No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

A Complete Guide to The Genoa Sail And How To Use It

The Genoa is massively used in sailing, usually teamed up by a mainsail. It’s a triangular sail attached to the forestay that’s easy to work with in any conditions, from light to moderate winds and beyond. I love my Genoa because it is so easy to handle, and when sailing on any point of sail with the wind behind the mast, it does a great job even without the mainsail set.

Today, I’ll explain what the Genoa sail actually is (many people actually mistake it for a Jib, but more on that later) what we use it for and how it actually works. I’ll also talk a bit about what materials they’re usually made of and teach you about the different parts.

To wrap things up, I’ll share some handy tips on how to keep your Genoa in tip-top shape to make it last as long as possible. For trust me, investing in a new one is an expensive affair that I can testify to!

What is a Genoa sail, and what do we use it for?

Let me begin with the basics, just in case you’re unfamiliar with sails. A Genoa is a headsail extending past and overlapping the mast. Genoas are typically larger than 115% of the foretriangle, with sizes varying between 120% and 150%.

This sail is often combined with a smaller main sail on masthead-rigged bluewater vessels but is also common on modern fractionally rigged vessels.

The Genoa is durable, versatile, and usable on all points of sail. There are better options for those who mainly sail upwind, like the Jib, but it is hard to beat for the extra canvas it provides when you turn around and sail downwind. As a result, the Genoa is standard on most modern sailing vessels and is truly a multi-purpose sail.

As I said in the beginning, it’s worth mentioning a common misunderstanding where the terms Genoa and Jib get mixed up. Many people call any headsail a Jib, which is a misinterpretation. I personally prefer to use the correct terminology to avoid any confusion, especially if you carry both on board. You can learn more about the Jib sail in this article.

Tip : If you want to use a simpler word for Genoa, “Genny” works well!

How the Genoa works on a sailboat

The Genoa provides a sail area forward of the mast , aiding in steering and balancing the boat effectively. It is usually flown together with the mainsail to catch the wind’s energy and push the boat forward, but it also works great on its own, especially when sailing any downwind angles.

The sail is curved, creating a pressure difference when exposed to the wind while sailing at closer angles than 90 degrees. The outer, rounded side (leeward side) has lower pressure than the inner, hollowed side (windward side).

This pressure difference creates lift, propelling the boat forward like how an airplane wing produces lift. On any lower angle than 90 degrees, the sail acts like a parachute to move the boat forward.

In simpler terms, I like to look at the Genoa as one of the boat’s main engines. You usually have a diesel engine onboard as well, but since it is a sailboat, you’d prefer to sail it, right?

How to rig a Genoa

The Genoa is rigged on either a furling system or directly to the forestay. Most modern sailing boats have a furling system, a long sleeve that runs from the top of the mast down to the bow and attaches to a drum on the bottom and a swivel on the top. The process for rigging a Genoa and a Jib is the same.

Let us take a look at the step-by-step process on how to rig the Genoa ready to sail onto a furling system:

- Feed the Genoa’s luff into the track on the furler’s sleeve with the top of the sail first and connect the head ring on the sail to the chackle on the swivel.

- Attach the Genoa halyard to the swivel and hoist the sail up.

- When the sail is hoisted almost all the way to the top, you attach the sail’s tack to a shackle on the top of the drum.

- Put the halyard on a winch and winch it tight.

- Now you have to manually roll up the sail around the forestay and tie on the two sheets to the clew of the sail.

- Lead the two sheets on each side of the vessel’s side decks through the sheet cars, turn blocks, and back to the winches .

- Now that the sail is furled away, we need to tie the furling line onto the drum. You have to figure out how the furling line attaches, as it differs from system to system.

- Once the furler line is attached to the drum, ensure that it can wrap itself up freely.

- Pull the sail back out using one of your sheets and monitor that the furling line wraps on nicely.

- Leed the furling line through the blocks and funnels, through the jammer , and leave it next to the winch.

- Furl the Genoa away again using the furling line and ensure that the sheets run freely as you monitor your sail getting wrapped nicely around the forestay.

- Secure the furler line jammer and tidy up your two sheets. Make sure to secure the sheets around the winches.

It is easy to understand why most sailing vessels use furling systems. I wouldn’t want to be without one. They make sail handling such a breeze! You can learn more about the sailboats standing rigging here.

How to use, reef, and trim a Genoa

To use the Genoa, you wrap the furler line around the winch , open the jammer, and pull on either of the sheets, depending on which tack you are sailing on.

You want to keep a hold on to the furler line to prevent the sail from unfurling itself uncontrollably, especially in strong winds.

You can now unfurl the entire sail or just a part of it. Adjust your car position and tighten the sheet once the whole sail, or the desired amount, is out.

How to furl and reef a Genoa

To furl or reef the Genoa, you do the opposite of unfurling it. Ease off the working sheet, but keep it on the winch. At the same time, pull in on the furler line either manually or on the winch.

Remember to move the cars forward and re-tighten the sheet if you are reefing away only a part of the sail. Reef earlier rather than later if the wind starts to pick up. More force in the sail only makes the task harder, and you risk overpowering your boat. Talk to any sailor and the first advice you’ll get is “reef often and reef early”.

When you’ve tried dipping your toe-rail underwater and had everything down below deck shuffled around in a mess, you’ll understand what I mean! (Yes, been there, done that…)

How to trim a Genoa

Adjusting the sheet cars and sheet tension is vital to obtaining an optimal sail shape in the Genoa. Finding this balance is what we call sail trim . We’re not going to dig too deep into sail trim in this article, but here is a rule of thumb:

You want the leech and foot of the sail to form an even “U” shape on any point of sail . When sailing upwind, you usually move the car aft. When bearing off the wind, you move the car forward.

The goal is to apply even tension on both the foot and the leech. When you reef the sail, you’ll also want to move the car forward to adjust for the reduced sail area. Sailing downwind doesn’t require the same fine-tuning as upwind sailing, making trimming easier. But keep an eye on the wind and reef before things get out of control!

Here are a few tips when sailing upwind:

- Winch up the Genoa sheet until the leech stops fluttering and the foot has a sweet, even “U” shape.

- You want to move the sheet car forward if the foot is tight and the leech flutters.

- Move the sheet cars aft if the leech is tight and the foot flutters.

- If the wind increases and the boat starts to heel excessively, you can either ease off the sheet or adjust your course more head to wind.

You should play around and experiment with sail trim, as every boat behaves differently. Trimming sails is an art that takes time to master. Staysails, Jibs, and Genoas are trimmed similarly, but the car positions will differ due to their size and shape differences. Once you learn how to trim a Genoa, you can trim any headail.

Sailing with more than one Genoa

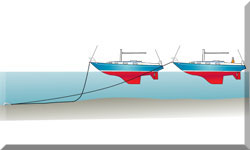

Navigating with multiple Genoa’s is great on extended downwind journeys. Most furling systems come with dual tracks, making it possible to fly two Genoa’s on a single furler, which again makes reefing a simple task. This arrangement can also be replicated or combined with Yankees and Jibs if you have several headsails onboard.

Certain boats are equipped with two or more forestays, allowing them to have two separately furled headsails. This configuration is often referred to as a cutter rig. Although most cutter rigs utilize a Staysail on the inner forestay and a Yankee sail on the outer, this flexible rig provides the liberty to explore a variety of setups.

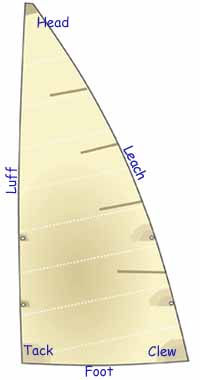

Exploring the different parts of the Genoa

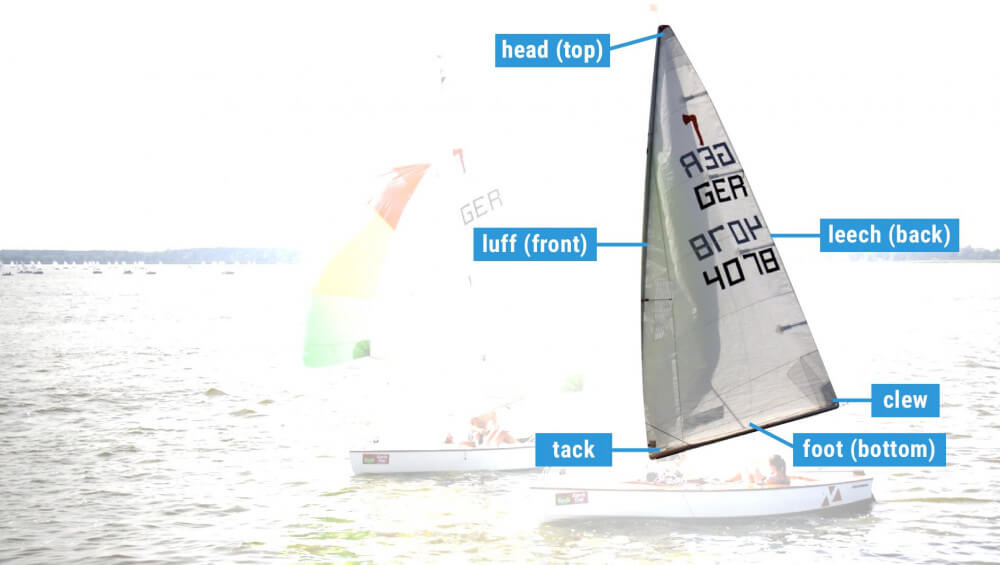

Head: The head is the top corner of the Genoa. It typically has a ring in the top corner that attaches to the Genoa halyard or the top swivel for furling systems.

Leech: The leech is the aft part of the sail, located between the clew and head.

Luff : A Genoa’s luff is the front part between the tack and head. Genoa’s are often equipped with luff foam to help maintain their shape when partially reefed on a furler.

Clew : The clew is the aft lower corner of the Genoa where the sheets are attached.

Tack : The tack is the lower, forward corner of the Genoa. The tack is connected to a furler drum on the forestay on most sailboats. Vessels using traditional hank-on headsails tie the tack to a fixed point on the bow.

Foot : The foot of the Genoa is the bottom portion of the sail between the clew and the tack.

Telltales: Telltales are small ropes, bands, or flags attached to the front of the Genoa’s leech to help us understand how the wind affects the sail and allow us to fine-tune the trim for optimal performance.

Commonly used materials for the Genoa

The most common material for Genoa’s today is Dacron woven polyester, closely followed by CDX laminate. Continuing up the price range, we find woven hybrids like Hydranet, Vectran, Radian, and other brands.

Next, we have more advanced laminates infused with exotic materials like aramids, carbon, and Kevlar. Peeking at the top of the line, we find the latest technology in DFi membrane sails like Elvstrøms EPEX or North Sails 3Di. These sails come at a premium price tag, though.

Modern technology has given us more economical alternatives to traditional Dacron sail fabric. Warp-oriented woven cloth is becoming popular due to its increased ability to keep shape over time without stretching to the same degree as traditionally cross-cut dacron sails.

ProRadial, made by Contender and Dimension Polyant, is a good example and is what I went for when I ordered a new Genoa and main for Ellidah.

North Sails has an excellent article that goes in-depth on sail materials.

The difference between a Genoa and a Jib sail

The difference between a Genoa and a Jib is that the Genoa is a headsail that extends past the mast and overlaps the mainsail, while the Jib is non-overlapping. The Jib is a smaller sail that is even easier to handle and works excellently when sailing close-hauled and pointing upwind.

The larger Genoa also works well upwind but excels on any points of sail with the wind behind the beam. The Genoa is usually between 120% and 150%, while the Jib is typically between 90% and 115% of the foretriangle size. Both of these sails can be used interchangeably on furling and traditional hank-on systems.

How to Maintain and Care for Your Genoa

Proper maintenance and care of your sails will ensure they operate at their best while minimizing wear and tear. They’ll keep their performance better, make your trip more enjoyable, and you can slap yourself on the shoulder in good consciousness, knowing that you’re taking good care of your equipment. It will save you money in the end, too, which is always nice .

Here are some guidelines on how to preserve and safeguard your Genoa:

- Regularly rinse the sail with fresh water and allow it to dry thoroughly before storing it. Ensuring it’s dry will fend off moisture and mildew accumulation.

- Annually service the sail. Inspect for any compromised seams and mend them as needed. If you spot any chafing marks, reinforce the sail with patches at chafe points and add chafe guards to the equipment it comes into contact with. Typically, the spreaders and shrouds

- Shield the sail from UV rays by storing it properly when not in use. A furling Genoa can be safeguarded by adding a UV strip to the foot and leech.

Check out this article to learn more about how to extend the lifespan of your sails.

Final words

Now that we have looked at the Genoa and its functions, you should pack your gear, set sail, and play around with it. Familiarize yourself with how the boat behaves on both tacks, and practice your reefing techniques.

I always stress the importance of reefing; if you don’t understand why now, you certainly will before you know it!

If you still have questions, check out the frequently asked questions section below or drop a comment in the comment field. I’ll be more than happy to answer any of your questions!

PS: Explore more sails in my easy guide to different types of sails here .

Exploring The Most Popular Types Of Sails On A Sailboat

FAQ – The Genoa Sail Explained

What is the foretriangle on a sailboat.

The foretriangle on a sailboat refers to the triangular area formed between the mast, forestay, and deck. This triangle is 100%. If you want to order a new headsail, you’ll have to measure and supply the sailmaker with these measurements.

What is the difference between Headsail, Jib, and Genoa?

A headsail or foresail is a generic term for any sail set before the mast. In other words, the Jib, Genoa, and Yankee are all what we call a headsail. Their difference lies in their respectable sizes, shapes, and utility on a sailing yacht.

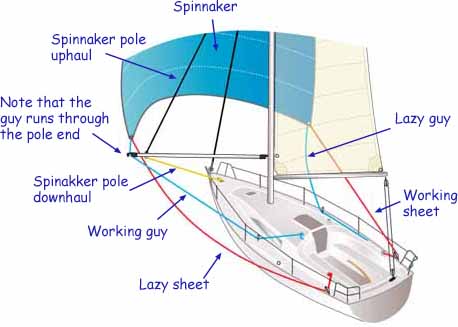

What is the difference between a Spinnaker and a Genoa?

The Spinnaker and Genoa are distinct types of sails used on sailboats, each serving different purposes and being suitable for various sailing conditions.

Here are the primary differences between them:

- A Genoa is designed to be used on all points of sail, while the Spinnaker is made to be used on deep angles between 120 and 180 degrees.

- The Genoa is relatively flat, while the Spinnaker is shaped more like a balloon and is used in light-wind conditions to capture as much wind as possible.

- The Spinnaker is much larger than a Genoa and is typically made in a thin nylon fabric. The Genoa, conversely, is made of sturdier materials, making it more durable in stronger wind.

- The Genoa is easier to handle and operate as the Spinnaker requires the use of a pole to extend its clew to the vessel’s side.

- While the Genoa can be reefed to adjust for different wind strengths, the Spinnaker is either fully set or fully taken down.

- The Spinnaker is excellent for downwind sailing in a breeze but can be a challenge to operate and take down when the wind increases.

- A Spinnaker usually looks better than a Genoa as it often comes in many beautiful color combinations.

The Spinnaker and the Genoa are both great sails. But as with other tools, they serve different purposes.

Why is a genoa sail called a genoa?

The name “Genoa” traces back to the Italian yachting hub of Genova. The Swedish sailor Sven Salén was the great uncle of The Ocean Race Managing Director Johan Salén. During the Coppa di Terreno race in 1926, Sven Salén modified an existing Jib to craft an overlapping Jib, now known as the Genoa sail.

His innovation proved successful as he scored a victory in the race. The sail then got named ‘Genoa’ as a tribute to the city where this historical sailing innovation was invented.

Is it OK to sail with just the Jib?

The Genoa is an excellent sail to fly by itself, especially on deep angles where the mainsail can block the wind. It also works on other points of sail on its own, but combining it with the mainsail will provide better balance in your boat and possibly prevent excessive weather helm. I often sail with just the Genoa when broad-reaching in moderate to strong wind.

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Anchoring & Mooring

- Boat Anatomy

- Boat Culture

- Boat Equipment

- Boat Safety

- Sailing Techniques

The Genoa Sail: A Guide

Genoa Sails are an essential addition to any sailboat’s gear. They provide extra sail area and power for improved boat performance and efficiency. This guide will help you learn about the different types of Genoa Sails, how to choose the perfect one for your sailboat, and tips for optimizing its performance and care.

Key Takeaways

- Genoa Sails are large headsails designed for light to moderate winds that produce lift and power for improved speed and performance.

- There are several types of Genoa Sails, ranging from the standard genoa to the roller furling genoa, each suitable for different applications.

- Larger sails offer more power but require more skill to handle while smaller sails are easier to manage.

- Dacron and laminated sailcloth are commonly used for making Genoa Sails, though materials like Kevlar and carbon fiber can also be employed.

- Careful handling of tacking and jibing should be observed in order to prevent luffing or loss of efficiency.

What is a Genoa Sail?

The Genoa Sail is a type of headsail larger than the jib and commonly used to sail in light to moderate winds. It’s characterized by its size and overlapping design, which allows it to catch more wind and gain greater power than smaller headsails.

Genoa Sails are ideal for cruising or long-distance sailing, as they provide better speed and performance while still being easy to handle.

One of the key advantages of the Genoa Sail is its ability to generate lift, pushing the boat forward and helping maintain velocity in light wind conditions. Its curved shape creates this lift, producing an airfoil effect, resulting in both push and drag.

The Genoa Sail permits greater control and maneuverability as it can be adjusted and trimmed accordingly. This makes it highly versatile, so it can be used on different occasions, from casual sailing to high-performance racing.

Types of Genoa Sail

There are several types of Genoa Sails, each with unique characteristics and advantages. The sail types include the standard genoa, the high clew genoa, the overlapping genoa, and the roller furling genoa.

The Standard Genoa

The Standard Genoa is the most typical type of Genoa Sail, designed for light to moderate winds and characterized by its moderate size with an overlapping design. This overlap typically ranges from 110% to 150%, enabling the sail to catch more wind and deliver more significant power than a smaller jib yet still be gentle enough to manage.

The Standard Genoa is highly versatile, suitable for up and downwind sailing and in different wind conditions, from light to moderate. Its ease of control also makes it great for sailors of various skill levels.

To ensure optimal performance, however, proper trimming and adjustment must be made; this entails adjusting the angle of the sail to the wind, controlling the tension on the halyard lines and sheets, and making adjustments to the leech and foot.

When done correctly, this can lead to excellent speed and performance, which is why it’s such a helpful sail in any sailor’s toolkit.

The High Clew Genoa

Featuring a higher clew than the Standard Genoa, the High Clew Genoa offers better control and maneuverability and improved visibility from the cockpit. It’s beneficial in light wind as it catches more wind and produces more power.

To reach optimal performance, however, some adjustments to the sail’s rigging and trim have to be done; this includes ensuring the halyard and sheets are properly tensioned for better sail shape and angle of attack.

Despite these requirements, the High Clew Genoa is still straightforward to handle, making it suitable for sailors of any skill level. With its improved performance in lighter winds, this type of Genoa Sail can be a great addition to any sailor’s toolkit, particularly those who often go on cruising or long-distance sailing trips.

The Overlapping Genoa

The Overlapping Genoa is a larger and more powerful version of the Standard Genoa, with an overlap between the sail and mast that ranges from 110% to 150%. This design allows for enhanced lift and power, perfect for racing and high-performance sailing.

With this kind of sail comes a higher level of difficulty in controlling it in more intense winds, so it is better suited for experienced sailors.

Despite its challenges, the Overlapping Genoa remains popular among those looking to get maximum speed and performance from their vessel. Its increased size and power can provide a significant boost in racing scenarios in which every second counts, and experienced sailors push their limits.

For optimal results, however, proper trimming and adjustment are essential; this includes ensuring the sail’s angle to the wind, halyard tension, and sheet tension are all correctly balanced for a practical shape without supporting too much power or getting damaged.

The Roller Furling Genoa

The Roller Furling Genoa is designed to be easily rolled and stored when not in use, making it convenient and easy to deploy or stow. It’s a popular choice for cruising and recreational sailing due to its simple handling and decreased need for physical labor.

However, its design also limits its performance capabilities compared to other types of Genoa Sails; it can get overpowered in high winds, reducing power and efficiency. As such, this sail is not generally used for racing or high-performance sailing, as these scenarios require maximal speed and performance.

Despite these drawbacks, the Roller Furling Genoa retains popularity among sailors who appreciate its ease of use. However, sailors must take good care of the sail with proper maintenance and consider its limitations when planning their sailing trips.

Genoa Sail Sizes

The size of a Genoa Sail is defined by its relationship to the boat’s foretriangle, which is the triangle between the mast, forestay, and deck. The sail typically ranges from 110% to 150% of the foretriangle, with greater overlap increasing power and lift.

The size of a Genoa Sail can, therefore, significantly affect the boat’s performance and handling. A larger sail can give more power and lift, making it suitable for racing and high-performance sailing; however, this comes at the cost of needing more experience for proper handling, particularly in high winds.

In contrast, smaller sails are easier to control and manage, making them ideal for cruising and recreational sailing; plus, they prove more efficient in higher winds as it generates less drag and won’t overpower the boat.

When deciding on a sail size, it’s essential to examine your boat , including its size, design and intended use. Larger sails may be necessary for race or high-performance scenarios but can be too challenging to manage while traveling; conversely, smaller sails may be better suited for cruising yet could lack enough power or lift when going all out.

Genoa Sail Construction

Dacron is a commonly used material for Genoa Sails as it is durable, easy to handle, and affordable, making it ideal for cruising and recreational sailing.

For more performance-oriented use, such as racing or high-performance sailing, laminated sailcloth (a combination of multiple synthetic fibers with an adhesive) is often employed. It’s lightweight and has higher performance characteristics though special care may be required.

Advanced materials that have been gaining traction in the field are Kevlar and carbon fiber; they provide remarkable strength and durability, which makes them perfect for intense situations, but they cost a lot more money than conventional materials.

Today’s sails employ advanced techniques like radial or tri-radial panels, helping to distribute loads evenly across the sail and heighten performance even further.

Handling Genoa Sails

Proper trimming of the Genoa Sail is essential for creating lift and power and preventing stalling or inefficiency. This involves adjusting the halyard tension to obtain the right sail shape and ensuring that the sheets are correctly tensioned to control the angle of the sail relative to the wind. To adjust the angle of the sail relative to the boat, sailors can move the sheets in or out or change the position of cars or tracks.

Reefing is used when there are high winds, whereby reducing sail size prevents overpowering. This is usually done by partially furling it around the forestay or removing part of it with reefing lines. The reduction depends on wind conditions and boat size; typically, 20-30% should be reduced to maintain control and stability while avoiding damage to rigging and sails.

Once reefing has been done, it’s essential to ensure proper trimming afterward to optimize performance. This includes adjusting halyard tension, sheets, and angle of attack accordingly to achieve an optimal level of sail shape relative to the wind .

Finally, tacking and jibing involve turning through wind direction to change course – these maneuvers must be carefully handled so that luffing or loss of efficiency does not occur.

Difference between Genoas and other sail types

Jibs are an alternative to Genoa Sails, typically used in higher wind conditions and hanked onto the forestay instead of roller-furled. They are smaller than Genoa Sails and generate lift and power as effectively.

Code Zero sails can generate lift and power for light wind conditions, even with very little wind. These sails are larger than Genoa Sails and have a unique shape, making them ideal for racing and high-performance sailing.

Finally, spinnakers are downwind sails designed to capture the wind from behind the boat. These are usually much larger than Genoa Sails, making them perfect for racing or high-performance sailing where speed and efficiency matter.

Genoa Trim and Performance

Maximizing performance for a Genoa Sail involves adjusting the sail’s angle to the wind to achieve the best possible sail shape and angle of attack. This can be accomplished by adjusting the sheets, halyard tension, and sail angle relative to the boat. Proper trimming is essential for creating lift and power while preventing stalling or loss of efficiency.

Optimizing sail shape is another helpful tip for maximizing Genoa Sail performance. This can be done by adjusting the tension and position of the sail to get the right amount of shape and angle relative to the wind. Achieving proper sail shape is crucial for generating lift and power and preventing stalling or loss of efficiency.

Adjusting where necessary, twist is also essential in improving Genoa Sail performance. Twist refers to the difference between the top and bottom angles of the sail, influencing efficiency and power levels. By tinkering with twist, one can optimize their sails performance while generating more lift and power.

Finally, proper maintenance should not be overlooked when it comes to achieving peak performance from a Genoa Sail, and regularly inspecting for damage or wear, cleaning/drying after use, and storing correctly when not in use are all critical steps toward ensuring optimal functioning now and into the future.

Genoa Sails are an invaluable and essential part of any sailboat’s inventory, significantly impacting the performance and efficiency of the vessel. Different types of Genoa Sails exist, each with distinct characteristics and purposes for particular sailing environments. Consequently, selecting the correct sail for your specific needs is essential.

When choosing a Genoa Sail, factors such as use, size, fabric type, and construction quality should all be considered. Additionally, proper maintenance and care of your sail are paramount if you want to reap its full potential over the long term.

Maximizing your Genoa Sail performance can be achieved by adequately adjusting the angle and shape of the sail, optimizing twist when necessary, and consistently maintaining good practice with regard to upkeep.

Genoa Sail FAQs

Q: What is a Genoa Sail, and what is it used for?

A: A Genoa Sail is a large triangular sail deployed on a sailboat’s head stay. It provides additional sail area and power, ideal for light to moderate wind conditions. It is commonly used for cruising, racing, and offshore sailing.

Q: What are the different types of Genoa Sails?

A: Different types of Genoa Sails include standard Genoas, high clew Genoas, overlapping Genoas, and roller furling Genoas.

Q: How do I choose the right size Genoa Sail for my boat?

A: The size of the Genoa Sail depends on several factors, such as the type and size of the boat, sailing conditions, and personal preferences. Selecting an appropriately sized sail to maximize performance and safety on the water is essential.

Q: How do I trim a Genoa Sail for optimal performance?

A: Trimming a Genoa Sail requires adjusting its angle to the wind to achieve the best possible sail shape and angle of attack. This can be accomplished by manipulating its sheets, halyard tension, and angle relative to the boat. Proper trimming allows lift and power generation while preventing stalling or loss of efficiency.

Q: How do I maintain and care for my Genoa Sail?

A: Effective maintenance for a Genoa Sail entails regular inspection, cleaning (after use), storage (when not being used), as well as paying attention to age/condition. Inspecting your sail regularly for any damage or wear; cleaning it after each use; storing it safely when not in use; replacing it if necessary to attain peak performance with optimum safety standards.

Q: How do Genoa Sails differ from other types of sails?

A: In comparison with other types of sails such as jibs, code zeros, or spinnakers, differences between them include size (Genoas are larger), shape (Genoas are more triangularly shaped) as, well as intended use (light-moderate winds).

Flemishing a Line: What is it?

Cleat hitch knot: a boater’s guide, related posts, whisker pole sailing rig: techniques and tips, reefing a sail: a comprehensive guide, sail trim: speed, stability, and performance, cleat hitch knot: a boater's guide.

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Statement

© 2023 TIGERLILY GROUP LTD, 27 Old Gloucester Street, London, WC1N 3AX, UK. Registered Company in England & Wales. Company No. 14743614

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Add New Playlist

- Select Visibility - Public Private

Better Sailing

Jib Vs Genoa: What is the Difference?

Most modern sailboats don’t need big overlapping headsails to ensure performance when sailing upwind. In the old days, sailboats were really heavy, their keels were long, and the sail area was the most crucial part that made the boat moving. However, nowadays light masts and rigging are available and facilitate many things while sailing. For example, if you increase the mast’s height and apply a high-aspect sail plan with a jib that overlaps no more than 105%, well this is quite an efficient rigging. So, are you are thinking of going offshore and wondering what sails are the best for your sailboat? Do you want to clarify the difference between a jib and a genoa? Then, follow me and keep reading!

Description of a Genoa

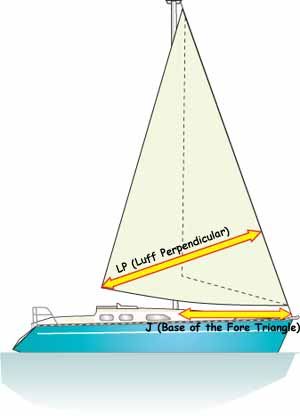

The main characteristics of a genoa are its shape and size. Genoas go past the mast, are triangular, and tend to overlap the mainsail, to some extent. It’s also one of the many headsails that can be set on a Bermudian rig. The numbers 130,150 etc refer to a percentage that has to do about the relationship of the length of the foot of the genoa and from the forestay to the front of the mast. As a result of this operation, i.e. the Luff Perpendicular divided by J (the distance), you get the overlap percentage of the sail.

Keep in mind that the larger the number you get the larger the sail would be. In general, in order to measure genoas, we often use the length of their Luff Perpendicular. In order to construct the LP, you can draw a line from the sail’s clew to the luff, and carefully intersect the luff at the right angle.

Description of a Jib

The Jib is also a triangular sail that increases sail area and improves handling. Therefore, it increases the sailboat’s speed. Basically, the mainsail controls the stern of the ship whereas the headsail, which sits forward the mast, is most of the time a jib. One of the main functions of the Jib is that it funnels the airflow along the front of the mainsail. This improves the airflow. Moreover, the jib gives control over the bow of the boat, thus making it easier to maneuver the boat. There are different sizes for a jib with the smallest being a storm jib.

In case the boat has a furler, then the size of the genoa or jib can be adjusted according to the wind’s strength, direction, and speed. Usually, jibs are 100% to 115% LP and are used in areas with strong winds. Also, a jib won’t be longer than 115% LP of the fore-triangle dimensions. Lastly, to ensure better performance in high wind speed the smaller area of the jib the better.

>>Also Read: Names of Sails on a Sailboat

Genoa VS Jibs – What Is The Difference Between Them?

Generally, Jibs and Genoas are triangular sails that are attached to a stay in front of the mast. Jibs and genoas are employed in tandem with the mainsail in order to stabilize the sailboat. They usually run from the head of the foremast to the bowsprit. A genoa is like a jib but is larger and reaches past the mast. But, as aforementioned, when the jib overlaps the mast we refer to it as a genoa. Also, a genoa overlaps the mainsail to some degree. Both sails are measured by their Luff Perpendicular percentage, i.e. the area within the fore-triangle that they use. Sometimes, there are large genoas that cover the majority of the mainsail. This mainly happens in light wind conditions where the most sail area is used to increase performance.

And again, when the headsail doesn’t overlap the mast is considered a jib. On the other hand, an overlapping sail is a genoa. Generally, smaller jibs are more lightweight, less expensive, and easy to handle. Jibs might also have a better lifespan as their leeches aren’t dragged across the mast, shrouds, and spreaders. So, all these characteristics make the jibs easier to trim and change. Furthermore, as they weigh less they will heel and pitch less. Lastly, keep in mind that there are different sailcloths weights, and materials that can be used on jibs and genoas. The sail design of each sail is always based on the type of sailboat and the sailing conditions will determine the sailcloth’s weight.

Having Multiple or Less Sails on your Sailboat

In case your sailboat has a larger genoa then you ought to think about getting a smaller headsail. For example, a sail with an LP of around 115% or maybe less. You can use the smaller sail when the wind is getting stronger and keep your genoa in storage. It’s essential to store, protect, and generally take care of your sails a few times per year. So, it’s recommended to often change your sails once in a while. Remember that for every boat has its own sail plan. For example, a boat might need one, two sails, three, etc that will enhance its performance. Each one used for different weather conditions and for different sailing plans.

The rule of thumb says that the fewer the sails less the drag will be. Meaning that you can sail higher to the wind with a single sail rather than having multiple sails of the same aspect ratio and total area. Furthermore, for the same total sail area and same geometrical shape, having multiple sails means that they’ll be less tall. In other words, they’ll catch slower wind closer to the ground. However, for the same total sail area, multiple sails will provide less heeling. This means that you can have lighter structures that support them.

Sail Area and Furling

In the old times, boats used to have long and shallow keels therefore it was crucial to fly a significant amount of sail in order to produce horsepower. But, when a vessel has a light material construction, light masts, and rigging then the height of the mast can be taller without having an effect on the righting moment. So, an overlapping jib, around 115%, results in more efficiency and less dependence on the additional overlap. But, when furling away sail shape from a large genoa you might reduce the sail’s shape efficiency. This is because when using a genoa for strong winds, it’s going to gradually cause an uneven stretch to the Dacron.

Remember that not all sails suit for all kinds of boats. Some boat owners might recommend a specific sail for a specific vessel. But the most important factors that determine what sails suit your boat are the location in which you sail, the type of the vessel, and the captain’s experience. For example, a sail made for Oceanis 331 in Florida will be completely different than a sail made for the same boat that sails in the Meditteranean.

But, what is the best sail size for cruising boats? A 130 or 135% headsail is great because this sail shape is flat thus can be reefed efficiently. However, a 130% headsail doesn’t have a good sheeting angle but is great for offshore sailing. On the other hand, non-overlapping headsails have a narrow sheeting angle so they’re not appropriate for offshore sailing.

In general, light-air sails are large sails and need adequate camber depth to work in light winds. So, when rolling them up and use them reefed you can’t take in enough of the camber to make the sail work windward. And that’s why there are several roller-furling headsails that include lengths of rope or a strip of dense foam that runs along the luff of the sail from the head to the tack.

Apart from that, any sailboat traveling offshore is going to need a small 130% headsail in order to withstand harsh weather conditions. It’s always better to use more than one headsail when voyaging overseas. Last but not least, don’t forget to take into consideration the trade-offs when sailing upwind.

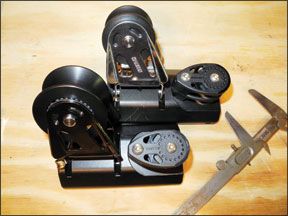

Improve your Sailboat’s Performance

As aforementioned, remember that the most crucial factors that determine the right sail size for your sailboat are the type of your vessel and the kind of passage you’re planning. There are certain things that you can do to improve your sails’ performance, no matter the kind of headsail you have. The first one refers to adding a means of adjusting the sheeting position when reefing and unreefing the headsail. For instance, you can add a block-and-tackle system that can pull the genoa lead forward when the sail is reefed. And when unreefed you can ease it aft. Generally, when moving a lead forward or aft, this changes the angle at which the sheet pulls down on the clew. And when pulling the clew down it trims the top of the jib, but when moving it aft it opens the top of the jib.

The Bottom Line

Modern technology and sail engineering have improved the development of sailcloths, sails’ versatility, and design tools to enhance their performance. Nowadays, you can choose between different types of sails according to the type of your sailboat, location, and experience. So, what’s the difference between a jib and a genoa? In order to clarify the main difference between a jib and genoa you should bear this in mind: When the foot of the headsail is longer than the distance from the forestay to the mast then we refer to a Genoa. Otherwise, the headsail is called a Jib. Basically, a genoa is a large jib that reaches past the mast and overlaps the mainsail. I hope that by reading this article you made clear the difference between a jib and a genoa and how you can enhance your sails’ performance. Wish you a lot of adventurous voyages to come!

Peter is the editor of Better Sailing. He has sailed for countless hours and has maintained his own boats and sailboats for years. After years of trial and error, he decided to start this website to share the knowledge.

Related Posts

Lagoon Catamaran Review: Are Lagoon Catamarans Good?

Best Inboard Boat Engine Brands

Are O’Day Sailboats Good? A Closer Look at a Classic Brand

Why Do Sailboats Lean?

- Buyer's Guide

- Destinations

- Maintenance

- Sailing Info

Hit enter to search or ESC to close.

The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

What's that sail for? Generally, I don't know. So I've come up with a system. I'll explain you everything there is to know about sails and rigs in this article.

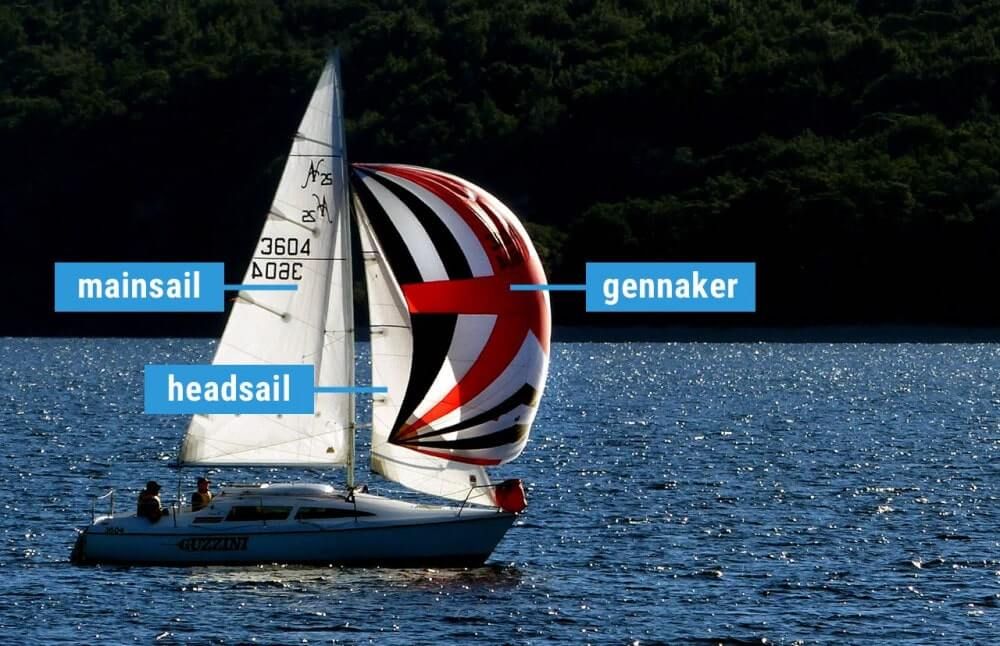

What are the different types of sails? Most sailboats have one mainsail and one headsail. Typically, the mainsail is a fore-and-aft bermuda rig (triangular shaped). A jib or genoa is used for the headsail. Most sailors use additional sails for different conditions: the spinnaker (a common downwind sail), gennaker, code zero (for upwind use), and stormsail.

Each sail has its own use. Want to go downwind fast? Use a spinnaker. But you can't just raise any sail and go for it. It's important to understand when (and how) to use each sail. Your rigging also impacts what sails you can use.

On this page:

Different sail types, the sail plan of a bermuda sloop, mainsail designs, headsail options, specialty sails, complete overview of sail uses, mast configurations and rig types.

This article is part 1 of my series on sails and rig types. Part 2 is all about the different types of rigging. If you want to learn to identify every boat you see quickly, make sure to read it. It really explains the different sail plans and types of rigging clearly.

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types (with Pictures)

First I'll give you a quick and dirty overview of sails in this list below. Then, I'll walk you through the details of each sail type, and the sail plan, which is the godfather of sail type selection so to speak.

Click here if you just want to scroll through a bunch of pictures .

Here's a list of different models of sails: (Don't worry if you don't yet understand some of the words, I'll explain all of them in a bit)

- Jib - triangular staysail

- Genoa - large jib that overlaps the mainsail

- Spinnaker - large balloon-shaped downwind sail for light airs

- Gennaker - crossover between a Genoa and Spinnaker

- Code Zero or Screecher - upwind spinnaker

- Drifter or reacher - a large, powerful, hanked on genoa, but made from lightweight fabric

- Windseeker - tall, narrow, high-clewed, and lightweight jib

- Trysail - smaller front-and-aft mainsail for heavy weather

- Storm jib - small jib for heavy weather

I have a big table below that explains the sail types and uses in detail .

I know, I know ... this list is kind of messy, so to understand each sail, let's place them in a system.

The first important distinction between sail types is the placement . The mainsail is placed aft of the mast, which simply means behind. The headsail is in front of the mast.

Generally, we have three sorts of sails on our boat:

- Mainsail: The large sail behind the mast which is attached to the mast and boom

- Headsail: The small sail in front of the mast, attached to the mast and forestay (ie. jib or genoa)

- Specialty sails: Any special utility sails, like spinnakers - large, balloon-shaped sails for downwind use

The second important distinction we need to make is the functionality . Specialty sails (just a name I came up with) each have different functionalities and are used for very specific conditions. So they're not always up, but most sailors carry one or more of these sails.

They are mostly attached in front of the headsail, or used as a headsail replacement.

The specialty sails can be divided into three different categories:

- downwind sails - like a spinnaker

- light air or reacher sails - like a code zero

- storm sails

The parts of any sail

Whether large or small, each sail consists roughly of the same elements. For clarity's sake I've took an image of a sail from the world wide webs and added the different part names to it:

- Head: Top of the sail

- Tack: Lower front corner of the sail

- Foot: Bottom of the sail

- Luff: Forward edge of the sail

- Leech: Back edge of the sail

- Clew: Bottom back corner of the sail

So now we speak the same language, let's dive into the real nitty gritty.

Basic sail shapes

Roughly speaking, there are actually just two sail shapes, so that's easy enough. You get to choose from:

- square rigged sails

- fore-and-aft rigged sails

I would definitely recommend fore-and-aft rigged sails. Square shaped sails are pretty outdated. The fore-and-aft rig offers unbeatable maneuverability, so that's what most sailing yachts use nowadays.

Square sails were used on Viking longships and are good at sailing downwind. They run from side to side. However, they're pretty useless upwind.

A fore-and-aft sail runs from the front of the mast to the stern. Fore-and-aft literally means 'in front and behind'. Boats with fore-and-aft rigged sails are better at sailing upwind and maneuvering in general. This type of sail was first used on Arabic boats.

As a beginner sailor I confuse the type of sail with rigging all the time. But I should cut myself some slack, because the rigging and sails on a boat are very closely related. They are all part of the sail plan .

A sail plan is made up of:

- Mast configuration - refers to the number of masts and where they are placed

- Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality

- Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat

There are dozens of sails and hundreds of possible configurations (or sail plans).

For example, depending on your mast configuration, you can have extra headsails (which then are called staysails).

The shape of the sails depends on the rigging, so they overlap a bit. To keep it simple I'll first go over the different sail types based on the most common rig. I'll go over the other rig types later in the article.

Bermuda Sloop: the most common rig

Most modern small and mid-sized sailboats have a Bermuda sloop configuration . The sloop is one-masted and has two sails, which are front-and-aft rigged. This type of rig is also called a Marconi Rig. The Bermuda rig uses a triangular sail, with just one side of the sail attached to the mast.

The mainsail is in use most of the time. It can be reefed down, making it smaller depending on the wind conditions. It can be reefed down completely, which is more common in heavy weather. (If you didn't know already: reefing is skipper terms for rolling or folding down a sail.)

In very strong winds (above 30 knots), most sailors only use the headsail or switch to a trysail.

The headsail powers your bow, the mainsail powers your stern (rear). By having two sails, you can steer by using only your sails (in theory - it requires experience). In any case, two sails gives you better handling than one, but is still easy to operate.

Let's get to the actual sails. The mainsail is attached behind the mast and to the boom, running to the stern. There are multiple designs, but they actually don't differ that much. So the following list is a bit boring. Feel free to skip it or quickly glance over it.

- Square Top racing mainsail - has a high performance profile thanks to the square top, optional reef points

- Racing mainsail - made for speed, optional reef points

- Cruising mainsail - low-maintenance, easy to use, made to last. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Full-Batten Cruising mainsail - cruising mainsail with better shape control. Eliminates flogging. Full-length battens means the sail is reinforced over the entire length. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- High Roach mainsail - crossover between square top racing and cruising mainsail, used mostly on cats and multihulls. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Mast Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the mast - very convenient but less control; of sail shape. Have no reef points

- Boom Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the boom. Have no reef points.

The headsail is the front sail in a front-and-aft rig. The sail is fixed on a stay (rope, wire or rod) which runs forward to the deck or bowsprit. It's almost always triangular (Dutch fishermen are known to use rectangular headsail). A triangular headsail is also called a jib .

Headsails can be attached in two ways:

- using roller furlings - the sail rolls around the headstay

- hank on - fixed attachment

Types of jibs:

Typically a sloop carries a regular jib as its headsail. It can also use a genoa.

- A jib is a triangular staysail set in front of the mast. It's the same size as the fore-triangle.

- A genoa is a large jib that overlaps the mainsail.

What's the purpose of a jib sail? A jib is used to improve handling and to increase sail area on a sailboat. This helps to increase speed. The jib gives control over the bow (front) of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship. The jib is the headsail (frontsail) on a front-and-aft rig.

The size of the jib is generally indicated by a number - J1, 2, 3, and so on. The number tells us the attachment point. The order of attachment points may differ per sailmaker, so sometimes J1 is the largest jib (on the longest stay) and sometimes it's the smallest (on the shortest stay). Typically the J1 jib is the largest - and the J3 jib the smallest.

Most jibs are roller furling jibs: this means they are attached to a stay and can be reefed down single-handedly. If you have a roller furling you can reef down the jib to all three positions and don't need to carry different sizes.

Originally called the 'overlapping jib', the leech of the genoa extends aft of the mast. This increases speed in light and moderate winds. A genoa is larger than the total size of the fore-triangle. How large exactly is indicated by a percentage.

- A number 1 genoa is typically 155% (it used to be 180%)

- A number 2 genoa is typically 125-140%

Genoas are typically made from 1.5US/oz polyester spinnaker cloth, or very light laminate.

This is where it gets pretty interesting. You can use all kinds of sails to increase speed, handling, and performance for different weather conditions.

Some rules of thumb:

- Large sails are typically good for downwind use, small sails are good for upwind use.

- Large sails are good for weak winds (light air), small sails are good for strong winds (storms).

Downwind sails

Thanks to the front-and-aft rig sailboats are easier to maneuver, but they catch less wind as well. Downwind sails are used to offset this by using a large sail surface, pulling a sailboat downwind. They can be hanked on when needed and are typically balloon shaped.

Here are the most common downwind sails:

- Big gennaker

- Small gennaker

A free-flying sail that fills up with air, giving it a balloon shape. Spinnakers are generally colorful, which is why they look like kites. This downwind sail has the largest sail area, and it's capable of moving a boat with very light wind. They are amazing to use on trade wind routes, where they can help you make quick progress.

Spinnakers require special rigging. You need a special pole and track on your mast. You attach the sail at three points: in the mast head using a halyard, on a pole, and on a sheet.

The spinnaker is symmetrical, meaning the luff is as long as its leech. It's designed for broad reaching.

Gennaker or cruising spinnaker

The Gennaker is a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker. It has less downwind performance than the spinnaker. It is a bit smaller, making it slower, but also easier to handle - while it remains very capable. The cruising spinnaker is designed for broad reaching.

The gennaker is a smaller, asymmetric spinnaker that's doesn't require a pole or track on the mast. Like the spinnaker, and unlike the genoa, the gennaker is set flying. Asymmetric means its luff is longer than its leech.

You can get big and small gennakers (roughly 75% and 50% the size of a true spinnaker).

Also called ...

- the cruising spinnaker

- cruising chute

- pole-less spinnaker

- SpinDrifter

... it's all the same sail.

Light air sails

There's a bit of overlap between the downwind sails and light air sails. Downwind sails can be used as light air sails, but not all light air sails can be used downwind.

Here are the most common light air sails:

- Spinnaker and gennaker

Drifter reacher

Code zero reacher.

A drifter (also called a reacher) is a lightweight, larger genoa for use in light winds. It's roughly 150-170% the size of a genoa. It's made from very lightweight laminated spinnaker fabric (1.5US/oz).

Thanks to the extra sail area the sail offers better downwind performance than a genoa. It's generally made from lightweight nylon. Thanks to it's genoa characteristics the sail is easier to use than a cruising spinnaker.

The code zero reacher is officially a type of spinnaker, but it looks a lot like a large genoa. And that's exactly what it is: a hybrid cross between the genoa and the asymmetrical spinnaker (gennaker). The code zero however is designed for close reaching, making it much flatter than the spinnaker. It's about twice the size of a non-overlapping jib.

A windseeker is a small, free-flying staysail for super light air. It's tall and thin. It's freestanding, so it's not attached to the headstay. The tack attaches to a deck pad-eye. Use your spinnakers' halyard to raise it and tension the luff.

It's made from nylon or polyester spinnaker cloth (0.75 to 1.5US/oz).

It's designed to guide light air onto the lee side of the main sail, ensuring a more even, smooth flow of air.

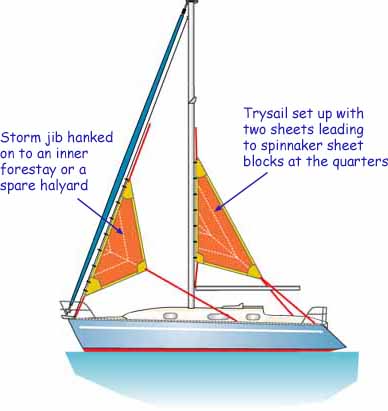

Stormsails are stronger than regular sails, and are designed to handle winds of over 45 knots. You carry them to spare the mainsail. Sails

A storm jib is a small triangular staysail for use in heavy weather. If you participate in offshore racing you need a mandatory orange storm jib. It's part of ISAF's requirements.

A trysail is a storm replacement for the mainsail. It's small, triangular, and it uses a permanently attached pennant. This allows it to be set above the gooseneck. It's recommended to have a separate track on your mast for it - you don't want to fiddle around when you actually really need it to be raised ... now.

| Sail | Type | Shape | Wind speed | Size | Wind angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bermuda | mainsail | triangular, high sail | < 30 kts | ||

| Jib | headsail | small triangular foresail | < 45 kts | 100% of foretriangle | |

| Genoa | headsail | jib that overlaps mainsail | < 30 kts | 125-155% of foretriangle | |

| Spinnaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-15 kts | 200% or more of mainsail | 90°–180° |

| Gennaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-20 kts | 85% of spinnaker | 75°-165° |

| Code Zero or screecher | light air & upwind | tight luffed, upwind spinnaker | 1-16 kts | 70-75% of spinnaker | |

| Storm Trysail | mainsail | small triangular mainsail replacement | > 45 kts | 17.5% of mainsail | |

| Drifter reacher | light air | large, light-weight genoa | 1-15 kts | 150-170% of genoa | 30°-90° |

| Windseeker | light air | free-flying staysail | 0-6 kts | 85-100% of foretriangle | |

| Storm jib | strong wind headsail | low triangular staysail | > 45 kts | < 65% height foretriangle |

Why Use Different Sails At All?

You could just get the largest furling genoa and use it on all positions. So why would you actually use different types of sails?

The main answer to that is efficiency . Some situations require other characteristics.

Having a deeply reefed genoa isn't as efficient as having a small J3. The reef creates too much draft in the sail, which increases heeling. A reefed down mainsail in strong winds also increases heeling. So having dedicated (storm) sails is probably a good thing, especially if you're planning more demanding passages or crossings.

But it's not just strong winds, but also light winds that can cause problems. Heavy sails will just flap around like laundry in very light air. So you need more lightweight fabrics to get you moving.

What Are Sails Made Of?

The most used materials for sails nowadays are:

- Dacron - woven polyester

- woven nylon

- laminated fabrics - increasingly popular

Sails used to be made of linen. As you can imagine, this is terrible material on open seas. Sails were rotting due to UV and saltwater. In the 19th century linen was replaced by cotton.

It was only in the 20th century that sails were made from synthetic fibers, which were much stronger and durable. Up until the 1980s most sails were made from Dacron. Nowadays, laminates using yellow aramids, Black Technora, carbon fiber and Spectra yarns are more and more used.

Laminates are as strong as Dacron, but a lot lighter - which matters with sails weighing up to 100 kg (220 pounds).

By the way: we think that Viking sails were made from wool and leather, which is quite impressive if you ask me.

In this section of the article I give you a quick and dirty summary of different sail plans or rig types which will help you to identify boats quickly. But if you want to really understand it clearly, I really recommend you read part 2 of this series, which is all about different rig types.

You can't simply count the number of masts to identify rig type But you can identify any rig type if you know what to look for. We've created an entire system for recognizing rig types. Let us walk you through it. Read all about sail rig types

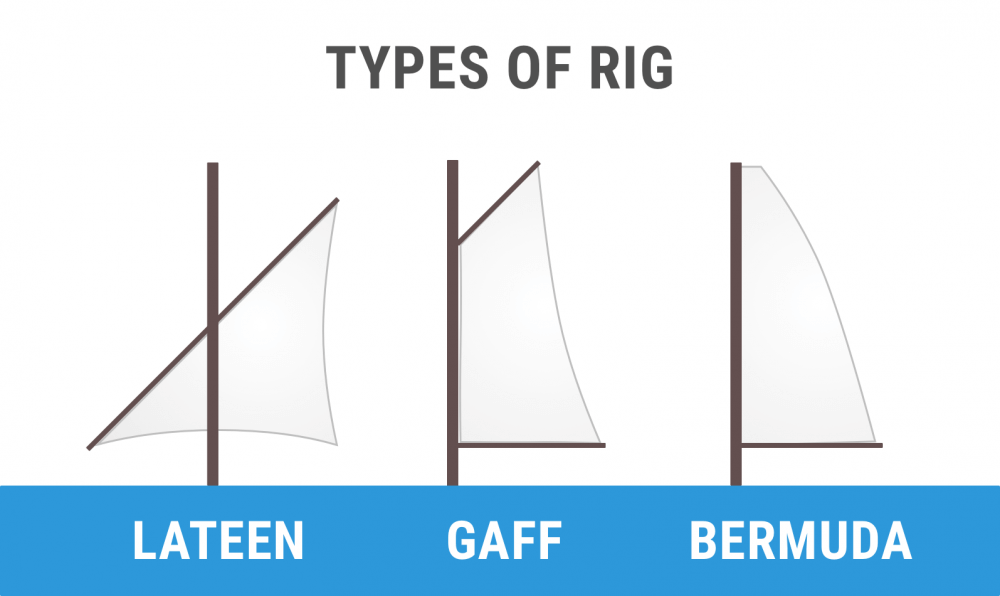

As I've said earlier, there are two major rig types: square rigged and fore-and-aft. We can divide the fore-and-aft rigs into three groups:

- Bermuda rig (we have talked about this one the whole time) - has a three-sided mainsail

- Gaff rig - has a four-sided mainsail, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff

- Lateen rig - has a three-sided mainsail on a long yard

There are roughly four types of boats:

- one masted boats - sloop, cutter

- two masted boats - ketch, schooner, brig

- three masted - barque

- fully rigged or ship rigged - tall ship

Everything with four masts is called a (tall) ship. I think it's outside the scope of this article, but I have written a comprehensive guide to rigging. I'll leave the three and four-masted rigs for now. If you want to know more, I encourage you to read part 2 of this series.

One-masted rigs

Boats with one mast can have either one sail, two sails, or three or more sails.

The 3 most common one-masted rigs are:

- Cat - one mast, one sail

- Sloop - one mast, two sails

- Cutter - one mast, three or more sails

1. Gaff Cat

2. Gaff Sloop

Two-masted rigs

Two-masted boats can have an extra mast in front or behind the main mast. Behind (aft of) the main mast is called a mizzen mast . In front of the main mast is called a foremast .

The 5 most common two-masted rigs are:

- Lugger - two masts (mizzen), with lugsail (cross between gaff rig and lateen rig) on both masts

- Yawl - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast much taller than mizzen. Mizzen without mainsail.

- Ketch - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller mizzen. Mizzen has mainsail.

- Schooner - two masts (foremast), generally gaff rig on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller foremast. Sometimes build with three masts, up to seven in the age of sail.

- Brig - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Main mast carries small lateen rigged sail.

4. Schooner

5. Brigantine

This article is part 1 of a series about sails and rig types If you want to read on and learn to identify any sail plans and rig type, we've found a series of questions that will help you do that quickly. Read all about recognizing rig types

Related Questions

What is the difference between a gennaker & spinnaker? Typically, a gennaker is smaller than a spinnaker. Unlike a spinnaker, a gennaker isn't symmetric. It's asymmetric like a genoa. It is however rigged like a spinnaker; it's not attached to the forestay (like a jib or a genoa). It's a downwind sail, and a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker (hence the name).

What is a Yankee sail? A Yankee sail is a jib with a high-cut clew of about 3' above the boom. A higher-clewed jib is good for reaching and is better in high waves, preventing the waves crash into the jibs foot. Yankee jibs are mostly used on traditional sailboats.

How much does a sail weigh? Sails weigh anywhere between 4.5-155 lbs (2-70 kg). The reason is that weight goes up exponentially with size. Small boats carry smaller sails (100 sq. ft.) made from thinner cloth (3.5 oz). Large racing yachts can carry sails of up to 400 sq. ft., made from heavy fabric (14 oz), totaling at 155 lbs (70 kg).

What's the difference between a headsail and a staysail? The headsail is the most forward of the staysails. A boat can only have one headsail, but it can have multiple staysails. Every staysail is attached to a forward running stay. However, not every staysail is located at the bow. A stay can run from the mizzen mast to the main mast as well.

What is a mizzenmast? A mizzenmast is the mast aft of the main mast (behind; at the stern) in a two or three-masted sailing rig. The mizzenmast is shorter than the main mast. It may carry a mainsail, for example with a ketch or lugger. It sometimes doesn't carry a mainsail, for example with a yawl, allowing it to be much shorter.

Special thanks to the following people for letting me use their quality photos: Bill Abbott - True Spinnaker with pole - CC BY-SA 2.0 lotsemann - Volvo Ocean Race Alvimedica and the Code Zero versus SCA and the J1 - CC BY-SA 2.0 Lisa Bat - US Naval Academy Trysail and Storm Jib dry fit - CC BY-SA 2.0 Mike Powell - White gaff cat - CC BY-SA 2.0 Anne Burgess - Lugger The Reaper at Scottish Traditional Boat Festival

Hi, I stumbled upon your page and couldn’t help but notice some mistakes in your description of spinnakers and gennakers. First of all, in the main photo on top of this page the small yacht is sailing a spinnaker, not a gennaker. If you look closely you can see the spinnaker pole standing on the mast, visible between the main and headsail. Further down, the discription of the picture with the two German dinghies is incorrect. They are sailing spinnakers, on a spinnaker pole. In the farthest boat, you can see a small piece of the pole. If needed I can give you the details on the difference between gennakers and spinnakers correctly?

Hi Shawn, I am living in Utrecht I have an old gulf 32 and I am sailing in merkmeer I find your articles very helpful Thanks

Thank you for helping me under stand all the sails there names and what there functions were and how to use them. I am planning to build a trimaran 30’ what would be the best sails to have I plan to be coastal sailing with it. Thank you

Hey Comrade!

Well done with your master piece blogging. Just a small feedback. “The jib gives control over the bow of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship.” Can you please first tell the different part of a sail boat earlier and then talk about bow and stern later in the paragraph. A reader has no clue on the newly introduced terms. It helps to keep laser focused and not forget main concepts.

Shawn, I am currently reading How to sail around the World” by Hal Roth. Yes, I want to sail around the world. His book is truly grounded in real world experience but like a lot of very knowledgable people discussing their area of expertise, Hal uses a lot of terms that I probably should have known but didn’t, until now. I am now off to read your second article. Thank You for this very enlightening article on Sail types and their uses.

Shawn Buckles

HI CVB, that’s a cool plan. Thanks, I really love to hear that. I’m happy that it was helpful to you and I hope you are of to a great start for your new adventure!

Hi GOWTHAM, thanks for the tip, I sometimes forget I haven’t specified the new term. I’ve added it to the article.

Nice article and video; however, you’re mixing up the spinnaker and the gennaker.

A started out with a question. What distinguishes a brig from a schooner? Which in turn led to follow-up questions: I know there are Bermuda rigs and Latin rig, are there more? Which in turn led to further questions, and further, and further… This site answers them all. Wonderful work. Thank you.

Great post and video! One thing was I was surprised how little you mentioned the Ketch here and not at all in the video or chart, and your sample image is a large ship with many sails. Some may think Ketch’s are uncommon, old fashioned or only for large boats. Actually Ketch’s are quite common for cruisers and live-aboards, especially since they often result in a center cockpit layout which makes for a very nice aft stateroom inside. These are almost exclusively the boats we are looking at, so I was surprised you glossed over them.

Love the article and am finding it quite informative.

While I know it may seem obvious to 99% of your readers, I wish you had defined the terms “upwind” and “downwind.” I’m in the 1% that isn’t sure which one means “with the wind” (or in the direction the wind is blowing) and which one means “against the wind” (or opposite to the way the wind is blowing.)

paul adriaan kleimeer

like in all fields of syntax and terminology the terms are colouual meaning local and then spead as the technology spread so an history lesson gives a floral bouque its colour and in the case of notical terms span culture and history adds an detail that bring reverence to the study simply more memorable.

Hi, I have a small yacht sail which was left in my lock-up over 30 years ago I basically know nothing about sails and wondered if you could spread any light as to the make and use of said sail. Someone said it was probably originally from a Wayfayer wooden yacht but wasn’t sure. Any info would be must appreciated and indeed if would be of any use to your followers? I can provide pics but don’t see how to include them at present

kind regards

Leave a comment

You may also like, 17 sailboat types explained: how to recognize them.

Ever wondered what type of sailboat you're looking at? Identifying sailboats isn't hard, you just have to know what to look for. In this article, I'll help you.

How Much Sailboats Cost On Average (380+ Prices Compared)

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Sail Dimensions

What Sail Dimensions are Required to Calculate Sail Areas?

The required sail dimensions for calculating the area of any triangular sails are usually its height and the length of its foot. But that only works for mainsails and mizzens with no roach, and jibs with a 90 degree angle at the clew - and what about high-cut headsails, spinakers and cruising chutes? Read on...

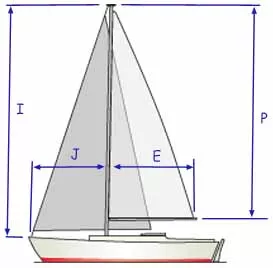

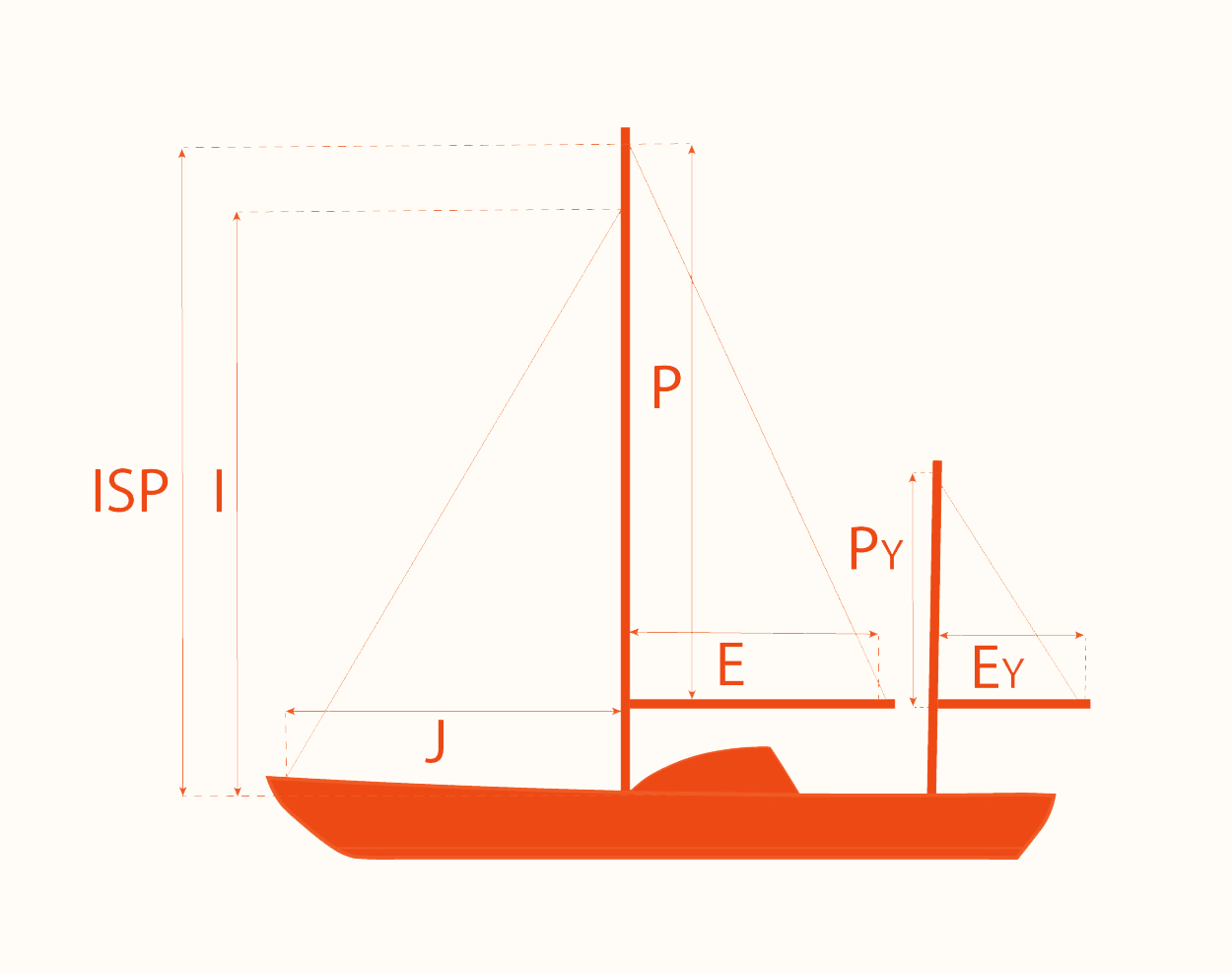

Foresail and mainsail dimensions are universally referenced with the letters 'J', 'I', 'E' and 'P' approximating to the length of the foredeck, height of the mast, length of the boom and the height of the main sail - but more accurately defined further down this page.

Yacht designers need these sail dimensions to calculate thought provoking stuff such as the sail-area/displacement ratios of their creations, and sailmakers need them before they put scissors to sailcloth.

If our sailboat's sails were perfectly triangular then, as every schoolboy knows, their area would be 'half the height, times the base' - but with the possible exception of a mainsail with a straight luff, generally they're not. Here's how it works...

Main and Mizzen Sail Dimensions

These are almost right-angled triangles except for the curvature of the leach (the 'roach') which increases the sail area.

It's usually calculated as:~

Area = (luff x foot)/1.8, or

Area = ( P x E )/1.8, where:~

- 'P' is the distance along the aft face of the mast from the top of the boom to the highest point that the mainsail can be hoisted, and

- 'E' is the distance along the boom from the aft face of the mast to the outermost point on the boom to which the main can be pulled.

For the mizzen sails on ketches and yawls , 'P' and 'E' relate to the mizzen mast and boom.

For more heavily roached sails, the increased area can be accounted for by reducing the denominator in the formula to 1.6.

Clearly calculating sail areas isn't going to be an exact science...

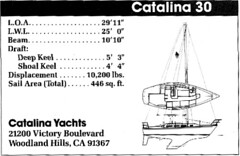

Jibs, Genoas and Staysail Dimensions

For a working jib that fills the fore triangle - but no more - and with a foot that's parallel to the deck, then you've got a 'proper' right-angled triangular sail, whose area is:~

Area = (luff x foot)/2, or

Area = ( I x J )/2, where:~

- 'I' is the distance down the front of mast from the genoa halyard to the level of the main deck, and

- 'J' is the distance along the deck from the headstay pin to the front of the mast.

Genoas, by definition, have a clew which extends past the mast and are described by the amount by which they do so. For instance a 135% genoa has a foot 35% longer than 'J' and a 155% genoa 55% longer. Areas are calculated as follows:~

Area (135% genoa) = (1.44 x I x J )/2, and

Area (155% genoa) = (1.65 x I x J )/2

High-cut Headsails

But these formulae don't work for a high-cut jib with a raised clew - unless you imagine the sail turned on its side such that the luff is the base and the luff perpendicular is the height.

It's still a simple calculation though, once you know the length of the luff perpendicular ( LP ), the sail area is:~

Area = (luff x luff perpendicular)/2, or

Area = ( L x LP )/2, where:~

- 'L' is the distance along the forestay from the headstay pin to the front of the mast, and

- 'LP' is the shortest distance between the clew and the luff of the genoa.

Spinnaker Sail Dimensions

Much like calculating foresail areas, but with different multipliers for conventional spinnakers and asymmetric spinnakers...

Conventional Spinnakers

Area = (0.9 x luff x foot), or

Area = (0.9 x I x J ), where:~

- 'I' is the distance from the highest spinnaker halyard to the deck, and

- 'J' is the length of the spinnaker pole.

Asymmetric Spinnakers

Area = (0.8 x luff x foot), or

Area = (0.8 x I x J ), where:~

- 'I' is the distance from the highest spinnaker halyard to the deck, and

- 'J' is the distance from the front face of the mast to the attachment block for the tackline.

More about Sails...

Are Molded and Laminate Sails One Step Too Far for Cruising Sailors?

Although woven sails are the popular choice of most cruising sailors, laminate sails and molded sails are the way to go for top performance. But how long can you expect them to last?

Is Carrying Storm Sails on Your Cruising Boat Really Necessary?

It's good insurance to have storm sails available in your sail locker if you are going offshore, and these are recommended fabric weights and dimensions for the storm jib and trysail

Using Spinnaker Sails for Cruising without the Drama!

When the wind moves aft and the lightweight genoa collapses, you need one of the spinnaker sails. But which one; conventional or asymmetric? Star cut, radial head or tri-radial?

The Mainsail on a Sailboat Is a Powerful Beast and Must Be Controlled

Learn how to hoist the mainsail, jibe it, tack it, trim it, reef it and control it with the main halyard, the outhaul, the mainsheet and the kicker.

Is Dacron Sail Cloth Good Enough for Your Standard Cruising Sails?

Whilst Dacron sail cloth is the least expensive woven fabric for standard cruising sails, do the superior qualities of the more hi-tech fabrics represent better value for money?

Recent Articles

The CSY 44 Mid-Cockpit Sailboat

Sep 15, 24 08:18 AM

Hallberg-Rassy 41 Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 14, 24 03:41 AM

Amel Kirk 36 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 07, 24 03:38 PM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

Dave Dellenbaugh Sailing

David Dellenbaugh is a champion helmsman, tactician, author, coach, rules expert and seminar leader who has spent his career helping sailors sail faster and smarter.Here are the learning resources that he has created to help you improve your racing skills.

- The FAST Course

Jib and Genoa Trim

The jib and genoa are very important because they provide most of the driving force for your boat. There are two reasons for this: First, your headsail has no mast in front of it to create turbulence and spoil clean flow. Second, it sails in a continual lift caused by the main's upwash.

Upwash is the bend that a sail induces in the approaching air flow. For example, the wind begins to curve around a mainsail well before it actually touches the sail. Sitting in this upwash region, the genoa thinks it is in a lift, and consequently can be trimmed farther off the centerline of the boat than the main. This makes the genoa more efficient by rotating its forces (perpendicular to the chord line) more forward and less sideways than the main.

If your main is the sailplan's rudder, then the genoa is its motor. Of course, their functions overlap, but in general you should trim your genoa for drive and your main for helm balance.

Describing a genoa

The most obvious characteristics of a genoa are its size and shape. We measure genoas by the length of their LP, or luff perpendicular. To construct an LP, draw a line from the sail's clew to its luff, intersecting the luff at a right angle. The length of the LP divided by J (the distance from the forestay to the front of the mast) equals the overlap of the sail.

LP divided by J = Overlap (%)

On IOR boats, the largest headsails usually have a 150% overlap; No. 2s have a 130% overlap; No. 3s have a 98% overlap, and so on. Most PHRF boats are allowed 155% genoas without penalty.

The sails that are less than maximum size are used in heavier winds once the maximum amount of force for a given boat has been reached. Beyond this point, maximum sail area simply overburdens the boat, and it's better to reduce drag by changing down to a smaller jib. This will improve the lift-to-drag ratio (the best indicator of upwind performance) by holding lift at a minimum while lowering drag.

Note that smaller headsails are almost always shorter on the foot, but still nearly full hoist. The reason for this is that a high-aspect-ratio sail is more efficient. The sailmaker preserves the maximum wingspan of the boat's foils, but shortenis their width to the limits of construction technology.

Genoa Trimming Procedure

Like the mainsail trimmer, the person who tends the genoa needs a methodical approach to cover all variables and maintain fast shapes. Here is a trimming procedure that you can use when you set up your genoa. The six basic steps are:

- Determine overall power by selecting the correct genoa.

- Determine the efficiency of the genoa with the lead angle.

- Set depth and twist with sheet tension.

- Set depth and twist with the fore-and-aft lead position.

- Set depth and twist with backstay tension.

- Set draft position with halyard tension.

Step 1: Determine Overall Power by Selecting the Correct Sail

This first step isn't too tough if you sail in a one-design class that allows only one jib, but it can be perplexing on big boats with up to 14 headsails. The best way to make good sail selection choices is to keep a record of the headsails you use with wind velocities and boat performance. After a while you'll have an extensive chart as a guide.