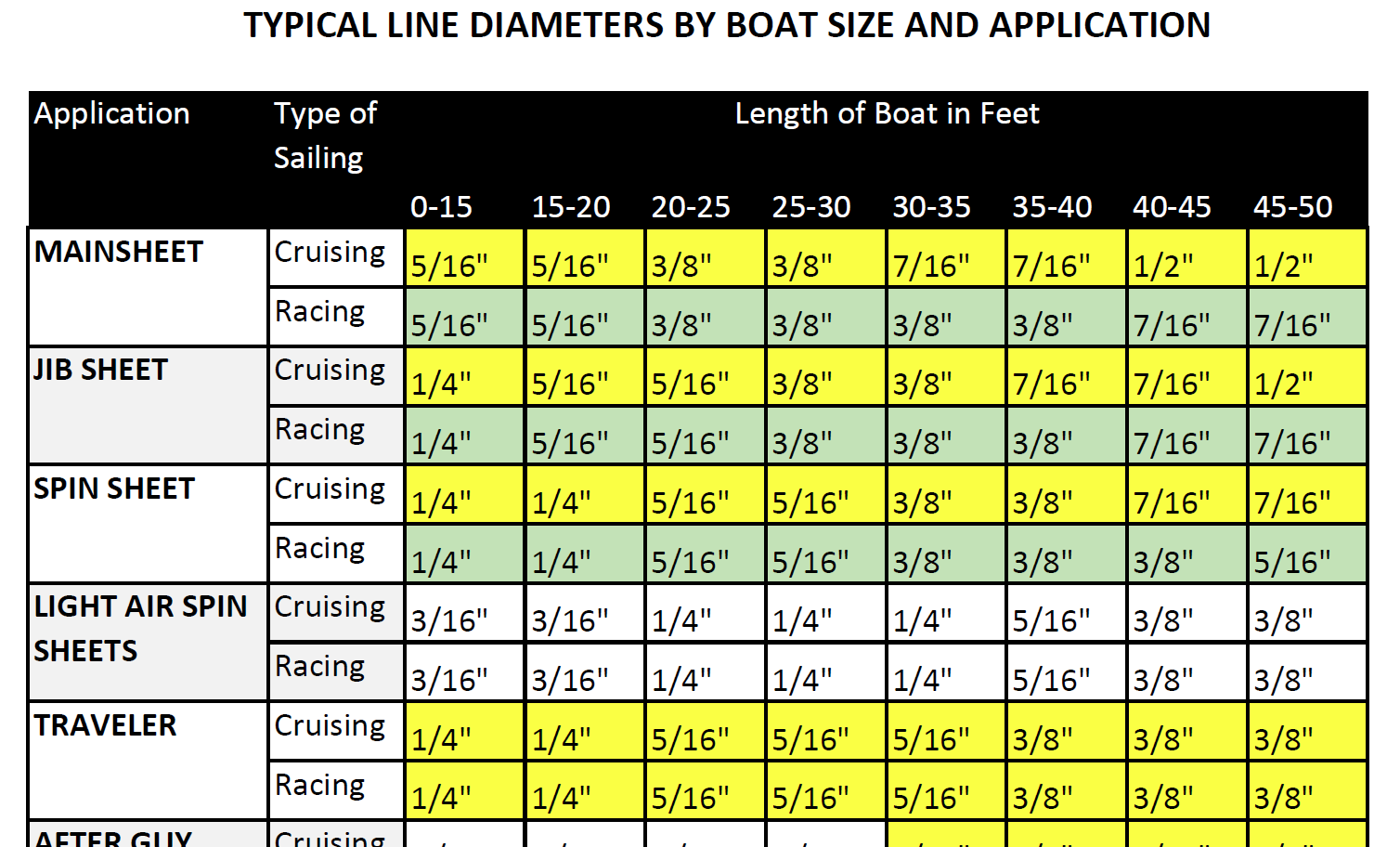

Selecting Rope – Length, Diameter, Type

Question: Do you have guidelines for selecting halyards, sheets, etc. for my sailboat? From the Rigger: First, if your old rope served its purpose but needs replacing, we recommend duplicating it as closely as possible Read more…

Spinlock Deckvest Maintenance

Question: What can I do to ensure that my Spinlock Deckvest is well-maintained and ready for the upcoming season? From the Rigger: We are so glad you asked! Deckvests need to be maintained so that Read more…

No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

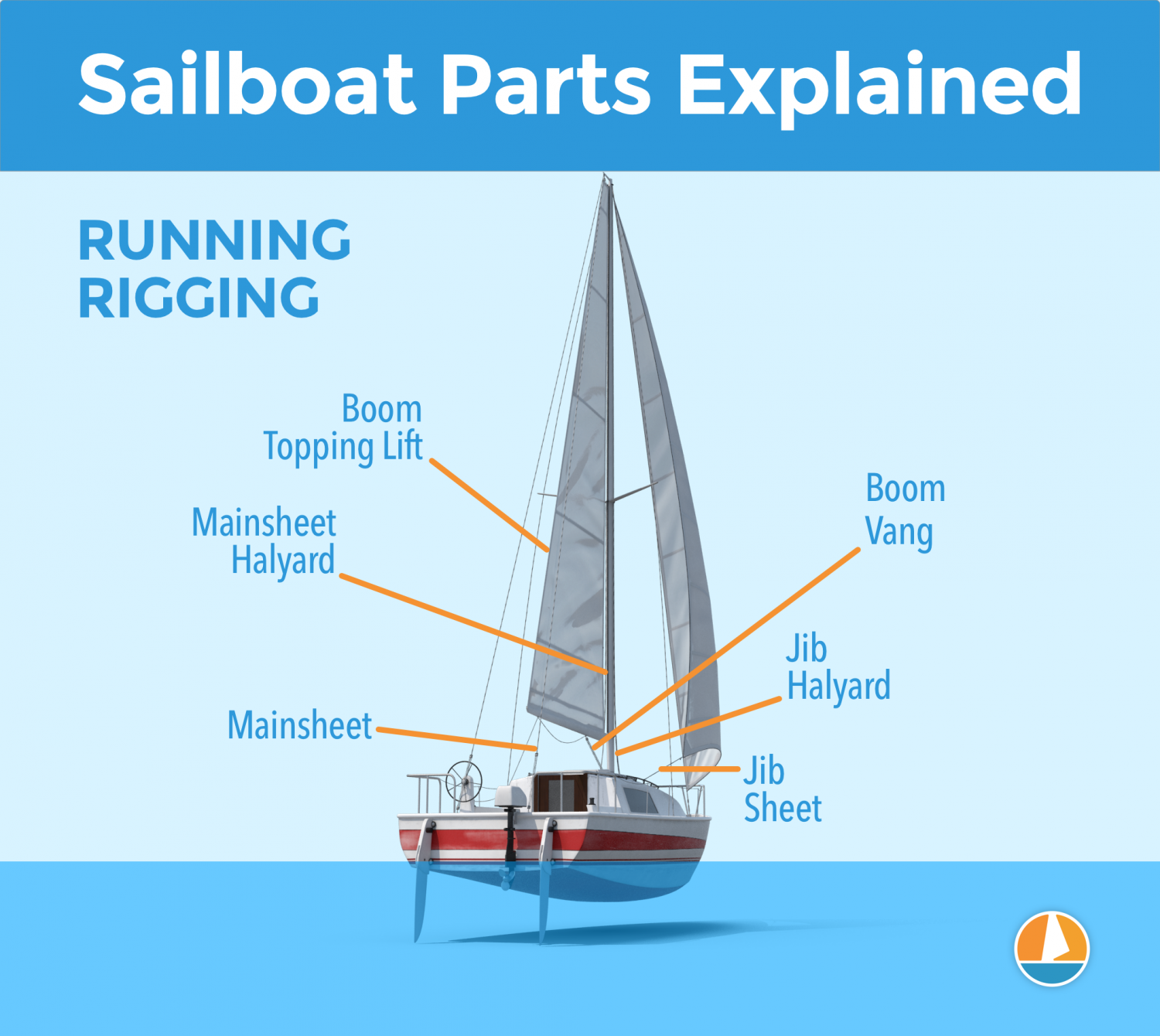

The Running Rigging On A Sailboat Explained

The running rigging on a sailboat consists of all the lines used to hoist, lower, and control the sails and sailing equipment. These lines usually have different colors and patterns to easily identify their function and location on the vessel.

Looking at the spaghetti of lines with different colors and patterns might get your head spinning. But don’t worry, it is actually pretty simple. Each line on a sailboat has a function, and you’ll often find labels describing them in the cockpit and on the mast.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through the functions of every component of the running rigging. We’ll also look at the hardware we use to operate it and get up to speed on some of the terminology.

The difference between standing rigging and running rigging

Sometimes things can get confusing as some of our nautical terms are used for multiple items depending on the context. Let me clarify just briefly:

The rig or rigging on a sailboat is a common term for two parts, the standing , and the running rigging.

- The standing rigging consists of wires supporting the mast on a sailboat and reinforcing the spars from the force of the sails when sailing. Check out my guide on standing rigging here!

- The running rigging consists of the halyards, sheets, and lines we use to hoist, lower, operate and control the sails on a sailboat which we will explore in this guide.

The components of the running rigging

Knowing the running rigging is an essential part of sailing, whether you are sailing a cruising boat or crewing on a large yacht. Different types of sailing vessels have different amounts of running rigging.

For example, a sloop rig has fewer lines than a ketch, which has multiple masts and requires a separate halyard, outhaul, and sheet for its mizzen sail. Similarly, a cutter rig needs another halyard and extra sheets for its additional headsail.

You can dive deeper and read more about Sloop rigs, Ketch Rigs, Cutter rigs, and many others here .

Take a look at this sailboat rigging diagram:

Lines are a type of rope with a smooth surface that works well on winches found on sailboats. They come in various styles and sizes and have different stretch capabilities.

Dyneema and other synthetic fibers have ultra-high tensile strength and low stretch. These high-performance lines last a long time, and I highly recommend them as a cruiser using them for my halyards.

A halyard is a line used to raise and lower the sail. It runs from the head of the sail to the masthead through a block and continues down to the deck. Running the halyard back to the cockpit is common, but many prefer to leave it on the mast.

Fun fact: Old traditional sailboats sometimes used a stainless steel wire attached to the head of the sail instead of a line!

Jib, Genoa, and Staysail Halyards

The halyard for the headsail is run through a block in front of the masthead. If your boat has a staysail, it needs a separate halyard. These lines are primarily untouched on vessels with a furling system except when you pack the sail away or back up. Commonly referred to as the jib halyard.

Spinnaker Halyard

A spinnaker halyard is basically the same as the main halyard but used to hoist and lower the spinnaker, gennaker, or parasailor.

The spinnaker halyard is also excellent for climbing up the front of the mast, hoisting the dinghy on deck, lifting the outboard, and many other things.

A sheet is a line you use to control and trim a sail to the angle of the wind . The mainsheet controls the angle of the mainsail and is attached between the boom and the mainsheet traveler . The two headsail sheets are connected to the sail’s clew (lower aft corner) and run back to each side of the cockpit.

These are control lines used to adjust the angle and tension of the sail. It is also the line used to unfurl a headsail on a furling system. Depending on what sail you are referring to, this can be the Genoa sheet , the Jib sheet , the Gennaker sheet , etc.

The outhaul is a line attached to the clew of the mainsail and used to adjust the foot tension. It works runs from the mainsail clew to the end of the boom and back to the mast. In many cases, back to the cockpit. On a boat with in-mast furling , this is the line you use to pull the sail out of the mast.

Topping lift

The topping lift is a line attached to the boom’s end and runs through the masthead and down to the deck or cockpit. It lifts and holds the boom and functions well as a spare main halyard. Some types of sailboat rigging don’t use a topping lift for their boom but a boom vang instead. Others have both!

Topping lifts can also be used to lift other spars.

A downhaul is a line used to lower with and typically used to haul the mainsail down when reefing and lowering the spinnaker and whisker poles. The downhaul can also control the tack of an asymmetrical spinnaker, gennaker, or parasailor.

Tweaker and Barber Haul