Friends' sailing adventure ends in a dramatic rescue after a whale sinks their boat in the Pacific

What started as a sailing adventure for one man and three of his friends ended in a dramatic rescue after a giant whale sank his boat, leaving the group stranded in the middle of the Pacific Ocean for hours and with a tale that might just be stranger than fiction.

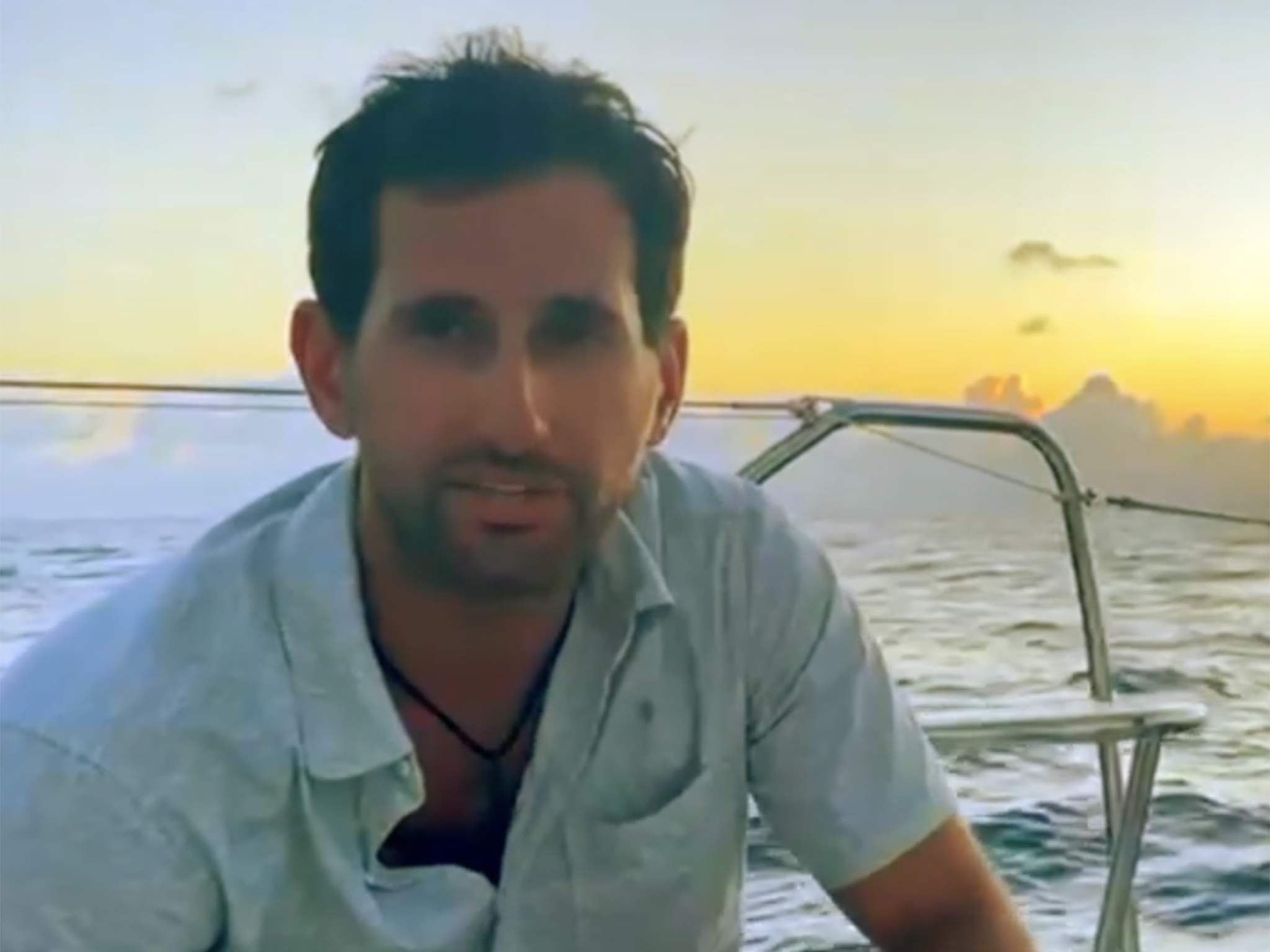

Rick Rodriguez and his friends had been on what was meant to be a weekslong crossing to French Polynesia on his sailboat, Raindancer, when the crisis unfolded just over a week ago.

They had been enjoying some pizza for lunch when they heard a loud bang.

"It just happened in an instant. It was just a very violent impact with some crazy-sounding noises and the whole boat shook," Rodriguez told NBC's "TODAY" show in an interview that aired Wednesday.

"It sounded like something broke and we immediately looked to the side and we saw a really big whale bleeding,” he said.

The impact was so severe that the boat's propeller was ruptured and the fiberglass around it shattered, sending the vessel into the ocean.

As water began to rush into the boat, the group snapped into survival mode.

"There was just an incredible amount of water coming in, very fast," Rodriguez said.

Alana Litz, a member of the crew, described the ordeal as "surreal."

"Even when the boat was going down, I felt like it was just a scene out of a movie. Like everything was floating," she said.

Rodriguez and his friends acted fast, firing off mayday calls and text messages as they activated a life raft and dinghy.

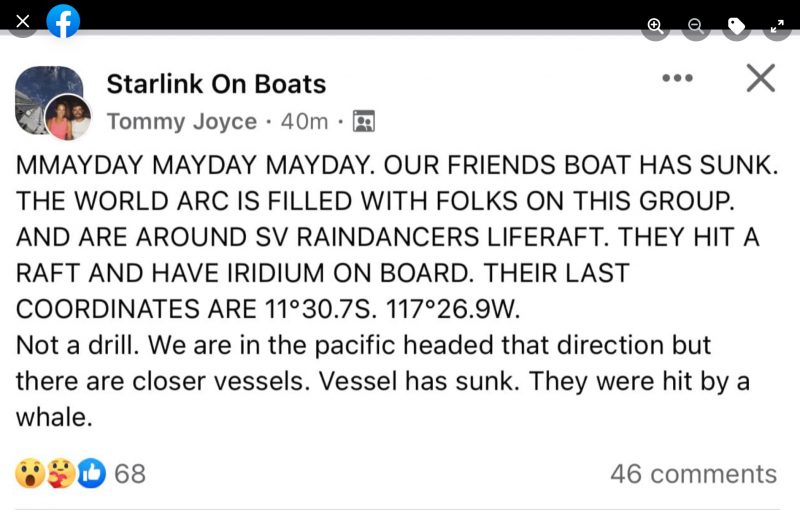

He said he sent a text message to his brother Roger in Miami and to a friend, Tommy Joyce, who was sailing a "buddy boat" in the area as a safety measure.

“Tommy this is no joke," Rodriguez wrote in a text message. "We hit a whale and the ship went down."

"We are in the life raft," he texted his friend. "We need help *ASAP."

Raindancer sank within about 15 minutes, the group said. Their rescue took much longer that, with the four friends out on the open waters for roughly nine hours before they could be sure they would live to tell the tale.

Peruvian officials picked up the group's distress signal and the U.S. Coast Guard was alerted, with its District 11 in Alameda, California, being in charge of U.S. vessels in the Pacific.

Ultimately, it was another sailing vessel, the Rolling Stones, that came to the group's aid after Joyce shared the incident on a Facebook boat watch group.

Geoff Stone, captain of the Rolling Stones, said they were about 60 or 65 miles away when his crew members realized that their vessel was the closest boat.

After searching the waters, they were eventually able to locate the group of friends.

“We were shocked that we found them," Stone said.

The timing of the rescue, which unfolded at night, appeared to be critical as the Stones' crew members were able to see the light from the dinghy bobbing in the darkness.

Rodriguez lost his boat and the group of friends said they also lost their passports and many of their possessions, but they said they were just grateful to be alive.

The severity of the injuries sustained by the whale were not immediately clear.

Kate Wilson, a spokeswoman for the International Whaling Commission, told The Washington Post, which first reported the story, that there have been about 1,200 reports of whales and boats colliding since a worldwide database launched in 2007.

Collisions causing significant damage are rare, the Coast Guard told the outlet. It noted that the last rescue attributed to impact from a whale was the sinking of a 40-foot J-Boat in 2009 off Baja California. The crew in that incident was rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter.

One member of Raindancer's sailing crew, Bianca Brateanu, said the more recent incident, however harrowing, left her feeling more confident in her survival skills.

“This experience made me realize how, you know how capable we are, and how, how skilled we are to manage and cope with situations like this,” she said.

In an Instagram post, Rodriguez said he would remember his boat "for the rest of my life."

"What’s left of my home, the pictures on the wall, belongings, pizza in the oven, cameras, journals, all of it, will forever be preserved by the sea," he said.

"As for me, I had a temporary mistrust in the ocean. But I’m quickly realizing I’m still the same person," Rodriguez wrote. “I often think about the whale who likely lost its life, but is hopefully ok. I'm not sure what my next move will be. But my attraction to the sea hasn’t been shaken."

Chantal Da Silva reports on world news for NBC News Digital and is based in London.

Sam Brock is an NBC News correspondent.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Their Boat Hit a Whale and Sank. The Internet Saved Their Lives.

After the collision in the Pacific Ocean this month, Rick Rodriguez and three other sailors were rescued by a fellow boater, with an assist from a satellite internet signal.

By Mike Ives

When Rick Rodriguez’s sailboat collided with a whale in the middle of the Pacific Ocean earlier this month, it sank within about 15 minutes. But not before he and his three fellow mariners had escaped with essential supplies and cutting-edge communications gear.

One was a pocket-size satellite device that allowed Mr. Rodriguez to call his brother, who was thousands of miles away on land, from a life raft. That call would set in motion a successful rescue effort by other sailors in the area who had satellite internet access on their boats.

“Technology saved our lives,” Mr. Rodriguez later wrote in an account that he typed on his iPhone from the sailboat that had rescued him and his crew.

People involved in the roughly nine-hour rescue say it illustrates how newer satellite technologies, especially Starlink internet systems , operated by the rocket company SpaceX since 2019 , have dramatically improved emergency communication options for sailors stranded at sea — and the people trying to find them.

“All sailors want to help out,” said Tommy Joyce, a friend of Mr. Rodriguez who helped organize the rescue effort from his own sailboat. “But this just makes it so much easier to coordinate and help boaters in distress.”

Starlink’s service gives vessels access to satellite signals that reach oceans and seas around the globe, according to the company. The fee-based connection allows sailors to reach other vessels on their own, instead of relying solely on sending distress signals to government-rescue agencies that use older, satellite-based communication technologies.

But the rapid rescue would not have been possible without the battery-powered satellite device that Mr. Rodriguez used to call his brother. Such devices have only been used by recreational sailors for about a decade, according to the United States Coast Guard. This one’s manufacturer, Iridium, said in a statement that the device is “incredibly popular with the sailing community.”

“The recent adoption of more capable satellite systems now means sailors can broadcast distress to a closed or public chat group, sometimes online, and get an instant response,” said Paul Tetlow, the managing director of the World Cruising Club, a sailing organization whose members participated in the rescue .

A sinking feeling

Whales don’t normally hit boats. In a famous exception, one rammed the whaling vessel Essex as it crisscrossed the Pacific Ocean in 1820, an accident that was among the inspirations for Herman Melville’s 1851 novel “ Moby Dick .”

In Mr. Rodriguez’s case, a whale interrupted a three-week voyage by his 44-foot sailboat, Raindancer , from the Galápagos Islands in Ecuador to French Polynesia. At the time of the impact on March 13, the boat was cruising at about seven miles per hour and its crew was busy eating homemade pizza.

Mr. Rodriguez would later write that making contact with the whale — just as he dipped a slice into ranch dressing — felt like hitting a concrete wall.

Even as the boat sank, “I felt like it was just a scene out of a movie," Alana Litz, a friend of Mr. Rodriguez and one of the sailors on Raindancer, told NBC’s “Today” program last week. The story of the rescue had been reported earlier by The Washington Post .

Raindancer’s hull was reinforced to withstand an impact with something as large and heavy as a cargo container. But the collision created multiple cracks near the stern, Mr. Rodriguez later wrote , and water rose to the floorboards within about 30 seconds.

Minutes later, he and his friends had all escaped from the boat with food, water and other essential supplies. When he looked back, he saw the last 10 feet of the mast sinking quickly. As a line that had been tying the raft to the boat started to come under tension, he cut it with a knife.

That left the Raindancer crew floating in the open ocean, about 2,400 miles west of Lima, Peru, and 1,800 miles southeast of Tahiti.

“The sun began to set and soon it was pitch dark,” Mr. Rodriguez, who was not available for an interview, wrote in an account of the journey that he shared with other sailors. “And we were floating right smack in the middle of the Pacific Ocean with a dinghy and a life raft. Hopeful that we would be rescued soon.”

‘Not a drill’

Before Raindancer sank, Mr. Rodriguez activated a satellite radio beacon that instantly sent a distress alert to coast guard authorities in Peru, the country with search and rescue authority over that part of the Pacific, and the United States, where his boat was registered.

In 2009, a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter rescued a sailboat crew whose vessel had collided with a whale and sank about 70 miles off the coast of Mexico. But Raindancer’s remote location made a rescue like that one impossible. So in the hour after it sank, U.S. Coast Guard officials used decades-old satellite communications technology to contact commercial vessels near the site of the accident.

One vessel responded to say that it was about 10 hours away and willing to divert. But, in the end, that was not necessary because Mr. Rodriguez’s satellite phone call to his brother Roger had already set a separate, successful rescue effort in motion.

Mr. Rodriguez’s brother contacted Mr. Joyce, whose own boat, Southern Cross, had left the Galápagos around the same time and was about 200 miles behind Raindancer when it sank. Because Southern Cross had a Starlink internet connection, it became a hub for a rescue effort that Mr. Joyce, 40, coordinated with other boats using WhatsApp, Facebook and several smartphone apps that track wind speed, tides and boat positions.

“Not a drill,” Mr. Joyce, who works in the biotech industry, often from his boat, wrote on WhatsApp to other sailors who were in the area. “We are in the Pacific headed that direction but there are closer vessels.”

After a flurry of communication, several boats began sailing as quickly as possible toward Raindancer’s last known coordinates.

SpaceX did not respond to an inquiry about the system’s coverage in the Pacific. But Douglas Samp, who oversees the Coast Guard’s search and rescue operations in the Pacific, said in a phone interview that vessels only began using Starlink internet service in the open ocean this year.

Mr. Joyce said that satellite internet had been key to finding boats that were close to the stranded crew.

“They were all using Starlink,” he said, speaking in a video interview from his boat as it sailed to Tahiti. “Can you imagine if we didn’t have access?”

Of course, there was one sailboat captain without a Starlink signal during the rescue: Mr. Rodriguez. After night fell over the Pacific, he and his fellow sailors resorted to the ancient method of sitting in a life raft and hoping for the best.

In the darkness, the wind picked up and flying fish jumped into their dinghy, according to Mr. Rodriguez’s account. Every hour or so, they placed a mayday call on a hand-held radio, hoping that a ship might happen to pass within its range.

None did. But after a few more hours of anxious waiting, they saw the lights of a catamaran and heard the voice of its American captain crackling over their radio. That is when they screamed in relief.

Mike Ives is a general assignment reporter. More about Mike Ives

Around the World With The Times

Our reporters across the globe take you into the field..

A Venezuelan Exodus: About a quarter of the residents of Maracaibo, Venezuela’s second-largest city, have moved away due to economic misery and political repression. More are expected to soon follow .

Why Brazil Banned X: To combat disinformation, Brazil gave one judge broad power to police the internet. Now, after he blocked the social network, some are wondering whether that was a good idea .

How the Tories Lost Britain: Brexit and immigration upended their 14-year reign, setting the stage for a pitched battle to remake British conservatism .

Mexico’s Judiciary Rift: A showdown over a plan by Mexico’s outgoing president to reshape the country’s judiciary is raising fears over the effect on the rule of law and trade with the United States.

An Ancient Irish Game Adapts: For centuries, hurling’s wooden sticks have been made from Ireland’s ash trees. But with a disease destroying forests, the sport is turning to different materials .

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Newsletters

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

- Labor Day sales

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Balance transfer cards

- Cash back cards

- Rewards cards

- Travel cards

- Online checking

- High-yield savings

- Money market

- Home equity loan

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Options pit

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

A 'massive' whale destroyed a sailboat in the middle of the Pacific, leaving 4 friends stranded for 10 hours

Rick Rodriguez and his friends went on a boat journey from the Galapagos to French Polynesia.

About two weeks into the trip, the group found themselves stranded for 10 hours in the middle of the Pacific.

Their sailboat had been struck by a whale and sunk, The Washington Post reported.

One of the first things Rick Rodriguez did after his boat started to sink was text his friend. "Tommy this isn't a joke," he wrote . "We hit a whale and the ship went down."

He really wasn't joking.

Rodriguez and three of his friends were on a three week sailing journey. They had started near the Galapagos Islands and were on their way to French Polynesia. Just shy of two weeks into their journey, however, they found themselves in a lifeboat, floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, The Washington Post reported.

They drifted for 10 hours before a civilian ship finally rescued them, Sail World Cruising, an online sailing publication, reported.

Rodriguez told The Post that him and his friends were eating pizza at about 1:30 p.m. on March 13 when they heard a loud bang. Some 15 minutes later, the boat sank. The friends quickly collected essential supplies like water, food, and documents, and then scrambled into the lifeboat, according to Sail World Cruising.

Rodriguez, who fortunately still had some charge left on a portable wifi device, was able to reach out for help. "Tell as many boats as you can," he told his friend, who was also a sailor. "Battery is dangerously low."

Alana Litz, one of the friends on the sailboat, told the Post she was the first to see what she now believes was a Bryde's whale that was at least 44-feet long — the length of the boat. Bryde's are a species of great whale, similar to blue or humpback whales.

"I saw a massive whale off the port aft side with its side fin up in the air," Litz told the Post.

Rodriguez said he saw it bleeding as it went back into the water.

Fortunately for the stranded crew, there were about two dozen ships sailing in the same direction — part of a yacht race known as World ARC, according to Sail World Cruising.

"There was never really much fear that we were in danger," Rodriguez told The Post. "Everything was in control as much as it could be for a boat sinking."

It's not uncommon for boats and whales to collide, especially with the rise in the amount of cargo and cruise boat traffic. The Los Angeles Times reported that ship strikes have actually been a danger to whales in the Pacific.

"Anywhere you have major shipping routes and whales in the same place, you are going to see collisions," Russell Leaper, an expert with the International Whaling Commission told the Times. "Unfortunately, that's the situation in many places."

The Maritime Executive , a magazine covering maritime issues, reported last week that a sailboat had to be towed to safety in the Strait of Gibraltar after three orcas knocked into it. The magazine reported that orcas have been slamming into boats in the area for years.

A spokeswoman for the International Whaling Commission told the Post that since 2007, there have been 1,200 reports of boats and whales colliding. But according to the US Coast Guard it's rare for collisions to cause significant damage.

Read the original article on Insider

Recommended Stories

Angels' ben joyce comes 0.3 mph short of fastest pitch ever recorded.

The Angels flamethrower struck out the Dodgers' Tommy Edman with some ridiculous heat.

Chicago Sky's Diamond DeShields responds to toxic fan after hard foul on Caitlin Clark

An incident involving Cailtin Clark and the Sky got ugly. Again.

3 smart things to do when your savings account hits $10,000

Saving up $10,000 is a big accomplishment. But how you use that money is also important. Here’s what you can do with $10,000 in savings to improve your financial situation further.

Padres lose crusher to Tigers, giving up grand slam with 2 outs and 2 strikes in 9th inning

The San Diego Padres lost a game to the Detroit Tigers on Thursday in which they were one out and one strike away from winning a game that could be crucial in a playoff race.

Only Amazon Prime members can score these 7 secret deals, starting at just $9

Insider-only bargains include a $20 water flosser (that's 50% off) and $25 off a Samsonite carry-on with a 16,000-person fan club.

Data Dump Wednesday: 10 stats you need to know for Week 1 | Yahoo Fantasy Forecast

Week 1 has arrived and so has our new Wednesday show. Matt Harmon and Sal Vetri debut 'Data Dump Wednesday' by sharing 10 data points you need to know for Week 1 to maximize your fantasy lineups.

Caitlin Clark notches 2nd triple-double, creates 200-assist, 100 3-pointer club in Fever win

Clark is on pace for the most assists ever and the third-most 3-pointers ever.

The US economy may be on 'thinner' ice than investors think

Investors are increasingly confident the US economy will achieve a "soft landing." That may not be the case, according to one strategist.

Carrie Underwood, 'Sunday Night Football' producers lift the lid on this year's 'very different' show open and how the singer took over for Faith Hill, Pink (exclusive)

Carrie Underwood and the NBC Sports team take Yahoo Entertainment behind the scenes of this year's "Sunday Night Football" show open.

Deion Sanders wonders why Travis Hunter and Shedeur Sanders didn't get more Week 1 recognition

Colorado beat FCS school North Dakota State 31-26 in Week 1.

The iOS 18 release date is this month but is your iPhone compatible? Here are the eligible devices and new features

Apple's latest software, including Apple Intelligence features, won't be available for every iPhone user. We'll explain who's getting left out this year.

Mortgage and refinance rates today, September 4, 2024: 30-year fixed still under 6%

These are today's mortgage and refinance rates. Lock in your rate today. The 30-year fixed had been held under 6% for more than a full week. Lock in your rate today.

A Minecraft Movie trailer gives us our first look at Jason Momoa and Jack Black ahead of its 2025 release

It's finally coming to theaters.

Taylor Swift supports Travis Kelce at Chiefs-Ravens game after false breakup contract circulates. They're 'going strong,' says source

What breakup PR contract? Taylor Swift cheers on Travis Kelce at Chiefs home opener as source says they're "solid."

Ford recalls 90,736 vehicles due to engine valve issue

Ford will recall 90,736 vehicles as engine intake valves in the vehicles may break while driving, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

US Open: USA's Emma Navarro rallies from 5-1 second-set deficit, will face Aryna Sabalenka in semifinals

Navarro won the last six games of the match. She was the first of three Americans in quarterfinal play at the US Open on Tuesday.

Yankees have a closer problem, Justin Verlander's quest for 300 wins | Baseball Bar-B-Cast

Jake Mintz & Jordan Shusterman talk about the Yankees' closer problem with Clay Holmes, Shohei Ohtani returning to Anaheim, Ben Joyce throwing 105.5 and Justin Verlander’s quest for 300 career wins.

Researchers discover potentially catastrophic exploit present in AMD chips for decades

Researchers discovered a potentially catastrophic vulnerability in AMD chips that has been there for decades. It’s called a ‘Sinkclose’ flaw.

Gunnar Henderson passes Cal Ripken Jr., Miguel Tejada for most home runs in a season by an Orioles shortstop

Henderson earned his place alongside Orioles royalty on Wednesday.

2024 NASCAR Cup Series playoff preview, predictions: Will there be another first-time champion?

Ten of the 16 drivers in the playoff field are searching for their first Cup Series title. Joey Logano is the only playoff driver with multiple titles.

UK Edition Change

- UK Politics

- News Videos

- Paris 2024 Olympics

- Rugby Union

- Sport Videos

- John Rentoul

- Mary Dejevsky

- Andrew Grice

- Sean O’Grady

- Photography

- Theatre & Dance

- Culture Videos

- Fitness & Wellbeing

- Food & Drink

- Health & Families

- Royal Family

- Electric Vehicles

- Car Insurance Deals

- Lifestyle Videos

- UK Hotel Reviews

- News & Advice

- Simon Calder

- Australia & New Zealand

- South America

- C. America & Caribbean

- Middle East

- Politics Explained

- News Analysis

- Today’s Edition

- Home & Garden

- Broadband deals

- Fashion & Beauty

- Travel & Outdoors

- Sports & Fitness

- Climate 100

- Sustainable Living

- Climate Videos

- Solar Panels

- Behind The Headlines

- On The Ground

- Decomplicated

- You Ask The Questions

- Binge Watch

- Travel Smart

- Watch on your TV

- Crosswords & Puzzles

- Most Commented

- Newsletters

- Ask Me Anything

- Virtual Events

- Wine Offers

- Betting Sites

Thank you for registering

Please refresh the page or navigate to another page on the site to be automatically logged in Please refresh your browser to be logged in

‘Tommy this is not a joke’: Friends send mayday message as boat sinks in Pacific after being hit by whale

Rick rodriguez and crew of three spent 10 hours on a lifeboat and dinghy after collision, article bookmarked.

Find your bookmarks in your Independent Premium section, under my profile

The latest headlines from our reporters across the US sent straight to your inbox each weekday

Your briefing on the latest headlines from across the us, thanks for signing up to the evening headlines email.

A group of friends had to be rescued from the Pacific after their 44ft sailing boat sunk after being struck by a giant whale.

Rick Rodriguez and three friends spent 10 hours on a lifeboat and dinghy after the bizarre reported accident took place on 13 March.

Mr Rodriguez, who is from Florida, was 13 days into a three-week and 3,500-mile crossing of the South Pacific from the Galápagos Islands to French Polynesia when the whale collision took place.

He told The Washington Post that he had been eating vegetarian pizza onboard the boat Raindancer when it ran into the huge whale.

“The second pizza had just come out of the oven, and I was dipping a slice into some ranch dressing,” Mr Rodriguez said in a satellite phone interview with the Post .

“The back half of the boat lifted violently upward and to starboard.”

Crew member Alana Litz added that following the collision she saw “a massive whale off the port aft side with its side fin up in the air.”

And within seconds alarms began sounding warning the group of friends that the boat was taking on water.

Mr Rodriguez says that he issued a mayday call on the boat’s VHF radio and sent out their position in an emergency distress signal. The crew then gathered enough food and water for around a week, as well as emergency equipment before launching the lifeboat and dinghy.

In the rush, they left their passports behind.

Using a phone and satellite hotspot, Mr Rodriquez messaged his friend and sailor Tommy Joyce, who was on the same route but around 180 miles behind them.

“Tommy this is no joke. We hit a whale and the ship went down,” Mr Rodriguez says he messaged his friend.

He also sent a message to his brother Roger urging him to: “Tell mom it’s going to be OK.”

He also asked his sibling to try to contact Mr Joyce on WhatsApp to try to reach him faster.

After turning the wifi hotspot off for two hours to conserve battery life, he finally received a message back from Mr Joyce, saying “We got you bud.”

The crew was eventually rescued hours later.

The Peruvian coast guard had picked up the distress signal and relayed the information to the US Coast Guard station in California.

But, in the end, it was another boat which reached the group first.

The Rolling Stones, captained by sailor Geoff Stone, had heard the mayday call from the Raindancer and coordinated with Mr Joyce and Peruvian officials.

“I feel very lucky, and grateful, that we were rescued so quickly,” added Mr Rodriguez. “We were in the right place at the right time to go down.”

While the crew of the Raindancer should have completed their journey on Wednesday – and had to say goodbye to the Raindancer – the group has no plans of quitting.

Now, they will complete their journey to French Polynesia onboard the Rolling Stones.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

clock This article was published more than 1 year ago

Sailboat crew rescued in Pacific after abandoning ship sunk by whale

Four people aboard the Raindancer were stranded in the Pacific Ocean for 10 hours

His circumstances sounded straight out of “Moby-Dick,” but Rick Rodriguez wasn’t kidding. In his first text messages from the life raft, he said he was in serious trouble.

“Tommy this is no joke,” he typed to his friend and fellow sailor Tommy Joyce. “We hit a whale and the ship went down.”

“Tell as many boats as you can,” Rodriguez also urged. “Battery is dangerously low.”

On March 13, Rodriguez and three friends were 13 days into what was expected to be a three-week crossing from the Galápagos to French Polynesia on his 44-foot sailboat, Raindancer. Rodriguez was on watch, and he and the others were eating a vegetarian pizza for lunch around 1:30 p.m. In an interview with The Washington Post later conducted via satellite phone, Rodriguez said the ship had good winds and was sailing at about 6 knots when he heard a terrific BANG!

“The second pizza had just come out of the oven, and I was dipping a slice into some ranch dressing,” he said. “The back half of the boat lifted violently upward and to starboard.”

The sinking itself took just 15 minutes, Rodriguez said. He and his friends managed to escape onto a life raft and a dinghy. The crew spent just 10 hours adrift, floating about nine miles before a civilian ship plucked them from the Pacific Ocean in a seamless predawn maneuver. A combination of experience, technology and luck contributed to a speedy rescue that separates the Raindancer from similar catastrophes .

“There was never really much fear that we were in danger,” Rodriguez said. “Everything was in control as much as it could be for a boat sinking.”

It wasn’t lost on Rodriguez that the story that inspired Herman Melville happened in the same region. The ship Essex was also heading west from the Galápagos when it was rammed by a sperm whale in 1820, leaving the captain and some crew to endure for roughly three months and to resort to cannibalism before being rescued.

Coast Guard saves overboard cruise passenger in ‘Thanksgiving miracle’

There have been about 1,200 reports of whales and boats colliding since a worldwide database launched in 2007, said Kate Wilson, a spokeswoman for the International Whaling Commission. Collisions that cause significant damage are rare, the U.S. Coast Guard said, noting that the last rescue attributed to damage from a whale was the sinking of a 40-foot J-Boat in 2009 off Baja California, with that crew rescued by Coast Guard helicopter.

Alana Litz was the first to see what she now thinks was a Bryde’s whale as long as the boat. “I saw a massive whale off the port aft side with its side fin up in the air,” Litz said.

Rodriguez looked to see it bleeding from the upper third of its body as it slipped below the water.

Bianca Brateanu was below cooking and got thrown in the collision. She rushed up to the deck while looking to the starboard and saw a whale with a small dorsal fin 30 to 40 feet off that side, leading the group to wonder whether at least two whales were present.

Within five seconds of impact, an alarm went off indicating the bottom of the boat was filling with water, and Rodriguez could see it rushing in from the stern.

Water was already above the floor within minutes. Rodriguez made a mayday call on the VHF radio and set off the Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB). The distress signal was picked up by officials in Peru, who alerted the U.S. Coast Guard District 11 in Alameda, Calif., which is in charge of U.S. vessels in the Pacific.

The crew launched the inflatable life raft, as well as the dinghy, then realized they needed to drop the sails, so that line attaching the life raft didn’t snap as it got dragged behind the still-moving Raindancer.

Rodriguez grabbed his snorkel gear and a tarp and jumped into the water to see whether he could plug the holes, but it was futile. The area near the propeller shaft was badly punched in, he said.

Meanwhile, the others had gathered safety equipment, emergency gear and food. In addition to bottled water, they filled “water bottles, tea kettles and pots” before the salt water rose above the sink, Rodriguez said.

“There was no emotion,” Rodriguez recalled. “While we were getting things done, we all had that feeling, ‘I can’t believe this is happening,’ but it didn’t keep us from doing what we needed to do and prepare ourselves to abandon ship.”

Rodriguez and Simon Fischer handed the items down to the women in the dinghy, but in the turmoil, they left a bag with their passports behind. They stepped into the water themselves just as the deck went under.

Rodriguez swam to the life raft, climbed in and looked back to see the last 10 feet of the mast sinking “at an unbelievable speed,” he said. As the Raindancer slipped away, he pulled a Leatherman from his pocket and cut the line that tethered the life raft to the boat after Litz noticed it was being pulled taut.

They escaped with enough water for about a week and with a device for catching rain, Rodriguez said. They had roughly three weeks worth of food, and a fishing pole.

The Raindancer “was well-equipped with safety equipment and multiple communication devices and had a trained crew to handle this open-ocean emergency until a rescue vessel arrived,” said Douglas Samp, U.S. Coast Guard Pacific area search and rescue program manager. He cautioned that new technology should not replace the use of an EPIRB, which has its own batteries.

Indeed, the one issue the crew faced was battery power. Their Iridium Go, a satellite WiFi hotspot, was charged to only 32 percent (dropping to 18 percent before the rescue). The phone that pairs with it was at 40 percent, and the external power bank was at 25 percent.

Rodriguez sent his first message to Joyce, who was sailing a boat on the same route about 180 miles behind. His second was to his brother, Roger, in Miami. He repeated most of what he had messaged to Joyce, adding: “Tell mom it’s going to be okay.”

Rodriguez’s confidence was earned. A 31-year-old from Tavernier, Fla., he had spent about 10 years working as a professional yacht captain, mate and engineer. He bought the Raindancer in 2021 and lived on her, putting sweat equity into getting the boat, built in 1976, ready for his dream trip.

Both he and Brateanu, 25, from Newcastle, England, have mariner survival training. Litz, 32, from Comox, British Columbia, was formerly a firefighter in the Canadian military. Fischer, 25, of Marsberg, Germany, had the least experience, but “is a very levelheaded guy,” Rodriguez said.

Rodriguez gave detailed information on their location and asked his brother to send a message via WhatsApp to Joyce, who has a Starlink internet connection that he checks more frequently than his Iridium Go. Because of his low battery, he told his brother that he was turning the unit off and would check it in two hours.

Rodriguez also activated a Globalstar SPOT tracker, which transmitted the position of the life raft every few minutes, and he broadcast a mayday call every hour using his VHF radio.

When he turned the Iridium Go back on at the scheduled time, there was a reply from Joyce: “We got you bud.”

As luck would have it, the Raindancer was sailing the same route as about two dozen boats participating in a round-the-world yachting rally called the World ARC. BoatWatch, a network of amateur radio operators that searches for people lost at sea, was also notified. And the urgent broadcast issued by the Coast Guard was answered by a commercial ship, Dong-A Maia, which said it was 90 miles to the south of Raindancer and was changing course.

“We have a bunch of boats coming. We got you brother,” Joyce typed.

“Can’t wait to see you guys,” Rodriguez replied.

Joyce told Rodriguez that the closest boat was “one day maximum.”

In fact, the closest boat was a 45-foot catamaran not in the rally. The Rolling Stones was only about 35 miles away. The captain, Geoff Stone, 42, of Muskego, Wis., had the mayday relayed to him by a friend sailing about 500 miles away. He communicated with Joyce via WhatsApp and with the Peruvian coast guard using a satellite phone to say they were heading to the last known coordinates.

In the nine hours it took to reach the life raft, Stone told The Post, he and the other three men on his boat were apprehensive about how the rescue was going to work.

“The seas weren’t terrible, but we’ve never done a search and rescue,” he said. He wasn’t sure whether they would be able to find the life raft without traveling back and forth.

He was surprised when Fischer spotted the Rolling Stones’ lights from about five miles away and made contact on the VHF radio.

Once it got closer, Rodriguez set off a parachute flare, then activated a personal beacon that transmits both GPS location and AIS (Automatic Identification System) to assist in the approach. Although the 820-foot Dong-A Maia, a Panamanian-flagged tanker, was standing by, it made more sense to be rescued by the smaller ship.

To board the Rolling Stones, the crew from the Raindancer transferred to the dinghy with a few essentials, then detached the life raft so it wouldn’t get caught in the boat’s propeller.

“We were 30 or 40 feet away when we started to make out each other’s figures. There was dead silence,” Rodriguez said. “They were curious what kind of emotional state we were in. We were curious who they were.”

“I yelled out howdy” to break the ice, he explained.

One by one, they jumped onto the transom. “All of a sudden, us four were sitting in this new boat with four strangers,” Rodriguez said.

The hungry sailors were given fresh bread, then were offered showers. The Rolling Stones crew gave their guests toothbrushes, deodorant and clothes. None even had shoes.

Rodriguez said he had tried not to think about losing his boat while the crisis was at hand. But, the first morning he woke up on Rolling Stones, it hit him. Not only had he lost his home and belongings, but he also felt as if he’d lost “a good friend.”

“I’ve worked so hard to be here, and have been dreaming of making landfall at the Bay of Virgins in the Marquesas on my own boat for about 10 years. And 1,000 nautical miles short, my boat sinks,” Rodriguez said.

The Rolling Stones is expected to arrive in French Polynesia on Wednesday, and Rodriguez is glad that he’s onboard.

“I feel very lucky and grateful that we were rescued so quickly,” he said. “We were in the right place at the right time to go down.”

Karen Schwartz is a writer based in Fort Collins, Colo. Follow her on Twitter @WanderWomanIsMe .

A previous version of this article misstated the size of the J-boat that sank in 2009. It was 40 feet.

More travel news

How we travel now: More people are taking booze-free trips — and airlines and hotels are taking note. Some couples are ditching the traditional honeymoon for a “buddymoon” with their pals. Interested? Here are the best tools for making a group trip work.

Bad behavior: Entitled tourists are running amok, defacing the Colosseum , getting rowdy in Bali and messing with wild animals in national parks. Some destinations are fighting back with public awareness campaigns — or just by telling out-of-control visitors to stay away .

Safety concerns: A door blew off an Alaska Airlines Boeing 737 Max 9 jet, leaving passengers traumatized — but without serious injuries. The ordeal led to widespread flight cancellations after the jet was grounded, and some travelers have taken steps to avoid the plane in the future. The incident has also sparked a fresh discussion about whether it’s safe to fly with a baby on your lap .

A 'massive' whale destroyed a sailboat in the middle of the Pacific, leaving 4 friends stranded for 10 hours

- Rick Rodriguez and his friends went on a boat journey from the Galapagos to French Polynesia.

- About two weeks into the trip, the group found themselves stranded for 10 hours in the middle of the Pacific.

- Their sailboat had been struck by a whale and sunk, The Washington Post reported.

One of the first things Rick Rodriguez did after his boat started to sink was text his friend. "Tommy this isn't a joke," he wrote . "We hit a whale and the ship went down."

He really wasn't joking.

Rodriguez and three of his friends were on a three week sailing journey. They had started near the Galapagos Islands and were on their way to French Polynesia. Just shy of two weeks into their journey, however, they found themselves in a lifeboat, floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, The Washington Post reported.

They drifted for 10 hours before a civilian ship finally rescued them, Sail World Cruising, an online sailing publication, reported.

Rodriguez told The Post that him and his friends were eating pizza at about 1:30 p.m. on March 13 when they heard a loud bang. Some 15 minutes later, the boat sank. The friends quickly collected essential supplies like water, food, and documents, and then scrambled into the lifeboat, according to Sail World Cruising.

Rodriguez, who fortunately still had some charge left on a portable wifi device, was able to reach out for help. "Tell as many boats as you can," he told his friend, who was also a sailor. "Battery is dangerously low."

Alana Litz, one of the friends on the sailboat, told the Post she was the first to see what she now believes was a Bryde's whale that was at least 44-feet long — the length of the boat. Bryde's are a species of great whale, similar to blue or humpback whales.

"I saw a massive whale off the port aft side with its side fin up in the air," Litz told the Post.

Rodriguez said he saw it bleeding as it went back into the water.

Fortunately for the stranded crew, there were about two dozen ships sailing in the same direction — part of a yacht race known as World ARC, according to Sail World Cruising.

Related stories

"There was never really much fear that we were in danger," Rodriguez told The Post. "Everything was in control as much as it could be for a boat sinking."

It's not uncommon for boats and whales to collide, especially with the rise in the amount of cargo and cruise boat traffic. The Los Angeles Times reported that ship strikes have actually been a danger to whales in the Pacific.

"Anywhere you have major shipping routes and whales in the same place, you are going to see collisions," Russell Leaper, an expert with the International Whaling Commission told the Times. "Unfortunately, that's the situation in many places."

The Maritime Executive , a magazine covering maritime issues, reported last week that a sailboat had to be towed to safety in the Strait of Gibraltar after three orcas knocked into it. The magazine reported that orcas have been slamming into boats in the area for years.

A spokeswoman for the International Whaling Commission told the Post that since 2007, there have been 1,200 reports of boats and whales colliding. But according to the US Coast Guard it's rare for collisions to cause significant damage.

- Main content

Pacific Sailboat Crew Rescued After Abandoning Ship Sunk by Whale Collision

On March 13th, a party of companions had already been sailing for 13 days from the Galápagos to French Polynesia on the Raindancer, a 44-foot sailboat. Suddenly, they heard a loud noise, and Rick Rodriguez, the owner of the boat, was in the middle of enjoying some pizza when he felt the stern of the boat lift up and shift to starboard. It became apparent that they had struck a whale. The crew quickly inflated their lifeaft, and loaded their dinghy with essential supplies such as food, water, and communication equipment, and within 15 minutes, the Raindancer sunk beneath the waves.

After the collision with the whale and the Raindancer began to sink, Rick Rodriguez promptly sent out a mayday distress signal on the VHF radio. He and his companions then proceeded to evacuate onto the lifeboat and dinghy, taking essential supplies with them. In a report by The Washington Post, Rodriguez recounted that he and his friends felt a sense of disbelief and shock that this was happening, but they remained calm and focused on gathering what they needed to prepare for abandoning the ship. Despite the surreal situation, they managed to act efficiently and without much emotional turmoil, as Rodriguez stated: "While we were getting things done, we all had that feeling, 'I can't believe this is happening,' but it didn't keep us from doing what we needed to do and prepare ourselves to abandon ship."

Following the evacuation, the crew of the Raindancer spent 10 hours adrift before being rescued by the civilian boat Rolling Stone. The rescue was described as seamless and efficient. The Raindancer was equipped with various communication devices and emergency equipment, and its crew was trained to handle worst-case scenarios. Despite these measures, collisions between whales and boats have been on the rise since 2007, with approximately 1,200 such incidents recorded to date. Alana Litz, one of the individuals on board the Raindancer, believes that the whale they struck was a Bryde's whale, and she and her companions observed the animal bleeding as it swam away.

Rodriguez expressed his gratitude for the swift rescue, stating: "I feel very lucky and grateful that we were rescued so quickly. We were in the right place at the right time to go down." Despite the unfortunate event, he and his companions were grateful to have made it out alive and credited their preparedness and training for helping them handle the situation as best they could.

For the full story visit The Washington Post .

Want to Stay In the Loop?

Stay up to date with the latest articles, news and all things boating with a FREE subscription to Marinalife Magazine!

latest in US News

Trump appears at Manhattan federal court as lawyers seek to...

Newlyweds charged with murdering their groomsman on their wedding...

Hunter Biden reveals why he stunningly pleaded guilty in $1.4M...

New audio reveals how Colt Gray's father reacted to police when...

Pets strut their stuff at NYFW charity show: 'They have very big...

Ga. shooting suspect warned he will face life in prison, dad sobs...

Biden trashes Trump in Wisconsin visit, comparing himself to FDR,...

Human remains believed to be hundreds of years old found on...

4 pals spend 10 hours adrift in pacific ocean after whale sinks their boat.

A giant whale plunged a group of sailors into a scene straight out of “Moby-Dick” when it sank their boat in the Pacific Ocean — where they waited in a life raft for 10 hours before they were rescued.

Rick Rodriguez, 31, of Tavernier, Florida, and three pals set off from the Galápagos Islands on his 44-foot sailboat Raindancer for a three-week, 3,500-mile journey to French Polynesia, the Washington Post reported .

But on March 13, less than two weeks into the trip, things went horribly wrong.

Rodriguez, a native of Newcastle, England, and the others were enjoying a lunch of vegetarian pizza when they heard a loud noise about 1:30 p.m.

“The second pizza had just come out of the oven, and I was dipping a slice into some ranch dressing,” Rodriguez told the paper over a satellite phone. “The back half of the boat lifted violently upward and to starboard.”

The group quickly gathered essential supplies, including water and food – then scrambled into a life raft and dinghy before the boat sank in about 15 minutes.

Rodriguez made a mayday and set off the Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, whose signal was picked up by officials in Peru, who alerted the US Coast Guard in California.

Fortunately, the group also had an Iridium Go satellite WiFi hotspot and a phone, though they were only partially charged and an external battery pack was only at 25 percent, the Washington Post said.

“Tommy this is no joke,” Rodriguez messaged his friend Tommy Joyce, who was sailing the same route but was some 180 miles behind.

“We hit a whale and the ship went down. Tell as many boats as you can. Battery is dangerously low,” he typed.

Rodriguez sent a similar message to his brother Roger in Miami.

“Tell mom it’s going to be OK,” he added confidently.

When he checked the Iridium Go later, he saw Joyce’s reassuring message: “We got you bud. We have a bunch of boats coming.”

Rodriguez replied: “Can’t wait to see you guys.”

The Raindancer happened to be sailing the same route as about two dozen other vessels taking part in a yachting rally called the World ARC.

An alert sent by the Coast Guard was picked up by the Dong-A Maia, a Panamanian-flagged tanker sailing 90 miles to the south of Raindancer. It quickly changed course.

The sailors, who were thrown by the large impact, all noticed that a whale had rammed their boat.

“I saw a massive whale off the port aft side with its side fin up in the air,” Alana Litz, 32, a former firefighter in the Canadian military, told the news outlet.

She said she believes it was a Bryde’s whale that was about as long as the vessel.

Rodriguez noticed that it was bleeding as it slipped below the surface.

Bianca Brateanu, a 25-year-old from Newcastle, had been cooking below at the time of the collision and rushed up to see a whale at starboard, leading the group to wonder if at least two whales were present.

Also onboard was Simon Fischer, 25, of Marsberg, Germany, who had the least experience but “is a very levelheaded guy,” Rodriguez told the Washington Post.

The friends abandoned the Raindancer with enough water for about a week and roughly three weeks’ worth of food. They also had a fishing pole and a device for collecting rain.

But the rescue came after about 10 hours.

The Rolling Stones, a 45-foot catamaran captained by Wisconsin native Geoff Stone, was only about 35 miles away and he received a relayed mayday call.

Stone communicated with Joyce and with Peruvian authorities via WhatsApp to say he was heading to the last known location, which he reached a few hours later.

“The seas weren’t terrible but we’ve never done a search and rescue,” he told the Washington Post, adding that Fischer spotted his lights from about five miles away.

Rodriguez set off a flare and activated a beacon to assist in the final approach.

Although the Dong-A Maia also was nearby, the friends decided to board The Rolling Stones.

“We were 30 or 40 feet away when we started to make out each other’s figures. There was dead silence,” Rodriguez said.

“They were curious what kind of emotional state we were in. We were curious who they were. I yelled out ‘howdy” to break the ice,” he told the paper.

“All of a sudden us four were sitting in this new boat with four strangers,” Rodriguez added.

He told the outlet that “there was never really much fear that we were in danger. Everything was in control as much as it could be for a boat sinking.”

It also wasn’t lost on him that the story that inspired Herman Melville to write the 1851 novel happened in the same area.

The ship Essex also was sailing west from the Galápagos in 1820 when it was rammed by a sperm whale, leaving the captain and some crew members to spend about three months adrift as they resorted to cannibalism before being rescued.

Fortunately, Rodriguez and his friends didn’t have to face such an unsavory outcome.

“I feel very lucky, and grateful, that we were rescued so quickly,” he told the paper. “We were in the right place at the right time to go down.”

The Rolling Stones was expected to arrive in French Polynesia on Wednesday.

Advertisement

- Advertising

- Find the Magazine

- Good Jibes Podcast

- Boat In Dining

- Sailboat Charters

- Business News

- Working Waterfront

- Youth Sailing

- General Sailing

- Current News

Sailboat Sinks After Collision with Whale in South Pacific

It was like an excerpt from a Herman Melville book: “Vessel has sunk. They were hit by a whale.” Those words were shared across social media channels on Monday as sailors networked to send aid to the stricken crew of Raindancer (we believe a Kelly Peterson 44). Also in the shared post were the words “Not a drill.”

The post was created by Tommy Joyce, a member of Facebook’s “Starlink on Boats” group. Tommy is a friend of Raindancer ‘s owner, Rick Rodriguez, and was alerting the boating community to the situation. “They hit [have] a liferaft and have Iridium on board.”

They were almost in the middle of the Pacific with no other boats in sight. But a successful rescue was coordinated through the power of social media and modern communications, including new kid on the block Starlink.

We contacted Paul Tetlow, managing director of World Cruising Club, who is operating as “rally control” for the World ARC cruising rally. He told us that upon learning of Raindancer ‘s demise and the position of the crew, he contacted the Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) who then assigned MRCC Peru to coordinate the rescue. But before the official rescue had been executed, a network of communications had quickly arisen, much of it via Starlink, and around eight ARC vessels diverted their course to assist Raindancer ‘s crew. Along the way, ARC participants aboard S/V Far were able to keep up the communications with the lifeboat using Iridium and Starlink.

Here’s what we understand about the incident. Raindancer was “13 days into a 20-22-day, 3000nm ocean crossing,” Vinny Mattiola wrote on Facebook, when the vessel was struck by a whale, which “damaged the skeg and prop strut, and the boat was completely underwater in <15mins, forcing all four crew to abandon into the life raft.” They were approximately midway between the Galápagos and French Polynesia.

Fortunately the crew were cool-headed and quickly loaded the raft with water, provisions, and emergency communications and survival equipment, and secured Raindancer ‘s dinghy alongside. Mattiola believes the crew’s Iridium GO! device, which they carried along with their SPOT tracker, was instrumental in their rescue.

Within 10 hours of Raindancer going under, her four crew were rescued and taken aboard the sailing vessel Rolling Stones . “A very quick response time,” Tetlow said. “A good achievement.” Tetlow believes Starlink adds “another layer of ability to solve problems quickly,” and that the Starlink communications probably did add to the expedience of the rescue.

According to reports, the boat’s EPIRB hadn’t worked as intended, but the US Coast Guard later confirmed that it had indeed worked, the crew just “didn’t know it.” When we learned of Raindancer ‘s distress, we contacted Douglas Samp, USCG Search and Rescue Program Manager for the Pacific, and Kevin Cooper, Search and Rescue Program Manager, Hawaii, who were already coordinating rescue with MRCC Peru. Samp later explained, “There is no country in the world that has SAR resources able to respond 2400 miles offshore, so we rely upon other vessels to assist. RCC Alameda assisted MRCC Peru with a satellite broadcast to GMDSS-equipped vessels and diverted an AMVER (Automated Mutual-Assistance Vessel Rescue) vessel, M/V DONG-A MAIA , to assist, but the Rolling Stones got there first. BZ to your sailing community for rescuing your own.”

Mattiola concluded his post: “All crew are safe and even sent me a voice message thanking everyone involved.”

We hope to share more about this story in the next issue of Latitude 38 .

*Editor’s note: Upon learning the full details of this story, the headline was changed from Sailboat Sinks After Being Rammed By Whale in South Pacific to Sailboat Sinks After Collision with Whale in South Pacific.

29 Comments

Seems the whales are trying to get even.

So glad everybody is safe! Kudos to the rescue team

It would be an interesting study to determine if there’s a correlation between whale strikes and the color of bottom paint.

A bit over the top on the title. “Rammed”? Really. Rammed implies the whale was trying to damage the boat. Do we even know if the boat hit the whale rather than the whale hitting the boat?

Exactly what I was thinking

The boat hit the whale. To say the opposite is just incorrect. Bad reporting.

The whale struck the boat. Scientists believe they associate boats in that area with whaling. Same thing happened around that area about a year ago.

This may have to go to litigation. Some say the whale was double-parked with one taillight out when the Pacific highway was busy with the World ARC Rally, PPJ Rally and other westward-bound cruisers.

It is roughly where the whaling ship Essex, which sailed from Nantucket, was sunk in November of 1820 when it was rammed/attacked by a vengeful sperm whale. The story laid the foundation for Herman Melville’s book ‘Moby Dick.’ The actual story of the sinking of the Essex is told in a great book by Nathaniel Philbrick in his book, “The Heart of the Sea.” Once again the whale didn’t get to tell their side of the story but it certainly might have included the fact that the whaling ship was out there trying to kill it. In 1820 whaling ships were starting to hunt for whales to the west of the Galapagos after major populations of whales in the Atlantic had been depleted. Moby Dick and The Heart of the Sea are both worth a read. Have a look in the Latitude 38 bookstore: https://bookshop.org/shop/latitude38

Hi John, Even if the whale did hit the boat (which is a really hard thing to determine at sea), using the word ‘rammed’ implies intent. And, except for the orca problems off of Gibraltar, and Moby Dick, I don’t think we can attribute intention to the whale. It just sounds sensational.

As for whales associating boats in that area with whaling… that’s a hard one to believe. Many thousands of boats have sailed safely through that area since whaling was banned.

Cheers, Bruce

Oh, and by the way, I thought the movie THE HEART OF THE SEA was excellent. One of the few sailing films that treated the sailing parts realistically. They were never turning the wheel to port and the ship would go starboard!

I was also thinking ? the same thing. Striking a whale that was “perhaps” (I don’t know) resting or sleeping, is completely different than rammed. That infers they were attacked.

As an aside. In their posts the crew have used the terminology that their boat hit the whale. Not that the whale hit them, or attacked them. This is verbiage used by other sailors.

It’s always heartwarming to hear that all survived. And yes, let’s not Moby Dick the whale, before we hear the whole story.

They said the whale hit the”skeg and prop strut” like they didn’t hit the whale, read the !@#$%^& message, I’m curious as to what species it was; the Galapagos islands area has a history of Orcas attacks.

The book “Survive the Savage Sea” by Dougal Robertson comes to mind. Similar situation and location aboard 43ft schooner “Lucette” in the year 1972.

I think it was reported other way round, the boat hit the whale who was sleeping on surface and crew didnt spot him.

Hope the whale is unhurt.

I hope so also??as stated above they maybe trying to get even,if so they got a long way to go

Regarding the incident and life-saving equipment referenced , can anyone remark about range instruments (existing or future planned) that can monitor/detect massive underwater objects (e.g. our beloved whales) ? I’ve crossed the seas, racing and deliveries; and such an event never occurred to me. Thanks

Everyone is so concerned about who hit who but do we know what kind of whale? Is it ok? Was it properly called in to authorities to try and see if it’s a tagged whale they might be able to check up on?

Good point! The collision must have done a number on the whale too.

One crew member saw the whale immediately after the collision, and believed it to be a Bryde’s whale. This would make sense as the species is highly sensitive to disturbances. She reported that the whale appeared to be bleeding. KP44’s are strong hulls and the area around the skeg/rudder post was caved in, which caused the vessel to sink in 15 minutes.

A sad business all the way around .

CLICKBAIT !!! The whale didn’t “ram” the boat… FFS !!

Sounds to me like the whale was surfacing from a dive and hit the propeller, which in turn, caused the damage to the fibergass where the shaft exited the hull. Using the word rammed is for publicity, and distorts the facts.

For those who wish to help the Captain and the crew in these tragic events https://gofund.me/c576a554

No insurance?

Shocking headline to catch readers but untrue. Read the skippers report- the boat collided with the whale which was seen swimming off in a trail of blood.

There is also the Theory that “Herd Bull” whales will protect their group by challenging intruders, just as large mammals on land will do.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Notify me via e-mail if anyone answers my comment.

Sailing for Your Ears Good Jibes #82: Andy Schwenk on Surviving a Scare Andy is a longtime Express 37 sailor, Bay Area marine surveyor, and Richmond Yacht Club port captain who has truly seen it all.

Sponsored Post New Year’s Special at San Francisco BoatWorks New Year's Special! 50% haul & launch with bottom paint. Call (415) 626-3275 for more information or visit www.sfboatworks.com.

Colleges Winning in Keelboats University of Hawaii Wins Port of Los Angeles Harbor Cup Collegiate keelboat racing is alive and well with the Port of Los Angeles-sponsored Port of L.A. Harbor Cup.

More Than A Vacation Chartered Bavaria 50 Used in Bombing of Nord Stream Pipeline? A chartered Bavaria 50 is alleged to have taken part in planting the explosives that ruptured the Nord Stream pipeline in the Baltic Sea.

Sponsored Post Need Fast, Reliable Internet On Your Boat? Our high-speed fixed wireless base stations and private Bay Area fiber ring offer the reliability, redundancy, and resiliency needed to keep you online, no matter where you call home!

Four Sailors Rescued from Liferaft after SV Raindancer Hit by Whale in South Pacific

May 23, 2023 | Resolved , Safety at Sea , Stories , Top Articles

Key Communications in An Offshore Rescue

By ann hoffner contributing editor ocean navigator magazine may/june 2023, short tacks, on march 13, on a south pacific crossing midway between galapagos and the marquesas, s/v raindancer with four people on board sank after an encounter with a whale. it was lunchtime and they had been in the cockpit eating pizza. in 15 minutes the boat, a peterson 44, had slipped beneath the surface and the crew were surveying a sunny sea from the slim shelter of a liferaft and inflatable dinghy tied together., before abandoning ship the crew gathered supplies and the captain, rick rodriguez, acti- vated an epirb and sent out a mayday on vhf., once in the liferaft they activated a globalstar spot tracker, started regular mayday signals via handheld vhf, and turned on an iridiumgo and cell phone (creating a satellite service wifi hot-spot) to mes- sage rick’s brother on land, and a friend on s/v southern cross sailing 160 nm behind., after sending brief messages they turned the devices off. the liferaft carried several weeks’ worth of vital provisions but their emergency signaling devices had precious little bat- tery power. two hours later on start-up there were messages. one, from tommy joyce on southern cross , said, “we got you bud.”, what the raindancer crew couldn’t know was that from the time the epirb went off, and rick’s text messages were received, two streams of rescue communications were started and they flowed and inter- twined throughout the nine hours it took for a rescue boat to find them., initial reports of the rescue were confused and shifting. in the new age of commu- nications this shouldn’t be a surprise; much was said on social media, especially on the facebook page of boatwatch, an organization that main- tains a worldwide network of resources to aid the search for missing or overdue mariners and relay urgent messages. according to eddie tuttle, boatwatch was alerted by don preuss, a cruiser in panama, that mayday messages were showing up on social media and their own facebook page became a central message platform. the use of social media allows information to be widely disseminated but also leads to a cacophony of voices, not all directly involved but all eager to participate. initially it was reported that raindancer’s epirb did not function, but that proved to be false, and the signal set off an official sar chain of command that began in peru and was rerouted through rescue coordination center (rcc) alameda in california, where the us coast guard fielded phone calls and coordinated via automated mutual-assistance vessel res- cue (amver) to divert a commercial ship to the liferaft., rick’s text messages set off another effort, one that ulti- mately led to the raindancer crew’s successful rescue., an unusual aspect of this situation was the presence of a couple dozen boats in the 2023 world arc, an international circumnavigation rally, coming up behind raindancer . on receiving reports “by multiple means” of the sinking, rally control put out a fleet mes- sage to rally crews. the world arc ssb radio duty control- ler, chris parker on mistral of portsmouth, also relayed the distress message , and ten arc boats close to raindancer ’s lat- est coordinates changed course along with two non-arc boats, including s/v rolling stones , which turned out to be closest, only 35 nm away., tommy joyce did not receive the original message from rick because he doesn’t check iridium much, but he did get the message from rick’s brother which came through whatsapp via tommy’s star- link. (fb) “at that moment, i set up multiple chats, posts and other comms.” ninety per- cent of the tools tommy used required fast internet access, which starlink provided. he was able to communicate with both rolling stones and with the sar assets. ultimately rolling stones and a panamani- an-flagged tanker both arrived at the scene, but it was easier to board the sailboat and rain- dancer’s crew was able to turn on a personal locator beacon (plb) and shoot off a para- chute flare to guide them in., both efforts depended on satellite communications, and were run more or less in parallel. a question raised on boatwatch’s facebook page was whether/how in future the land-based sar scenario could be altered to include recreational boats, which are not now included. amver is a world-wide voluntary ship reporting system operated by the united states coast guard that gives the sar authorities information on and commu- nications access to vessels near a reported disaster. only mer- chant vessels more than 1,000 gross tons on a voyage of 24 hours or longer are eligible to enroll in amver, but sar coordinator at rcc in ala- meda kris robertson posted on boatwatch fb that it was helpful to have had phone numbers for all sailing vessels that were involved in the rescue or relaying information. “most of the time communications is the hardest part of any res- cue coordination…question for the group, is there a place where you all keep underway phone numbers for sailing vessels”, eddie and glenn tuttle and boatwatch along with tommy joyce were instrumental again a few days later when a crew member on board a world arc boat s/v cepa had a serious stroke. cepa was 6-7 days’ sail out of the marquesas without enough fuel to motor flat out. the captain was able to email rescue coordinators in germany, world arc rally control, and a medical support for german-flagged vessels. jrcc papeete was contacted, rcc alameda released safetynet and safetycast group emergency messages to ships over iridium and inmarsat, and the captain also sent a distress call to the chat group of the arc fleet. tommy joyce again acted as a mobile command center. the arc boats were able to scan the area around cepa’s position using ais and assist in locating nearby boats that could help. s/v pec divert- ed from the rally to provide medicine and ultimately their captain went into the rescue effort as doctor. even with this help, there was still the issue of time. a motor yacht, paladin, located through ais, did not respond to initial attempts to communicate. in a stroke of fortune for all involved, the email list used to forward the distress call to the rally fleet included a weather routing company that recognized the yacht as a previous customer and was able to contact the yacht’s owner, who then con- tacted the captain, initiating a successful evacuation of the crew member complete with delivery of enough fuel to increase paladin’s speed and allow them to divert to nuku hiva., “two back-to-back amazing rescues,” said eddie., it’s hard to imagine that all the activity in raindancer ’s rescue only lasted about 10 hours, yet photos of the four people sitting on s/v rolling stones showed up on facebook the day after the sinking., for all the hoopla, especially given the unusual circumstance of the rally being in the vicinity, it’s important to remember that rescue options are usually scant, potential rescuers scattered far and wide, and those of us out on the ocean need to be take responsibility for our adventurous tendencies., peter nielsen posted on the boat watch facebook page that when he crewed on a cat in the pacific in 2020 that was hit by a whale, the coast guard picked up the epirb signal, emailed the boat via iridiumgo and initiated voice contact, leading to rescue nine hours later by a chinese fishing boat., eddie says besides online they also posted an emergency message for the maritime mobile service network (mmsn.org) which is read by ham radio operators on ham radio frequency 14.300, a world wide network of ham radio operators communicating with vessels at sea. i spent 10 years in the pacific on a peterson 44, and often this radio net was the only live link my husband and i had to land., it takes an ocean., contributing editor ann hoffner and husband tom bailey cruised on their peterson 44, oddly enough. she’s now based in sorrento, maine., noonsite.com – re ocean navigator article”key communications in an offshore rescue” by ann hoffer, the role of technology in rescues, this article for ocean navigator by ann hoffer, key communications in an offshore rescue (page 18), demonstrates how technology is changing the way rescues at sea work. it’s a detailed account of two yacht rescues in the south pacific in march 2023., eddie tuttle of boatwatch , who was involved in the rescue, told noonsite; “i think this is one of the most amazing stories ever of communication, captain and crew safety skill and the maritime community coming together. when tommy joyce commented on boat watch facebook that he had set up a mobile command post in the vast pacific ocean, i drew a sigh of relief and amazement at this cruiser stepping up in such a profound and diligent way., he also did a great job along with raindancer’s shore side contact vinny matiola, of coordinating the numerous people trying to help. and then there is the boat, sv rolling stones, that diverted and took 4 more crew on in the middle of nowhere. i still wonder how the provisions went.to top off the raindancer episode, soon thereafter tommy joyce helped handle the medical emergency and dramatic rescue on sv cepa in the middle of nowhere, chris parker, marine weather center, who has helped boatwatch and various coast guards and relayed distressed messages for countless boats, also assisted as the worldarc ssb radio controller., ann hoffner sums up her article by saying, “it takes an ocean”. so true. i encourage cruisers to read the article (page 18) “., the rescue coordination centers worldwide and other resources can be found at https://boatwatch.org/resources/.

This is the Captain, Rick Rodriquez, of Raindancer’s first account posted on Facebook.