Sailboat Hulls: Steel Vs Fiberglass

For decades, sailors and boat owners have been having hotly contested debates about the merits of steel hulls vs fiberglass hulls in sailboats.

The major benefits of boats with steel hulls are that they are very strong, durable, and can be repaired easily. On the other hand, a fiberglass hull offers your boat a smooth and sleek look that is very pleasing. They are also lighter, faster, and require less maintenance than steel boats.

Whether you are building your own sailboat or thinking of buying one, getting the right material for the hull is of paramount importance. Your choice of material should depend on consideration of multiple factors, including its durability, stability, maintenance, repairs, weight, comfort, safety, and cost.

We have a team of sailing experts who have spent decades on the water and have set sail on boats built of all types of materials available. So who better to walk you through the pros and cons of steel and fiberglass hulls?

Table of contents

Steel Hull vs Fiberglass Hull: Top 10 Factors to Consider

Let us take a look at some of the major factors that can help you determine whether a boat with a steel hull or fiberglass hull will be a better choice for you.

Sailboats with steel hulls are much more durable and stronger than those with fiberglass hulls. Steel sailboats have a more rigid structure and are quite robust so they can better understand grazes, rubs, and bumps when out in the open water.

In case of impact, a steel hull will bend and may become dented; however, a fiberglass hull has a higher possibility of breaking. That’s because steel is more ductile and can withstand strong blows without losing its toughness.

Fiberglass is a lighter material than steel, making fiberglass boats lighter. Many people prefer this quality since it means that the boat will travel faster on water and will require less power and wind energy to move than a boat with a steel hull. This means lower fuel consumption and more savings. However, a fiberglass boat will be more prone to be buffeted by the winds since it is lighter.

Anti-Corrosion Properties

The sailboat manufacturing industry now uses state-of-the-art technology and makes use of the best quality materials to make the hull. Steel corrodes when exposed to the atmosphere. However, if the right alloy is used for making the hull, it will resist saltwater corrosion, without even needing special paint.

Steel boats also experience electrolytic or galvanic corrosion, but they can be avoided with the use of insulated electrical connections and sacrificial anodes.

Fiberglass does not corrode. However, it can still suffer from osmosis if the fiberglass had air bubbles at the time of lamination. This can cause water to collect in the void, forming blisters that can weaken the hull. Fiberglass may also become damaged from ultraviolet radiation.

Since steel boats are heavier than fiberglass boats, it means they are more stable on the sea, particularly if you experience choppy waters. A fiberglass boat, on the other hand, is lighter, and hence sailors may experience a rougher journey on choppy waters.

In addition, due to its extra weight, steel boats drift slower and more predictably, which is particularly useful for anglers.

Maintenance

Many steel boats require greater maintenance since they are more prone to corrosion. Galvanic corrosion can occur when two different metals are placed together. Hence, it is important that you ensure that high-quality materials, joints, and screws are used on the hull. It is important to rinse the hull with fresh water once it is out of the sea.

Fiberglass boat hulls do not have welds and rivets and you do not need to worry about the hull rusting. However, it can experience osmosis issues, which can cause serious problems if they are not treated in time.

Both fiberglass and steel boats require antifouling application to prevent barnacles, algae, and other sea organisms from sticking to the hull. However, antifouling can be more expensive for steel boats.

It is easy to repair small dents in steel boats. However, if the damage is extensive, it can be more complicated and costly to repair or replace large sections of steel hulls. Welding a boat hull is a specialized job that requires trained professionals.

It is easier to repair a broken fiberglass hull, but it may never have the same strength and durability as the original hull since the structural tension will not be equal at all points.

Fiberglass boats are made of petroleum-based products that are flammable. Hence, in case of a fire, they will burn easily and quickly. A steel boat is much safer since it cannot burn. In addition, a significant impact from an unidentified floating object can result in a breach in a fiberglass hull easily and open up a waterway into the boat that can cause it to sink. Steel, on the other hand, can withstand larger impacts without compromising the integrity of the boat.

Steel boats operate much louder than fiberglass boats, especially in turbulent seas at high speed. Steel is also a good conductor of heat and if it is not well-insulated during construction, it can become uncomfortably warm in the summer and cold in the winter. On the other hand, boats with fiberglass hulls do not transmit heat well and are more comfortable.

When it comes to aesthetic appeal, fiberglass hulls have a sleeker, shinier, and more polished look. Steel hulls often have marks of reinforcements on their hulls and they need to get a nice paint to look good. In most cases, steel hulls are covered with putty to hide any construction defects. This putty should be polished so that the boat has a nice finish and is done in a controlled environment to keep out dust.

As you can imagine, this process is complex, costly, and drives up the price of the boat.

It is easier to manufacture fiberglass hulls and mold them into more complex shapes. This can lead to faster production and lower construction costs. Sailboats with steel hulls are more expensive, as we mentioned before because they require welding, heavy-duty grinding , and specialized cutting tools and are more labor-intensive.

When Should You Choose a Steel Boat?

Steel hulls are stronger, durable, and more impact-resistant than their fiberglass counterparts. Dents in steel hulls can be repaired easily and although steel is prone to corrosion, this can be managed by special paints, insulation, and some regular maintenance.

If you are deciding on a circumnavigation or want to go out on a long spree in the water, you need a solid and dependable boat that you can rely on when you venture into new territories.

A well-maintained sailboat gives you the confidence to enter into unfamiliar rocky coasts and reduce your worries about hitting UFOs. However, keep in mind that steel boats may be slower than fiberglass boats, particularly if they are smaller vessels.

When Should You Choose a Fiberglass Boat?

Fiberglass boats are generally prettier than steel boats since they have a smooth and polished hull. They also do not require protective paint on their hull since they are corrosion-free and hence quite low maintenance. In addition, they are lighter and faster than their steel counterparts and do not cost as much.

However, one big concern of a fiberglass hull is that it is not as strong as a steel hull. If the boat hits a hard object, the fiberglass may break, which can be dangerous on the open seas, particularly in choppy waters.

Still, fiberglass boats are an excellent option for racing and even long-distance cruising in areas that do not have sharp rocks.

The type of sailboat you choose depends on your sailing style and your needs. So make sure you consider all the factors before you invest in a steel or fiberglass boat.

Related Articles

Types of Sailboat Hulls

What Is a Sailboat Hull?

Jacob Collier

Born into a family of sailing enthusiasts, words like “ballast” and “jibing” were often a part of dinner conversations. These days Jacob sails a Hallberg-Rassy 44, having covered almost 6000 NM. While he’s made several voyages, his favorite one is the trip from California to Hawaii as it was his first fully independent voyage.

by this author

Learn About Sailboats

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

Daniel Wade

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

Steel Sailboats: The Ultimate Guide

Introduction:.

Embarking on a voyage of exploration, where the horizon stretches endlessly before you, requires a vessel that embodies the spirit of adventure. Enter steel sailboats, the rugged champions of the maritime world. In this article, we delve into the exhilarating pros and cons of steel hull sailboats, revealing their unmatched potential for daring adventurers and their ability to conquer the most treacherous waters on Earth.

Pros of Steel Sailboats:

Unyielding Strength:

When it comes to traversing untamed waters, the formidable strength of steel hulls becomes your most trusted ally. These vessels fearlessly navigate through icy Arctic fjords, daringly cut through gales of the roaring Southern Ocean, and elegantly glide across tropical lagoons. With their robust construction, steel hull sailboats provide unparalleled resilience against the elements, instilling unwavering confidence in explorers.

Conqueror of Varied Terrain:

Steel hull sailboats are versatile workhorses of the seas. They can gracefully sail through oceanic expanses, weave their way through winding rivers, and venture into shallow coastal areas inaccessible to other vessels. Whether you yearn for the wild isolation of remote islands or the tranquil beauty of hidden coves, a steel hull sailboat will carry you there, unveiling breathtaking vistas that remain hidden to those with lesser means.

Guardian of Safety and Security:

As an explorer, your peace of mind is paramount, and steel hull sailboats excel in providing just that. Their solid steel armor shields you from the unexpected perils lurking beneath the surface. From the menacing jaws of sharks to the unpredictability of floating debris, your steel hull sailboat acts as your faithful protector, allowing you to navigate with confidence and embrace the untamed beauty of uncharted waters.

Enduring Customization:

Steel hulls offer a blank canvas for explorers to imprint their dreams upon. Seamlessly adapting to your desires, these sailboats can be transformed into floating homes equipped with the latest technology, enabling you to fully immerse yourself in the expedition. Create additional storage for essential supplies, craft luxurious living spaces, or incorporate cutting-edge navigation systems—the possibilities are limited only by your imagination. Your steel hull sailboat becomes an extension of your indomitable spirit.

Cons of Steel Sailboats:

Embracing The Weight and Speed on Steel Sailboats:

It’s true that steel hulls tend to be heavier than those made from other materials, such as fiberglass or aluminum. The additional weight can slightly reduce the overall speed and agility of the sailboat. However, let it be known that the pursuit of adventure and exploration is not solely about speed. It’s about savoring the journey, immersing yourself in the surroundings, and relishing the sense of discovery. The steady grace and unwavering presence of a steel hull sailboat evoke a timeless spirit that resonates with true adventurers.

Tending to Maintenance:

Steel hull sailboats require diligent maintenance to prevent corrosion. Exposure to saltwater can accelerate the formation of rust, necessitating regular inspections and protective coatings. Yet, the care bestowed upon a steel hull sailboat is not a burden but rather a labor of love—a testament to the enduring relationship between an explorer and their vessel. The dedication invested in preserving its strength and beauty forms an unbreakable bond, strengthening your connection to the journey.

Considering Cost:

Steel hull sailboats are generally more expensive to build and maintain compared to vessels constructed from other materials. The initial investment for acquiring steel, skilled labor, and specialized equipment may be higher. However, the value of a steel hull sailboat lies not only in its monetary worth but in the experiences it grants you. The ability to conquer new horizons, witness breathtaking landscapes, and forge indelible memories—the cost becomes insignificant when weighed against the unparalleled adventures that await.

Unleashing the Potential: Where Steel Sailboats Can Take You

Roaming the High Seas in Steel Sailboats:

Steel hull sailboats boldly embrace the vastness of the open ocean. From circumnavigating the globe to exploring remote archipelagos, these vessels can take you to the farthest reaches of the world. Traverse the roaring forties, conquer the fabled Cape Horn , or witness the stunning migration of marine life across entire ocean basins. Your steel hull sailboat becomes a conduit to connect with the raw power and grandeur of the world’s oceans.

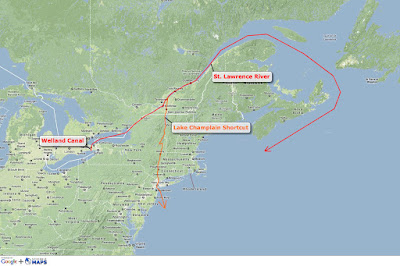

Exploring Inland Waterways:

Inland rivers and waterways unveil their secrets to intrepid explorers aboard steel hull sailboats. Journey through ancient river systems, winding through lush rainforests and towering canyons. Conquer the mighty Amazon, venture into the heart of Africa along the Nile, or navigate the tranquil canals of Europe, immersing yourself in diverse cultures and captivating landscapes along the way. With a steel hull sailboat, the world’s interior waterways become your personal playground.

Conclusion:

Steel hull sailboats epitomize the very essence of adventure and exploration. Their unwavering strength, unrivaled versatility, and indomitable spirit unlock a world of possibilities for daring voyagers. These vessels fearlessly navigate treacherous waters, embracing the unknown and guiding you to the most awe-inspiring corners of the Earth. Embrace the call of the wild, set sail on a steel hull sailboat, and let the winds of discovery carry you to destinations beyond your wildest dreams. The seas are waiting, and with a steel hull sailboat as your vessel, you are destined to conquer the uncharted and emerge as a true explorer of the world’s wonders.

Previous Post Van Life to Boat Life: Millennials Living on the Water

Next post the herreshoff legacy: yacht design and innovation pioneers, related posts.

The Equator

Perhaps you have already read our article about the best reasons to live on a boat and we managed to convince you? And now you are looking for a proper cruiser sailboat to turn your dream of living as a liveaboard into reality? Sooner or later, you will definitely ask yourself which hull material is most suitable for a cruiser and this is exactly the question we want to discuss in the following.

Table of Contents

What Materials Are Considered?

The materials used for hull construction of sailboats are GRP (glass fiber reinforced plastic), carbon, Kevlar, wood, aluminum, steel, ferrocement and also various hybrids of these. Some of these materials are not suitable for use in cruisers due to their specific characteristics. Carbon and Kevlar usually only play a role in extremely lightweight high-performance boats typically found in racing, not to mention that they are astronomically expensive.

Wood disqualifies itself due to the extremely costly maintenance and thus it is not practical for use in cruisers. Ferrocement never really caught on as a hull material and primarily played a role as an easy-to-handle material in DIY sailboat construction. This leaves GRP, aluminum, and steel as materials that come into question for us.

GRP vs. Aluminum vs. Steel

In the following, we will take a closer look at these three materials and compare them with each other under various aspects that are important for a cruiser.

GRP is the weakest of the three materials, especially when it comes to impact and abrasion resistance. However, the strength of GRP is highly dependent on its processing quality, as GRP can be laminated in very different ways, which can make for large differences in stability. For example, the first GRP boats built in the 1960s and 1970s often featured much thicker material thicknesses because people were not yet familiar with the material and this resulted in nearly indestructible hulls. There are also some manufacturers who additionally reinforce their GRP hulls with Kevlar or metal inserts. So, there are a lot of differences in terms of stability, but in general a GRP hull is clearly inferior to metal hulls in terms of stability.

In the video below you can see a few crash tests of a Dehler 31, which is made of GRP and takes the collisions impressively well.

Aluminum and steel hulls, on the other hand, have extremely high impact and abrasion resistance, with steel being even slightly superior to aluminum here, as steel is more elastic and has a higher tensile strength. Thus, a metal boat is much more robust and therefore safer than a GRP boat, especially in collisions.

GRP is far superior to steel in terms of weight. For boats up to about 40 feet, it is also superior to aluminum, since aluminum has a minimum thickness of about 5mm making smaller boats heavier than their GRP competitors. Above the 40-foot mark, the tide can turn, and aluminum may be lighter than GRP, but it depends on the exact construction.

Aluminum as a material itself weighs only about a third as much as steel, but the typical weight saving of a hull is typically 20-25% (but up to 50% savings are possible in some cases). This can be attributed to the fact that aluminum requires thicker material thicknesses than steel.

As should already be clear, steel boats are by far the heaviest of the materials we are considering here.

Sailing Characteristics

The sailing characteristics are of course not primarily dependent on the hull material, but rather on other characteristics such as the hull shape, the rig, etc. Nevertheless, certain characteristics are attributable to the hull material.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Oyster Yachts (@oysteryachts)

GRP boats sail very fast because of their low weight, but the residual flexibility that is unavoidable in the material can cause annoying creaking noises inside the boat.

Aluminum boats, on the other hand, also sail very fast, but much more stiffly and you are not plagued by creaking noises.

Steel also makes for stiff sailing and there are no creaking noises, but due to the enormous weight, a steel boat sails rather sluggishly. However, the high weight also gives steel boats good-natured sailing behavior, which is more likely to forgive too much sail area.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by WELTREISE | ABENTEUER | MEER (@bluehorizon_exploration)

Interior Space

Unlike metal hulls, a GRP hull does not need an internal reinforcement structure that reduces the space inside the boat. Thus, GRP boats offer a lot of interior space relative to their dimensions.

The stability of aluminum hulls, on the other hand, depends on an internal reinforcement structure (consisting of frames and stringers), which takes up some of the valuable space inside the boat. Especially for smaller boats this can be more important than you might think. In the image below you can see the construction of an aluminum hull built by Dutch shipyard KM Yachtbuilders.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by KM Yachtbuilders (@kmyachtbuilders)

Steel boats also need such a reinforcement structure, but it is much more compact than that of aluminum boats, thus offering more interior space.

Insulation Properties

Due to its sandwich construction, GRP is inherently a poor conductor of thermal energy and therefore requires little insulation and, under certain conditions, none at all. Along with the good insulating properties, GRP boats also have less condensation to contend with than their metal competitors. In addition, it also has good sound insulation.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Hallberg-Rassy (@hallbergrassy)

Aluminum and steel boats have very similar properties in terms of insulation. Both materials are very good thermal conductors, which makes good insulation essential. Due to the cold bridges found in metal boats, a lot of condensation occurs inside the boat. The sound insulation of metal hulls is also poor.

Visual Design Options

GRP hulls offer a lot of room for styling, since gelcoats are available in all possible colors and applying them is easy. Another big advantage of GRP is that round shapes can be realized very easily with this material, which makes ergonomics and design very appealing.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by beneteau_official (@beneteau_official)

In contrast to GRP boats, round shapes in metal boats can only be achieved with significantly more cost as this requires a lot of effort and special skill in welding. The many welds on metal boats can in some cases look rather rustic, which may bother some people.

Aluminum hulls usually leave the shipyard unpainted, as painting them is very time-consuming and expensive and therefore rather unusual. The raw aluminum look does not appeal to everyone.

Steel boats can be painted as desired, but they almost always have minor visual rust spots somewhere, which are hardly avoidable.

Safety During Thunderstorms

Unlike metal boats, a GRP boat offers no protection to the boat, equipment, and crew against lightning strikes, and you are dependent on a proper lightning conductor system.

In contrast, boats made of aluminum and steel provide excellent protection against lightning strikes purely due to their construction, because they act as a Faraday cage – the inside of the electric field created by a lightning strike is reliably shielded.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Energy Observer (@energyobserver)

Risk of Material Decomposition

A known risk of material degradation of GRP is osmosis, which occurs when the hull is not properly protected, and moisture can penetrate through the gelcoat where the moisture collects in the hull cavities. The resin in the laminate is decomposed by the penetrated moisture and an acid is produced. Due to its chemical properties, it draws further moisture into the cavities. The pressure in these then increases and pushes the gelcoat outward forming blisters. The brittle gelcoat cracks open and the laminate is progressively decomposed as osmosis continues.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by @sailinghuakai

However, we want to emphasize that osmosis is often overdramatized, and we are not yet aware of any case where a boat has actually sunk because of osmosis. Nevertheless, you should not underestimate this danger and prevent it from happening in the first place through proper care. Unfortunately, structural defects in the hull of used boats caused by osmosis are difficult to see as a non-expert.

In the case of aluminum, there is a risk of galvanic corrosion, in which the base metal aluminum decomposes under the influence of electric current when it comes into contact with a more noble metal. Although such galvanic corrosion can cause considerable damage to the boat within a very short time, this risk can be virtually eliminated if the boat is professionally constructed and regularly maintained. However, this means that any electrical leakage currents must be eliminated, and the many sacrificial anodes must be maintained. Besides, when it comes to electrical installations, you need to know what you’re doing.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Gate Service Barcelona (@gateservicebarcelona)

Steel is generally known to be very susceptible to corrosion. Once steel comes into contact with oxygen in the presence of water, rust forms as a result of oxidation. As owner of a steel boat, there is not much you can do against the constant danger of corrosion, except to always make sure that the steel is protected from external elements, which requires a lot of maintenance. In addition, it should be emphasized that the greatest danger of corrosion is the rusting through of the hull from the inside to the outside and not the other way around. Often it is difficult to see all the areas inside the hull and this harbors some undetected dangers.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Fundacja Klasyczne Jachty (@klasycznejachty)

Repairability

Even fairly extensive damages in the GRP can be repaired quickly and easily because all you need are fiberglass mats, resin, and hardener. Minor blemishes in the gelcoat such as scratches or small chipping can be repaired with ease.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Manta Marine Services Goa (@manta_marine_services_goa)

Repairing aluminum, on the other hand, is much more difficult, because you first need aluminum plates with the right alloy, and then you also need the right welding equipment. In addition, not everyone has the necessary know-how to weld aluminum properly. Minor blemishes such as scratches can be polished, and dents can be attempted to bulge from the inside. However, if you can’t get to the dent from the inside, you’ll have to live with it willy-nilly.

Steel must be welded as well, but suitable steel plates can be found in most workshops around the world and welding is also much easier than welding aluminum. In addition, the required welding equipment is cheaper and more widely available. The repair of scratches can be easily done yourself, but this is often much more time-consuming than repairing the gelcoat on GRP boats. Dents can be attempted to be removed in the same way as with aluminum boats.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Dimos Ganiatsas (@dimosgan)

Maintenance Effort

The maintenance effort is kept within limits with GRP. You should just sand, fill and seal the underwater hull regularly. The great thing about GRP is that such maintenance can be postponed once in a while without having to fear immediately serious consequences (but don’t let it become a habit!).

View this post on Instagram A post shared by SailingJoa (@sailingjoa)

Aluminum boats also require little maintenance, as you only need to regularly renew the antifouling coating and maintain the numerous sacrificial anodes, as well as ensure that there is no potential for galvanic corrosion. However, unlike GRP, the maintenance of aluminum boats allows significantly less time leeway, because if galvanic corrosion does occur, it can cause significant damage in a very short period of time.

Steel boats, unlike GRP and aluminum, require constant maintenance, as there are virtually always some rust spots that should be treated early to prevent worse. At regular intervals, the entire hull should also be sand stripped followed by priming with an epoxy system and then sealing with a paint (polyurethane based). Although a steel hull does not rust as quickly as aluminum does with galvanic corrosion, you should avoid postponing maintenance for anything, otherwise nasty surprises can await you.

The cost of GRP boats, from serial and semi-custom production is the lowest compared to those for metal boats. This is mainly due to the fact that a mold only needs to be designed once, which can then be used for all builds of the model. Custom builds, on the other hand, cost significantly more because a mold must be made individually, which involves high costs.

Metal boats are more expensive in serial production as they require a lot of manual welding, with aluminum being even more expensive than steel due to the more complex processing and higher material prices. However, metal boats can be more attractive than GRP for custom builds, but it depends on the individual project.

In addition, it can be said that aluminum boats have a very good value retention compared to GRP and steel boats, which is also reflected in the second-hand market. On the second-hand market, aluminum boats are usually traded at very high prices, whereas GRP boats depreciate significantly and there is a large supply at low prices. The supply of steel boats is rather limited, but the prices for them are nevertheless rather low.

Besides these initial costs, you should also always consider the follow-up costs, because these can make a lot of difference in the long run, especially when you look at the differences in maintenance requirements. Consider how much time and money you will have to put into the boat and even if you want to do most of it yourself, keep your individual opportunity costs in mind.

A Summarizing Overview

In the table below, we have briefly summarized the various characteristics of the respective materials.

| GRP | Aluminum | Steel | |

|---|---|---|---|

| + | ++ | +++ | |

| +++ | ++ | + | |

| +++ | +++ | + | |

| +++ | + | ++ | |

| +++ | + | + | |

| +++ | + | ++ | |

| + | +++ | +++ | |

| ++ | ++ | + | |

| +++ | + | ++ | |

| +++ | +++ | + | |

| +++ | + | ++ |

An Important Note

Finally, we want to note that there is no such thing as the perfect hull material, because as we have pointed out, each has its strengths and weaknesses. Keep in mind that the properties of the various materials we have discussed are the general ones that apply to most boats. However, the properties of a hull also depend on the specific boat because construction and quality of workmanship are at least as important as the material itself. When comparing different hull materials, you should always keep these differences in terms of construction and workmanship in mind and not compare apples with oranges. It would not make sense to compare a production GRP boat produced under cost pressure with a custom aluminum boat and then conclude that the GRP boat is inferior to the aluminum boat.

Our Recommendation

In general, we claim that for the majority of people a GRP boat makes the most sense. It is very user-friendly in both use and maintenance and is also relatively affordable. We see no reasons against the use in bluewater or for a circumnavigation, although this scene is strongly influenced by advocates of metal boats. We can certainly understand the aspect of increased safety of metal boats, especially in collisions, but we doubt that this justifies the disadvantages of steel or the additional costs of aluminum. Severe collisions are of course a high risk, but always keep in mind how low the probability of such a collision actually is. Nevertheless, we can understand that the increased sense of safety is a very high priority for some.

When using the boat under extreme conditions, such as in Antarctica or Patagonia, we would also want to use a metal boat due to its increased robustness. So, it’s best to ask yourself honestly which areas you actually want to sail.

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Live To Sail (@live_to_sail)

In addition, you should also let your own skills and experiences that you have made with the respective material flow into the decision-making process. For example, if you have had a lot of professional experience with steel processing, then you will see the work involved in a steel boat from a completely different perspective… In this sense, listen a little to your gut feeling.

And last but not least, as already mentioned above, it always depends on the specific boat and especially if you are on the second-hand market, you can certainly be a little more flexible with regard to the choice of material and look at the overall package. But we hope that we could help you understand what to expect from the different materials and assist you in making your decision.

If you have any other questions, need advice on your upcoming boat purchase, or want to give us feedback, feel free to post it in the comments, we’ll try to answer everyone!

Happy sailing!

Leave the first comment (Cancel Reply)

Stay on topic.

7. July 2022, updated 5. August 2024

Bluewater Cruising With a Powerboat Instead of a Sailboat?

17. June 2022, updated 21. July 2022

Starlink Is a Game Changer for Maritime Internet on Boats

17. June 2022, updated 17. June 2022

The Best Reasons to Become a Liveaboard

Filter by topics.

- — Cruising-Liveaboard

- — Powerboating

- — Sailing

- — People

- — Places

- — Products

- Marine Environment

- — Impressions

- — Sustainability

When it comes to real bluewater cruising, like ocean crossings or even circumnavigations, sailboats are clearly more common than powerboats. But let’s be honest, many sailors start the engine as soon as there is a calm. On most sailboats, the engine is certainly no longer just an auxiliary propulsion for harbor maneuvers, but rather a…

Nowadays, you hardly have to sacrifice anything when living on board, and you have access to almost all the things you’re used to from life on land. Unfortunately, fast, reliable, and widely available Internet, which on top of that is reasonably affordable, is still a big challenge. Especially for people who want to do remote…

Here at Maritime Affection, we all have a deep affection for the maritime life. But what to do when this affection has become an inseparable love? It’s simple: become a liveaboard and experience the ultimate freedom right on the water! Especially in the last years of the epidemic, many people have become interested in living…

16. June 2022, updated 22. April 2024

Greenland Shark: 400-Year-Old Hunter in the Arctic

Sharks fascinate many people and are probably one of the most famous sea creatures. Mostly they are known for their impressive predatory abilities, but do you already know the Greenland shark? What makes it special is that it is the longest living vertebrate known, with at least 400 years. Hard to believe and incredibly fascinating…

29. May 2022, updated 30. May 2022

Guidelines to Prepare for Maritime Crime and Piracy

The biggest fear of many boaters, especially those on circumnavigation or other long voyages, is to experience a pirate attack on the high seas. In addition, kidnappings involving ransom, robberies, burglaries, and thefts cause worries among crews. These worries are definitely not unfounded and therefore it makes sense to familiarize yourself with these risks and…

28. May 2022, updated 29. June 2022

Sailing Cruiser: Monohull vs. Catamaran

Whether you plan to buy a sailboat to sail around the world, become a full-time liveaboard, or just occasionally go on nice sailing trips with the family, you will be confronted at some point with the question of whether it should be a monohull or a catamaran. With this article, we want to help you…

23. May 2022, updated 18. July 2022

End-Of-Life Boats, an Urgent Issue That We Must Solve

Although the idea may hurt, every boat eventually reaches the end of its lifecycle and must be disposed of accordingly. In contrast to many other things, which we can nowadays easily get rid of and usually even recycle the majority of, this is far more difficult with boats and therefore more expensive. Consequently, many end-of-life…

16. May 2022, updated 17. June 2022

Why Size Doesn’t Matter When It Comes to Your First Own Boat

For many of you maritime enthusiasts sooner or later the desire for your own boat arises. We felt the same way and we are also enthusiastic boaters! But if you are a newcomer to the world of boating, you can quickly be frustrated or disappointed by unrealistic expectations regarding financial and organizational aspects, and you…

13. May 2022, updated 22. April 2024

The Ultimate Guideline for Sustainable Boating

More and more people are developing an awareness of the dramatic marine environmental problems and are trying to live more sustainably. Also, in global politics the discussion around marine sustainability becomes more and more important and the boating industry is regulated by increasingly strict laws. Especially when you are boating, there are many small things…

28. April 2022, updated 31. May 2022

Sausalito, CA: the Perfect Maritime Getaway

If you ever find yourself in the San Francisco Bay Area, we have a beautiful place for you that is guaranteed to make your maritime heart beat faster. We’re talking about the charming town of Sausalito, 6.4 km (4 miles) north of San Francisco. There’ s a strong maritime feel to Sausalito, no matter where…

Attainable Adventure Cruising

The Offshore Voyaging Reference Site

- Hull Materials, Which Is Best?

As Phyllis and I think about what our next boat might look like, one of the primary decisions is hull material.

We have several chapters in this Online Book about the characteristics of the four general available options, steel, aluminum, wood and fibreglass (see Further Reading below), but that still leaves the question: Which is best, not just for Phyllis and me, but for you, too?

As usual, the answer is the oh so annoying: it depends on what we plan to do with the boat.

But what I can say, is that there are two materials that are pretty easy for Phyllis and me to drop from the hull materials prospect list. So let’s start with that, and then move on to the two left standing to pick a winner.

Hull Material We Won’t Consider

We will not even be looking at boats made of steel or wood—not quite true, we might consider a good wood epoxy saturation build—and that’s also our advice to most of you.

Why neither of those two materials? Both are intrinsically unstable. Or, to put it another way, no matter how well the boat is built, if left to their own devices, wood will rot and steel will turn into a pile of iron oxide.

OK, before you take me to the woodshed in the comments, let me make clear that I understand that good boats can be built of both wood and steel.

One of my good friends has a wooden boat that has given great service (including a bunch of ocean crossings) for decades, and will continue to do so for many more. But he built her himself, has cared for her meticulously, and has incredible skills. But I’m not Wilson (that’s his name) and, in all likelihood, neither are you.

The same applies to steel. If you built the boat yourself, or supervised every step of the build, and then cared for her yourself, it can work. Just look at the amazing voyages made by AAC contributor Trevor Robertson in Iron Bark .

But we are talking about second-hand boats for most of us, so steel and wood are out because it’s difficult to be reasonably sure in a pre-purchase survey on either material that something horrible is not going on deep within the structure. Something that, when discovered, can turn our new-to-us boat into a worthless pile of junk—we are talking the risk of serious wealth destruction here.

Still not convinced? Let’s dig deeper.

There’s another big problem with wood. If we find say a rotten stern post, or any other structural member after purchase, the skills and time to replace it are prodigious. Heck, just replacing a single plank in a way that will actually be watertight takes great skill and perseverance. Way beyond practical DIY for most of us. And I have seen professional replacement of just a few rotten members in a wooden boat cost over US$100,000.

What about steel? Well, on the positive side, repairs require less skill than wood. But the problem is it is very difficult to build a boat of steel under about 45 to 50 feet that will sail or motor well. The reason is that steel plating must be of a certain minimum thickness to be workable and not deform, regardless of boat size, so small steel boats are pretty much always too heavy, at least for the performance that Phyllis and I want.

And, finally, the maintenance of a steel boat is simply no fun—unless you have some perverted love of chipping rust and working with toxic chemicals—and to make that worse, any breach of the coating must be dealt with promptly and properly.

The bottom line is that I know a lot of people who own a steel boat, or have done so in the past, but I have never met anyone who has owned a second steel boat.

All that said, I guess purchasing a steel or wood boat with a history like those I mention above, from someone you really trust, would be OK—particularly if you make clear that if they have lied to you, you will hunt them down and… And the advantage of this course is that you can often get a lot of boat for very little money.

Hull Materials We Will Consider

Where does that leave Phyllis and me, and probably you, too? Yup, with fibreglass and aluminum. Both are intrinsically stable—assuming we don’t do something stupid, and, when built right, a hull of either does not deteriorate just because of the passage of time.

And both can be surveyed prior to purchase to make fairly sure (there is no certainty) that there is not something horrible lurking. Yes, I know there are many horror stories (I have one of my own) about fibreglass boats with hidden faults, but that’s a survey failure, not a material one. (More on how to avoid survey failures coming soon.)

So which is best, aluminum or fibreglass? Brace yourself. I’m going to do it to you again. It depends on what you want to do. Let’s look at each.

As a 30 year aluminum boat owner, I love the material. And if Phyllis and I were planning to go to seriously hazardous places (as we have in the past), aluminum would be our only choice.

But on the other hand, aluminum is a bitch to keep paint on, an expensive bitch. And, by the way, don’t think for a moment that leaving the hull bare solves that. Prepping and painting the deck and cabin of an aluminum boat to the yacht standard that many owners want and want to maintain, will, if done right by professionals, cost as much or more than painting an entire fibreglass boat.

The point being that if you are considering aluminum, you need to do as I do: take your glasses off when you see the paint bubbling. Or, better yet, seriously embrace the industrial look and have no paint on deck or hull, other than non-skid.

Also, although there is no question that most of the horror stories you hear about aluminum are just that—stories—the material does require caring for, including closely supervising anyone who works on the boat. Most boatyard professionals are dangerously ignorant about aluminum and many will make that worse by not appreciating their own ignorance.

So that leaves fibreglass. And for Phyllis and me, who now want a boat that we can safely leave unattended far from home—we are now part-time cruisers—that’s the way to go.

Also, as we age further, we will be paying boatyards to do more and more for us, another plus for fibreglass, since it’s more resistant to unsupervised ignorance—boats with core in the hull, particularly balsa, not so much—than aluminum.

Bottom line, if you are not willing to learn the basics of aluminum boat care and won’t be constantly present to rigorously enforce that knowledge on others, choose fibreglass. On the other hand, the good news is that said aluminum boat care is not hard, and not magic. See Further Reading for our complete guide.

I’m guessing that many of you steel boat owners are now seething and reaching for your keyboards to tear me a new one. Feel free to disagree and tell me why steel is great, but be realistic.

And please keep in mind that we have a lot of readers who do not have a lot of boat ownership experience. So if you blow sunshine about the issues with steel boats, particularly old steel boats, you may make yourself feel better, but you may also tip someone into a life altering decision with substantial negative consequences. Not something any of us need on our conscience.

Further Reading

- How to care for an aluminum boat in 27 easy steps.

- Much more on buying a boat .

- How to care for a cruising boat, once you have bought her.

- The engineering characteristics of hull materials.

- Impact resistance and why it matters .

- More on boats from Boreal .

- More on Ovnis .

Please Share a Link:

More Articles From Online Book: How To Buy a Cruising Boat:

- The Right Way to Buy a Boat…And The Wrong Way

- Is It a Need or a Want?

- Buying a Boat—A Different Way To Think About Price

- Buying a Cruising Boat—Five Tips for The Half-Assed Option

- Are Refits Worth It?

- Buying a Boat—Never Say Never

- Selecting The Right Hull Form

- Five Ways That Bad Boats Happen

- How Weight Affects Boat Performance and Motion Comfort

- Easily Driven Boats Are Better

- 12 Tips To Avoid Ruining Our Easily Driven Sailboat

- Learn From The Designers

- You May Need a Bigger Boat Than You Think

- Sail Area: Overlap, Multihulls, And Racing Rules

- 8 Tips For a Great Cruising Boat Interior Arrangement

- Of Cockpits, Wheelhouses And Engine Rooms

- Offshore Sailboat Keel Types

- Cockpits—Part 1, Safe and Seamanlike

- Cockpits—Part 2, Visibility and Ergonomics

- Offshore Sailboat Winches, Selection and Positioning

- Choosing a Cruising Boat—Shelter

- Choosing A Cruising Boat—Shade and Ventilation

- Pitfalls to Avoid When Buying a New Voyaging Boat

- Cyclical Loading: Why Offshore Sailing Is So Hard On A Boat

- Cycle Loading—8 Tips for Boat and Gear Purchases

- Characteristics of Boat Building Materials

- Impact Resistance—How Hull Materials Respond to Impacts

- Impact Resistance—Two Collision Scenarios

- The Five Things We Need to Check When Buying a Boat

- Six Warnings About Buying Fibreglass Boats

- Buying a Fibreglass Boat—Hiring a Surveyor and Managing the Survey

- What We Need to Know About Moisture Meters and Wet Fibreglass Laminate

- US$30,000 Starter Cruiser—Part 2, The Boat We Bought

- Q&A, What’s the Maximum Sailboat Size For a Couple?

- At What Age should You Stop Sailing And Buy a Motorboat?

- A Motorsailer For Offshore Voyaging?

- The Two Biggest Lies Yacht Brokers Tell

What are the hull and deck panel thicknesses on MC?

As I remember, hull 1/4 to 3/8 in the keel. deck 3/16″. That said just looking at plate thickness does not tell you a lot. For example MC is built with very closely spaced frames and stringers which add a lot of strength but less weight than heavier plate and fewer frames and stringers.

John, I hear your warnings about steel, and I know this might be a complicated route to go. My main reservations about fiberglass boats is that the majority of them come with external keels which is fine for me for a one or two weeks charter but something I absolutely do not want for my own future boat. Encapsulated keel structure (or welded on as with steel hulls), a deep V forefoot, and a rugged skegged rudder, are characteristics that can more often be found with steel hulls as with “plastics”. When going for my survey I plan to come with a fiber optic to inspect all those remote places, and would certainly rule out a boat where I would not have access to most if not all hull places. That said, if I were to buy now, my current favourite on the market is a fiberglass ketch 😉

I would not recommend discarding all external keel boats from your list. Yes, the modern trend to bolting through light skins and then using a glued in web to stiffen things up is intrinsically dangerous, but there are plenty of external ballast boats that are built properly.

And internal ballast is not without problems. Like with most things it all depends on the execution.

And there are good hull forms in GRP too. In fact, in my experience, a lot of steel boats are designed very poorly.

Anyway, I would not take on the risk and maintenance burden of a second hand steel boat for those reasons.

Agree with everything you say about steel boats. When I got back from Vietnam in 1969, I took all of my savings and bought a steel 45 steel schooner and lived on her. I went to work at the Naval base in Pensacola, FL and left my wife to chip, sand and paint the rust spots that seemingly appeared almost every day inside and outside ( no wonder she divorced me! ) I finally sold the boat to a “know it all” and bought a Hinckley 50 fiberglass yawl — problem solved!

Hi Patrick,

Thanks for the report. Another person who has owned one steel boat!

I totally agree with your conclusions on this. No material is perfect but fiberglass has a lot to be said for it overall and aluminum is great when a bit extra is required. Aluminum is actually the only material you have listed that I really don’t have much experience with beyond little skiffs so it is the one I can’t properly comment on but I like the concept.

I have had a lot of interactions with wooden boats including having a good sized one in the family and working aboard several. While I love these boats and think they look great, our boat is fiberglass and that is intentional. For that matter, our boat doesn’t have any wood on deck at all. With wooden boats, like most things, it really comes down to who the owner is. An owner who gets it and stays ahead of maintenance puts in surprisingly little time (still a whole lot) dealing with rot and paint that won’t stick. An owner who is a little less vigilant and deals with a deck leak by hanging a diaper under it rather than getting out their irons to fix it will find the boat falls apart on them incredibly quickly. In my experience which is all salt water based, deck leaks are the biggest killer of these boats by far and they are actually comparably one of the easiest to track down and fix. Even for an owner who farms out the wood work, I would say that if you can’t fix a deck leak and don’t have oodles of money, then it is a disaster waiting to happen.

With steel boats, all I have to say is that I hate the sound of a needle scaler. If you have a ton of money, there are great examples like the Columbia replica but that is not attainable for most of us.

I realize that there are a lot of people who get very nervous with keel bolts (and bolts in general in anchors and other things) and while it is something to watch, I think that it is a good trade-off given the other options. I think that a lot of the issue is that the average person does not know how to evaluate whether a bolted connection is a good connection and there have been an awful lot of poor connections built over the years. An example of a good connection is most connecting rod bolts which have enormous numbers of cycles, vibration and other factors to contend with but yet basically never fail unless there is another underlying issue such as the caps being mixed up. By getting the bolt stretch length long enough, using appropriate materials, having appropriate mating threads and using enough torque/tension, you end up with bolts that don’t back out and do not fatigue. Keels are a bit tricky as very few materials won’t suffer from some sort of corrosion if there is any water and fiberglass creeps so it is difficult to maintain constant tension but I think that you would find an extremely low failure rate on well designed connections and that most of the failures were on connections where an analysis would have shown that the margins were low and best design practices were not followed.

On wooden boats, although I have little first hand experience, as you say, and I see demonstrated by Wilson, a skilled and diligent wooden boat owner can make the maintenance look easy, but let a wooden boat get away from you and there will be tears.

On keel bolts, a question for you? If contemplating buying an old boat with external ballast, would it make sense to insist that before purchase the keel bolts (assuming accessibility) were torqued to the proper value for their material and size?

My thinking is that, assuming the construction and bolts were right when built, the biggest risk, particularly with SS bolts, is that they have wasted at the keel to deck joint due to water ingress, so if they withstand the appropriate torque without breaking we can be pretty sure that that they are not appreciably weakened. Does that make sense?

I would make no such assumption about the keel bolts. They may be seized, in which case you’ll see the correct reading on the torque wrench but the pre-load tension in the bolt will be wrong. They may also be partially corroded, in which case they may withstand the torque but still be capable of failing in tension if the boat were to, for example, ground on a reef.

If it’s possible to get at them to check their torque, it shouldn’t take much longer to completely remove the nuts, one at a time, to check the studs or the cavities for signs of corrosion before re-torquing them to the proper specs. If it’s not possible to do this, then it’ll be difficult for *any* non-destructive examination to reveal what you want to see.

Thanks for coming up on that. How about just loosening a half turn and then torquing to spec? What I’m trying to come up with here is a way to at least check for a really bad keel boat situation in a way that will be acceptable before purchase, and I fear that if we try and actually remove the nuts and backer plates the seller will reject the idea—just torquing the bolts is going to be a hard enough sell.

So, I get that the bolts may still be a long way from original after this test, but at least it will catch the ones that have corroded really badly. Also, I’m not sure that removing the nuts would tell us much since the bad bolts I have seen were corroded where the keel meets the hull, but would have looked fine from above, even with the nuts off.

Bottom line, I get that this is not a great solution, but my thinking is that it’s practical and a lot better than nothing. Would you agree?

Pull a few and inspect is probably the only real way to to be sure. At least this is done on a woodenboat.

Ignoring whether a seller will or should allow retorquing keel bolts, the theory is good but the practice is somewhat more problematic. Proof testing is a well established industry practice that has proven to be pretty effective. Periodic hydrotesting of pressure vessels such as boilers, tanks, etc is just one example of something that has been successful at eliminating a lot of dangerous failures.

The first practical issue is what torque do you apply. I design capital equipment not sailboats so don’t know exactly what is done as there are multiple schools of thought but if I were designing one of these joints, I would figure out my worst case loads, choose a preload of ~2X and then upsize the bolts from there a bunch to give a corrosion allowance but not increase the preload any more. The question is, what was done on the boat you are looking at. The average person does not have the knowledge to calculate what the maximum per bolt load is and then we don’t know the factors from there. I suspect that there are some boats out there where the torque value from the factory is 75% of yield just like most bolts are but I also suspect there are a lot of boats out there where the preload will be more on the order of 30% (I have it written down at home but I believe this is approximately what I calculated for ours with the assumptions I made). In the case where the designer did not leave a corrosion allowance, then a torque to 75% of yield is entirely appropriate but on other boats, you could break a bolt which while corroded was actually still well within allowable parameters or you could crush the laminate if there is insufficient load distribution for the higher tension. All of this can be calculated with fairly simple calculations but having anybody without training apply it is problematic and even then, you are really doing a proof test not just a retorque as you likely won’t know the original torque. If anyone knows of a standard that all designers hold to so a way to avoid the guessing game of the factory torque, I would love to know it.

The other practical issue that comes to mind is the imperfect relationship between torque and tension. Engineers refer to this relationship as K factor which is basically friction between the threads and the faces. When tension is really critical, the standard thing to do is to actually use oil or grease which are more repeatable and represent a lower K factor. If there has been any galling at all which is a real problem with stainless, all bets are off and you could even break the bolts before bottoming out if it is really bad. This is really the long way of saying that it is really inexact if you do it dry, you would really want to clean everything well and then oil the threads. Of course, if you are NASA, then you can actually measure tension on the bolts but everyone else is left using torque as a proxy.

Given all of this, I am not sure that most sellers could be made to agree to a specific torque number unless original build documentation can be found with a number which I don’t think that I have ever seen (unfortunate and kind of scary). Retorquing is definitely not a bad idea and I have done it on our boat, I just don’t know how to implement it simply and quickly unless someone knows that all keel bolts were originally torqued to some % of yield or something equivalent.

Hi Eric (and Matt),

Thanks for going to all the trouble to explain that. As so often happens, I’m a lot wiser after reading your and Matts thoughts. And clearly my idea is not a good one.

The sad part about that is that I think those of us considering an older boat may have a real problem that’s not generally recognized: Having wandered around boat yards a lot lately, I’m seeing a lot of otherwise good looking boats with stains indicating that water has penetrated between the keel and hull. I’m also guessing that a lot of boats for sale have had those stains covered up with paint.

Add in that many of those boats will have stainless steel keel bolts and I’m starting to think that the only good answer with a boat like that is going to be to drop the keel to check the bolts before heading offshore.

Of course we will not be allowed to do that before purchase, so that leaves walking away from a lot of good boats, or assume the risk. And the risk is not trivial. If the bolts are bad, replacement can be a serious matter. One experienced person at a quality builder said that the best and least expensive solution is to recast the keel with new bolts! The point being that most keels have J bolts cast in, and he said that hacking them out is a disaster—he has seen it tried.

So the more I think about this, the more I think that a lot of people who think they have refitted their boat for sea may in fact be sitting on a pretty nasty problem that would be hugely expensive to fix. And that as the years go by, this is only going to get worse. (A lot like the problems with SS in old rudders.)

I would really appreciate any other ideas of how to deal with this, or alternatively reassurance that I’m overthinking this. Also, do you think bronze keel bolts relieve at least some of this worry? With SS all I can think about is those bolts sitting in a wet oxygen deprived environment for 30-40 years! How about industrial x-ray? Expensive, I imagine, but probably a hell of a lot less than a keel bolt replacement.

John, you just elaborated very wisely the reasons why I will certainly not be looking for a boat with an external keel. You just can’t look inside (and I doubt even industrial xray could reliably see cast-in bolts). It is just like playing lottery, and what I learnt is at least that I will never win 😉 You’re right that encapsulated ballasts have their own issues, but at least they cannot fall off during a passage.

Your call, but what I’m finding is that there are so few really good boats out there for sale that even come close to my critical needs that to settle on a single keel construction type would limit my choices. This is particularly true since I want a boat with good performance, which is harder to do with an encapsulated keel, particularly in GRP.

Also, a boat with a bad encapsulated keel can be really bad. Think steel punchings in concrete. If that lot gets cooking and splits the outer sheath (I have seen 3 of these in the last month while wandering around boat yards) the repair would be way harder than new keel bolts. Just think about jack hammering out all that stuff!

Point being there are good boats built both ways, ditto bad boats.

Just to clarify, I was not asking about X-raying the bolts inside the lead. The problems I have seen are wasting in the hull to keel joint and a bit above. Seems like X-rays would pass through the GRP and show the bolt, but then again I have no clue, which is why I asked the engineers. As I remember Matt has worked on medical imaging equipment, so we may easily get a good answer.

Hi John, Your question highlights for me that another valid comparison (apart from hull material) might be long run production boats vs short run / custom boats. Long run production yachts of course favour fibreglass of course and tend to have more than a few things worked out over time – one of which is to make them as “charter friendly” (aka idiot proof), as possible. But am I right in my supposition that for this reason, most long run production boats will have steel keels, secured with stainless bolts tapped down into the metal keel? And short run designs (not generally being for charter markets) take advantage of the performance gain with lead keels, but have studs penetrating up through the hull, with securing nuts? Reading between the lines of Matt and Erics’ responses, it seems you must remove the keel to really check the studs on a lead keel and even then there could be something lurking deeper inside. Conversely, to check the keel bolts in a steel keel yacht, you could simply specify removing say 25% of the bolts at pre-purchase survey time. For total peace-of-mind, replacing all the keel bolts on our Beneteau 473 with original OEM bolts costs about $200 US, available ex-stock from the Beneteau Spares web-site (as are most other parts by the way, even now 15 years since launch). Now I get there are pro’s and cons of lead vs steel keels. But the simplicity and integrity of a steel keel is really hard to beat. I know of a Beneteau 473 that hit a rock doing 8-9 knots under motor, coming to a crash stop. The only damage the surveyor could find on the Monday (up on the hard) was a fleck of anti-foul chipped off. No gap in the hull joint, no weeping at the keel / hull join, no cracking in the anti-foul. Internally, no damage to the lay up or the supporting girders either. No harm, no foul as they say in America. So how about a long run production boat, John? br. Rob ps – no, it wasn’t our B473!

That’s a good point although I do wonder about the actual practicality of unscrewing a keel bolt that’s been imbedded in steel for years without it shearing off. I guess it would depend on how well the original builder had treated the bolt threads with an anti-seize of some type. As usual, we are at the mercy of the builder’s QC since one small mistake in construction can lead to a world of hurt 20 years later.

And good to hear that a Beneteau withstood a grounding so well. However, I would not want the impression left that this is always the case with boats from Beneteau since at least some of their later boats are built with a keel construction technique that is fundamentally dangerous, particularly after a grounding: https://www.morganscloud.com/2014/06/05/cheeki-rafiki-tragedy-time-for-changes/

I also need to point out that if the boat in question was built using the same methods as “Cheeki Rafike” there is no practical way to know for sure that she was not damaged.

(Both are conclusions from the report on “Cheeki Rafike” and engineering done my the Wolfson Unit at Southampton University. https://www.morganscloud.com/2015/06/25/cheeki-rafiki-report-misses-an-opportunity-to-make-boats-safer/

All that said, I have no problem with the idea of a production boat and have thought about several. In fact, as you say, there are a lot of advantages to one, particularly later in the series when the bugs have been worked out.

I think you could get pretty good contrast and detail of a set of keel bolts in cross-section via X-ray, given sufficiently high quality X-ray equipment. And if the X-ray crew has access to a megavoltage source like Co-60, you’ll be able to see the bolts cast into the lead quite clearly.

This is not going to be cheap, however. And whether it tells you anything useful will really depend on the exact design of that particular boat.

You could try ultrasound, but that’s highly dependent on the technician’s skill and on the access situation for that hull.

If stainless steel, or galvanized mild steel, bolts are cast into the keel (forming studs that protrude into the boat), and there’s evidence of water intrusion, then I think dropping the keel a few inches is the only reliable way to tell the extent of damage.

With lead keels, bronze bolts are definitely the correct choice; the bronze/lead combination is basically indestructible for more than the life of the hull.

Galvanized mild steel bolts with a cast iron keel also seem to be OK as long as the bolts are accessible for periodic replacement, and I’d definitely undo one or two to check during pre-purchase survey. Stainless makes me nervous. Bronze bolts with a cast-iron keel make me nervous.

Don Casey has a good article on assessing keel joint issues here: https://www.sailmagazine.com/diy/how-secure-is-your-keel

Thanks for that great information. Sounds like there’s nothing for it but to plan to drop the keel unless it’s bronze bolts into lead. Good to know what the reality is.

Thanks for linking to that article. I’m way better informed after reading it. Casey is the real deal.

Thanks for posting link to Don Casey’s article.

I was worried what you would ask what to do about it. Unfortunately, I don’t have great ideas beyond actually taking a look. I work on the design side of things and so don’t know a lot about non-destructive testing other than where I need to make allowances for it to be done (this is something that is definitely not done in the design of these joints). My experience with X-ray is limited to inspection of welds and castings and I am not sure how it would work on keel bolts so I can’t really add anything beyond what Matt said. I believe that there are also design solutions to make this a much smaller concern that could involve changing materials, designing to be inspectable, designing to be repairable (iron keels that are tapped and bolted from the top being an example), etc but that doesn’t deal with the already built boats.

In my case, there are a few things that made me feel comfortable with our boat. Looking at the ISAF statistics compiled in 2013, of 72 recorded keel failures, only 3 could be attributed to the bolts (important to note that 40 were undefined so the actual number could well be higher). Weld failures, and internal structure failures both had a more than double incidence ratio. I actually find this failure rate pretty low given the number of poorly designed (or designed with low margin for racing), poorly maintained and poorly repaired joints out there. Our boat has a pretty conservative keel attachment, the lever arm is small and the attachment is wide in both directions and the bolts are large. Given that, I calculated the required bolt strength and then looked at the bolt size on our boat and concluded that the designer had been appropriately conservative in upsizing to allow for corrosion. Next, our boat did not show any of the problem signs such as large rust streaks, signs of grounding damage, etc. Finally, I did exactly the test that you were hoping to do which is a torque test on all of these bolts (note, this and all the calculations were done post purchase) to values I calculated and felt comfortable with. Obviously this is not perfect but has mitigated the risk to a level where I feel there are other more important places to put my efforts.

Actually pulling the keel in a properly equipped yard is not that big of a deal, often on the order of what people spend on electronics for the boat. What becomes really problematic is if the bolts are found to be compromised to the point where they must be replaced. Given our location, I would contact Mars Metals if I ever got to this point. For people who do not live near a facility like this, it gets more tricky. I have limited experience installing bolts from the bottom of a keel and I could see it working in some instances but not all.

Thanks very much for expanding on that. Obviously it’s disappointing not to have a generally applicable risk reduction strategy. But then again, when did that every happen around boats!

The good thing is that I now understand the issues and how to reduce the risk to acceptable levels. One thing I would say is that I would need to think long and hard before buying a boat that say had tankage or mast step structure over the keel bolts since that can make the job of dropping the keel from, as you say, comparatively simple, to a much bigger job.

Hi John, thought I should address the keel questions for anyone considering a Beneteau cruiser and reading this. Cheeki Rafiki, was a Beneteau First designed primarily as a racer / cruiser. They have light hulls and rely on a structural liner for much of their hull rigidity, with bulkheads and “furniture” glued in. In the main, the boats are fit for purpose and they don’t have a history of losing their keels, even though there seems to be a serious question over the keel to hull design. I personally wouldn’t sail one offshore but would have no hesitation in owning one around the NZ coast, if I raced more.

The Beneteau Oceanis 473 was designed by Beneteau as their offshore model and as I have heard it told, the model was built to help alter their “bendy Beneteau” reputation. The Clipper Oceanis range (of which the 473 is one), are the last of the all hand laid fibreglass models before European regs changed to enforce epoxy, vacuum bagging and sandwich construction. The hulls were built super-thick of solid glass fibre and more so around the keels and other high stress areas. 473s then have massive supporting girders glassed into the bottom of the hull. The bulkheads are also glassed in not glued. The flanges of these girders are wide to improve the hull bonding and spread the keel load. Around the front and back of the keel area, the girders are only about 250 mm apart. The keel bolts go through both the girder flanges and the hull. Unlike the First, the 473 in particular has a much wider keel base and a double row of bolts (single row on the First). Comparing the two boats for offshore use, is like comparing a Toyota MR2 with a Toyota Land Cruiser – built for two very different things. My experience with owning a Beneteau is the QA processes were (are?) excellent, but I must add inspecting one or two bolts a year to my maintenance list. I haven’t so far because we run a dry bilge and the bolts are like new. And John, therein lies an opportunity for an astute buyer – there are gems in most production yacht manufacturer’s ranges, just as there are bad’uns. It is finding those good’uns that can pay off – the 473 is an absolute diamond. best regards Rob

Good to hear that the 473 has the bolts through the flanges and the grid glassed in. The key to the Cheeki Rafiki disaster is that she and her sisters had neither. Also, the report stated that other boats of her class had keel problems.

I wonder what Beneteau is doing these days with their newer boats.

Also it’s important to realize that Beneteau sold the class that Cheeki Rafiki was a member of as ocean capable. They make the same assertion for most of their current offerings.

Summary: any buyer needs to check to make sure the keel support structures are glassed in (not just glued) and that the bolts pass though the flanges, not just the hull skin. If they find this is not the case, run a mile.

And anyone considering buying any modern boat with a fin keel should read the Cheeki Rafiki report so at to know what to look for.

One more thought. Sorry to be such a pain in the ass on this. But one thing I have learned over the years running this site is that people skim (particularly the comments) not read carefully. They also tend the hear what they want to hear.

The point being that while I fully understand that you are not saying all Beneteaus have safe keels, just yours, I still need to jump in with the realities from the report.

Hi John, Why do sailboat keels smile? Because they are thinking about how much fun it would be to swim freely in the ocean like the dolphins, free of the heavy burden on their backs!

Of course we all know that GRP is forever. Even after you scrap the damn thing it’ll still be recognizable land fill or artificial reef for the next thousand years. Still there is one other material that deserve a passing derisive remark: Concrete. It’s a material used exclusively by amateur builders that never seems to survive the first owner.

Insurance company do not underwrite concrete boats in Canada. Not sure of USA. Since they need civil responsibility, place are limited for an owner. Altough it was a most decent material, well insulated, cheap, partially insulated.

Yes, we have friends with a concrete boat that has served them well. That said, I decided to leave the material out since good concrete boats are pretty rare.

For what it’s worth Joe Adams (the designer of our boat) had his first big success with the original Helsal that was a ferrocement boat. It smashed up records for the Sydney Hobart classic and was forever known as the ‘Flying Footpath’.

http://rolexsydneyhobart.com/news/2012/pre-race/helsal-tribute-to-joe-adams-in-rolex-sydney-hobart/

What a great name!

Ask any physicist about the stability of Aluminum alloy and they will say ; the aluminum stability derive from its oxyde layer which is the strongest material on earth after diamond. Thus any object built of aluminum alloy should make sure that oxyde layer is preserved. A simple piece of wood on an aluminum plate staying outside in the rain will get holed in a few months and will prove you that it can be attacked easily once the Al2O3 layer is depleted in oxygen poor environment. And aluminum is born of electricity and can be destroyed by electricity.

The ebook should have started with the french joke: Circumnavigators knows that 50 % of the boat going around the world have a metal hull, the remaining are US boats.

Each aluminum boat is a unique closed loop battery and had to be kept under cathodic state under all conditions. Some boat well builts have it naturally, some others don’t and with maintenance mistakes, this is were horror stories come from.

I am not found of polyester boats because the environnmental cost of getting rid of those tons of plastic polluants at the end of life have never been taken into consideration is the first price. Polyesther fiberglass is not recyclable. We are just pushing the problem forward to the next generations. One day not to far someone will wake up and put environnemental cost on the new GRP production boat and people will realise its not cheap.

Wood as said before, is only up to the maintenance made. My marina neighbor has a magnificient wood boat that he built himself, on the plan of Joshua. He told me last weekend, 6000 to built and 6000 hours to maintain since 30 years. A tribute to those brave men.

Steel… if only the genius of the french architects who recommended to build hulls in steel and the deck and infrastructure in stainless would have been more commonly communicated, we would have less steel boats relics today. 95 % of the paint maintenance of a steel boat is on the deck. A steel hull/stainless deck has about 1 hour of touch up maintenance every year (for all those logs and obstacles hit on the water)

Thus for metallic boats ultimately the material is not the problem, its the way it has been put together and maintained. A production aluminum sailboat could be the perfect boat for circumnavigators. For some specific usage, only steel can survive. This special boat is quite an achievement, almost 20 years in the polar sea: https://vagabond.fr/en/vagabond/

(Of course i am biased i have a year of mechanical engineering classes in material resistance and my full welding certification for both Aluminum alloys, Steel and 304 and 316 stainless on conventional SMAW and also on GMAW and GTAW.)

My experience over nearly 30 years is that the aluminium alloys used in boat building are a lot more durable than you indicate. For example my boat had teak decks and toe rails for the first 12 years of her life. And, despite the fact that water had got under the teak in many places and been there for years, we found only a little surface corrosion of no consequence when we removed the wood.

Yes, as I said in the article, it’s important to follow the rules with aluminium, but that’s far from rocket science and occasional mistakes do not result in a wrecked boat in a few weeks, as many will tell you.